In the Unconventional City Planners series, Mackenna Caughron explores three unconventional planners and their machinations of the city. This is the final part of the 3 part series.

Disney’s foray into the tangible – Walt Disney World – has been lauded as the “most imaginative piece of urban planning in America” (though the California’s Disney Land is the only amusement park that Walt Disney lived to see open, Florida’s Disney World opened 5 years after his death).

Disney’s prowess in the surreal is undeniable. Disney’s sugary sweet fantastical Americana shakes Disney visitors into a nostalgic glow, one that demands a price of over $550 per day for a family of four (before hotels, flights, confectionary treats, Fast Passes, and souvenir glitter Minnie Mouse ears).

Not surprisingly, Disney yearned to build a “real” world as well. He briefly and incompletely planned the construction of an actual city, one where visitors were not expected to wear character paraphernalia.

What happens when the dreamer meets reality? Seven Arts City. What began as an ambitious partnership with California Institute of the Arts, the Seven Arts City sought – like its brother fantasy theme parks – to inspire. Though the real world prevented the city from taking flight.

Location of Seven Arts City

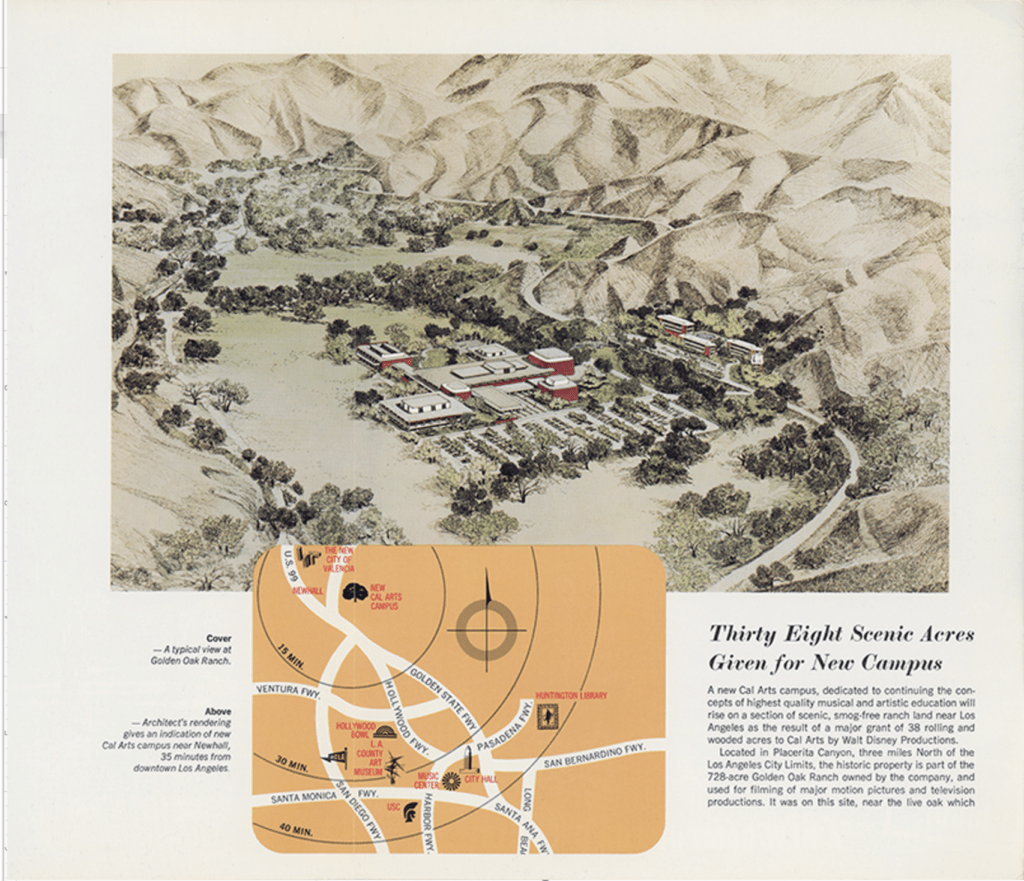

Where else would a real Disney-city be other than California? Even more fitting, the site acted as a famed backdrop of several Disney films. The bucolic Golden Oaks Ranch sits a 30 minutes (no traffic) drive from Los Angeles’ downtown core, in Santa Clarita, California.

