The social housing movement has been on the rise in the United States, and particularly since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the inequity tenants face in trying economic times. Over the coming months, I will be delving into tenant and social housing movements across America in order to better understand both the overarching themes in the nation’s housing movement and, even more importantly, the complexities and differences that come with each city and region. The first city I will analyze is my hometown of Philadelphia, PA.

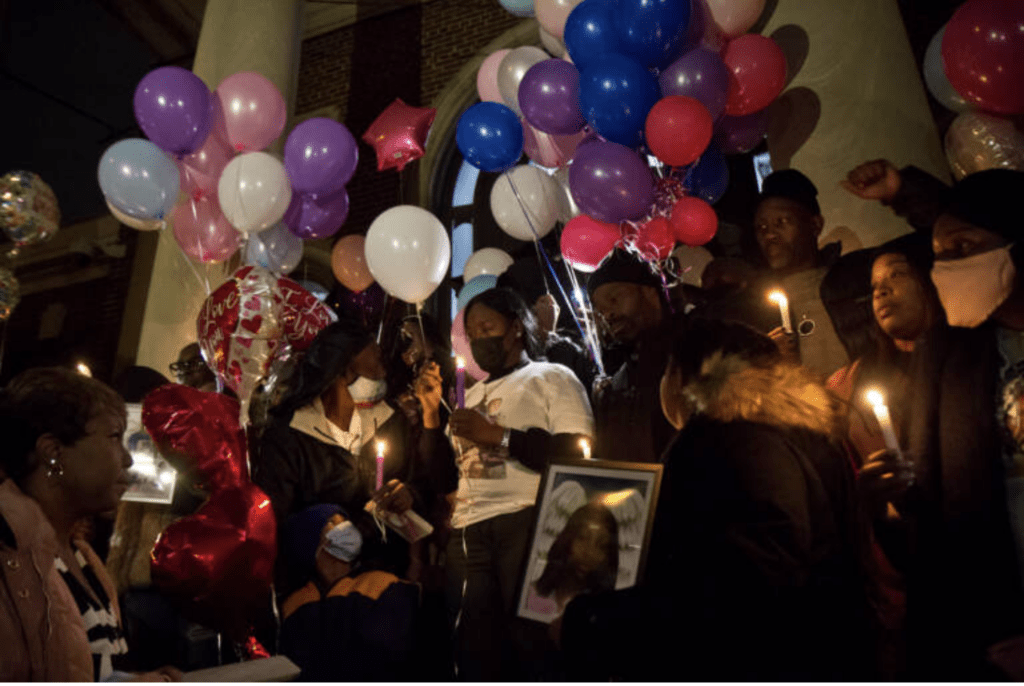

On January 6, 2022, 12 people were killed in a house-fire on 23rd and Fairmount. The building was owned by Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA), the bureaucratic organization providing public housing for thousands of Philadephians. The multi-generational family living in the house was overcrowded; and as of 2016 they were placed on a waiting-list to be placed in a more accommodating residence. Furthermore, the house lacked battery-powered smoke alarms, sprinkler systems, and fire extinguishers, all of which are now common in more up-to-date public housing units in Philadelphia.

These events sparked outrage from tenant organizations, housing advocates, and particularly, residents of PHA-owned housing . How could the city not have placed the family in a more accommodating home sooner? Why was the family’s home not adequately kept up the proper safety precautions? Officials in Philadelphia cite the lack of funding from the United States Department of Housing and Development (HUD), which has seen PHA’s budget cut drastically over time. However, to the citizens of Philadelphia, this explanation is simply not proactive enough. Families dying in preventable fires is unacceptable, and aid to ensure such tragedies never occur again is vital to the city’s residents.

I find, in order to best understand the growing tensions amongst the residents of Philadelphia and the PHA, it is necessary to unpack the housing vacancy crisis in North and West Philadelphia and the eventual “Occupy PHA” movement of 2020.

As of 2018, there are nearly 12,000 vacant homes in Philadelphia, which is the third-highest total in the United States, behind Baltimore, MD and Detroit, MI. Those homes are included in the estimated 42,000 vacant properties across the city, which range from livable dwellings to vacant lots. These numbers begin to hold relevance for the citizens of Philadelphia when one analyzes the rate of homelessness in the city. As of 2020, the Office of Homeless Services of the City of Philadelphia estimates that nearly 6,000 people across the city experience some form of homelessness with nearly 1,000 of which are unsheltered.

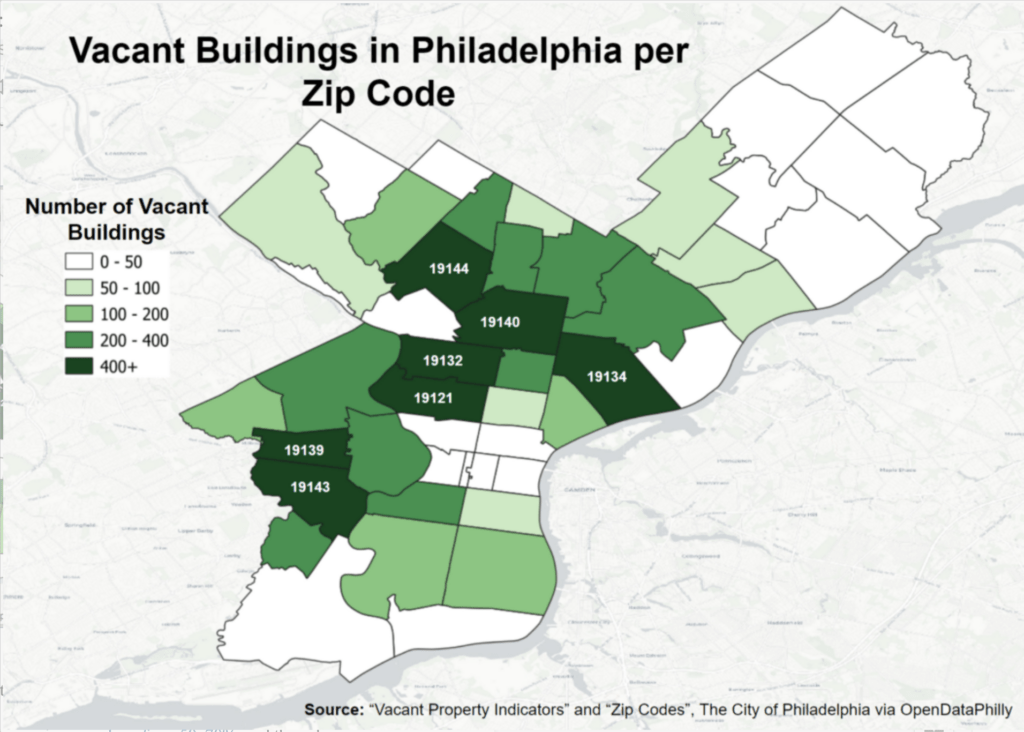

Using the Vacant Property Indicators dataset from the City of Philadelphia via OpenDataPhilly, which has been consistently updated since in 2016, the locations of the vacant buildings across Philadelphia can be mapped out through GIS mapping software, which is displayed below:

The areas suffering the most from vacant buildings are labeled with corresponding zip codes, and are mostly made up of neighborhoods in North and West Philadelphia. Neighborhoods in these areas of the city are predominantly Black, ranging anywhere from 50–70%, and they also experience significantly higher poverty rates compared to the rest of Philadelphia. For example, Nicetown-Tioga, which is located in ZIP 19140, has a median income of $17,493 as of 2018.

The juxtaposition of dwelling vacancies and the homelessness rate has caused major protests in Philadelphia, most notably the Ben Franklin Parkway encampment for homelessness advocacy, which lasted almost three months during the Summer of 2020. The protestors created an encampment that blocked transportation on the Ben Franklin Parkway in the hopes to discuss the abundance of vacant, abandoned homes across the city, particularly in North and West Philadelphia with city officials and the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA), which is the largest landlord in the entire state as it currently operates over 14,000 affordable homes in the city. Their main demands were to acquire livable homes, which they believed that PHA hoarded in large numbers from the homeless population of the city in order to sell them to privately owned developers to create affordable housing that often was not affordable to those needing PHA sponsored, social housing.

Philadelphia Housing Authority owns over 13,400 vacant units, which are split up into two categories: PHA-owned properties and Tax Credit Properties. The latter of which are operated by non-profit organizations aimed at providing affordable housing units to low-income citizens in Philadelphia. The PHA is often criticized for delaying the selling of properties to those in need of housing, particularly low-income and homeless citizens, which they refute by stating that HUD delays the process for months if not years.

Jennifer Bennetch, leader of the Occupy PHA movement, pointed out that many single mothers with children attempted to find a place to live and upkeep the infrastructure, but were at risk of the PHA evicting them with the use of police force. This has been another major critique of the PHA as a significant portion of their funding has gone to their police unit that evicts ‘squatters’ in vacant units across Philadelphia. Furthermore, Bennetch referenced the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Philadelphia, mainly that shelters limited their capacity so that social distancing requirements would be met. Due to the pandemic, far more families that depended on shelters for daily use were now on the streets, especially across North Philadelphia. The homes owned and operated by PHA to many homeless citizens in the city are last ditch efforts in an attempt to receive needed shelter, particularly during a public health crisis such as the pandemic has brought upon the United States.

After three months, the Occupy PHA were awarded 48 PHA owned units in exchange for the demonstration to end peacefully. The houses were transferred to the newly created Philadelphia Community Land Trust in order to ensure a proper legal transition.

Unfortunately, in February of 2022, Jennifer Bennetch passed away at the age of 36 due to complications of COVID-19. Her activism in Occupy PHA led to the creation of the Philadelphia Community Land Trust, housing those same families that fought alongside Jennifer.

The achievements of Occupy PHA in 2020 were substantial for the city of Philadelphia and the entire housing movement in the United States; however, it is evident from the fires in January of 2022 that there is much work to be done. Nevertheless, it is important that activists’ voices across the city continue to be amplified and tenant protections passed in order to further the mission that people such as Jennifer Bennetch have set out for the people of Philadelphia.