Its commercial history began in 1842 as the site of California’s first gold strike (though this is somewhat contested, as myths often are – it still made its way into the promotional brochure for Seven Arts City).

The Santa Clarita location was carefully chosen for its “beauty, accessibility, and growth potential“.

It was in this bucolic setting of Hollywood’s old wild West, where Walt Disney dreamt of an arts mecca for the everyday person.

Urban Experience

Despite its ambition to become a global attraction, Seven Arts City would not solely entertain. The merger of the Chouinard Art Institute and Los Angeles Conservatory of Music (“CalArts”) emboldened its design – why not create a dual-purpose campus, creative center, and…. destination (I mean, it is Disney, after all, he had to find a profit-inducing angle).

Unlike Disney’s parks, Seven Arts City would house a hivemind of 1,200 students representing diverse artistic skill sets – film, music, paint, dance, fashion, sculpture, theater – all working together on experimental projects that would push against convention. Residences would sit in suburb-like rows, next door to the central hub within comfortable walking distance.

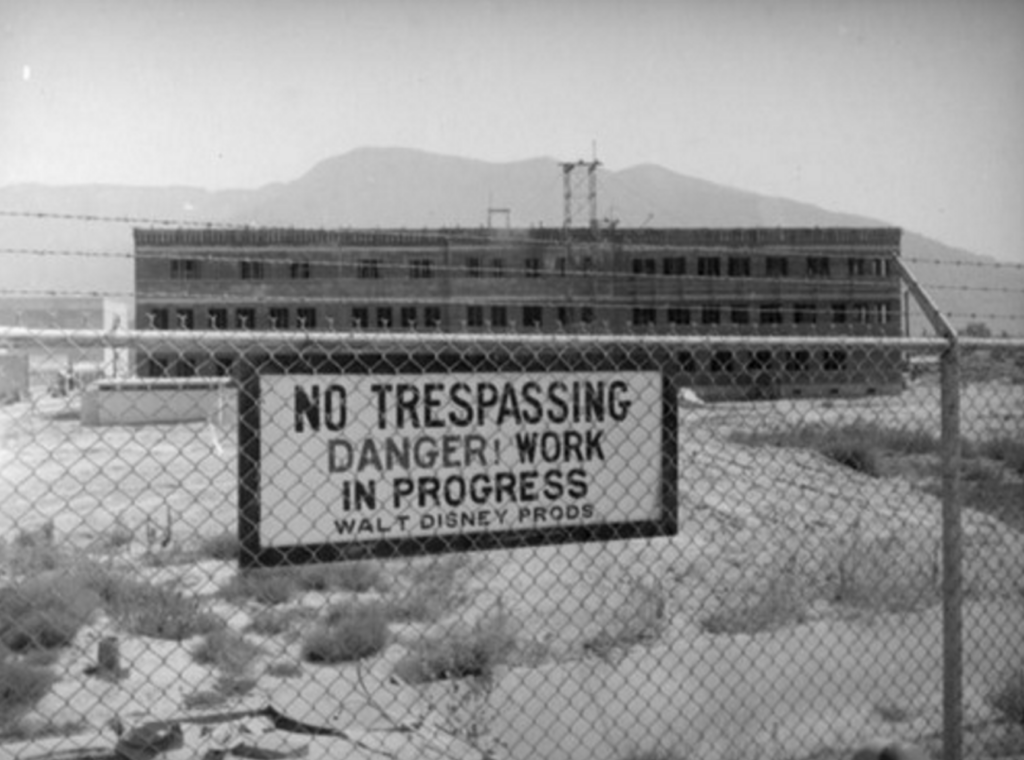

Though Golden Oaks Ranch consisted of 700+ acres at the time of the city’s planning, only a subsection – 38 acres – were deeded to CalArts. Roughly the size of Central Park’s Ramble, the Seven Arts City would feel cozy, familial, and right-sized – just like a Disney theme park. Its internal veins would be foot-traffic friendly, though the city would remain accessible via the newly completed San Diego, Antelope Valley, and Foothill freeways, serving California’s car-owning population.

Challenges

One year after its big promotional push, Seven Arts City lost its visionary “John Hammond” when Disney died suddenly. Without its crucial financial and starry-eyed supporter, the project shifted from its original grandiosity.

Details remain murky on the specifics of Disney’s intended artistic paradise. Wolf Burchard, museum curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art acknowledged, “No visual material [exists to] illustrate what [Seven Arts City] would have looked like…”

The drawings in promotional materials remain artistic and lack needed clarity. Disney – especially as he progressed in his career – operated at a distance from the details. Without his oversight, the plan fizzled. Even the Golden Oaks Ranch site eventually proved unstable due to unforeseen geological forces.

The idea of Seven Arts City became the eventual permanent campus of CalArts in Valencia. Particulars of the original plan persisted, including a main building as the central organ and an academic ideology of interwoven arts. Most importantly, the CalArts institution carries on, and remains to this day a fine choice for burgeoning arts students.

Though the grandeur of a mecca, one for the artist and art-curious alike, faded.

What do we take away?

Both in form and feel, Seven Arts City would be the functional embodiment of “gesamtkunstwerk“, a concept coined by composer Richard Wagner. The term criticized the slicing of the opera, but later inspired a movement to unify all arts (gesamtkunstwerk translating to “total arts”). As has been astutely observed, Disney mirrored the union of arts in his famed medium: animation, music, and film. But he also sought it in his tactical experiences.

Disney at the helm of the city still had a creator’s eye. Undeterred with the details, he was still watching one aspect of the creative process. As Robin Allan described in his biography of Disney, though he “became increasingly uninvolved in the actual animation work, his contribution extended from what his employees described as his consummate ‘storytelling’…”

Disney loved the awe of an arc. So much so, he templatized his process (and many others have documented his winning formula). Seven Arts City was no exception. Disney promoted the powerful narrative of an experimental, innovative center in the backdrop of northern Los Angeles. And everyone bought a ticket.

More compelling, the decision to market the idea as a destination for students and visitors alike brings both population segments to the city. Students wishing to share experimental work will benefit from visitors wishing to see world-class visual stimuli. The awe, inspiration, and excitement feels familiar. Maybe like how one feels at Disney World?

Disney – consciously or not – idealized Seven Arts City with respect to sensory stimuli and emotional states. And this effort is consistent with his overarching career. Journalism scholar Josef Chytry argued that “Disney’s objectives should be seen largely with regard to certain specific emotional results – optimism, contentment, excitement, happiness…” He attaches his work to feeling.

Disney (now as a company, formerly the person) creates these “emotional environments” in film, parks, and products. Childhood wonder and curiosity are promulgated without term limits. Where Akon City and Starbase fill a gap or address a problem (economic disenfranchisement in Africa and Earthly climate instability, respectively), Disney seeks to evoke feeling as a primary outcome. But note, all of our unconventional planners look to blank canvases to design their dreams. No one is interested in bending our current predicaments toward progress.

Planners rarely are afforded the luxury of dealing in the surreal. Most inherit existing infrastructure, residents, economic pitfalls, and barriers to development. Though there are lessons in each of the unconventional planners.

Akon City sought to nourish.

Starbase sought to give foundation.

Seven Arts City sought laughter.

And all of these objectives are worthy pursuits of our city, however frivolous and problematic. So when we plan our cities, we should do so with unconventional planners in mind. While flawed at times in execution, they reach. They inspire. And when our cities cease to dream, so do its residents.