In last December’s mad dash to sew up some last minute accomplishments before leaving office, former New York Mayor Bill de Blasio and former Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) Commissioner Henry Gutman released the NYC Streets Plan. The 96-page document positively outlines the accomplishments of the de Blasio administration’s, particularly relating to Vision Zero, and sets a good framework for the new mayor Eric L. Adams to follow as he and his NYCDOT Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez chart a course for the city’s streets.

Here are some key elements of the plan:

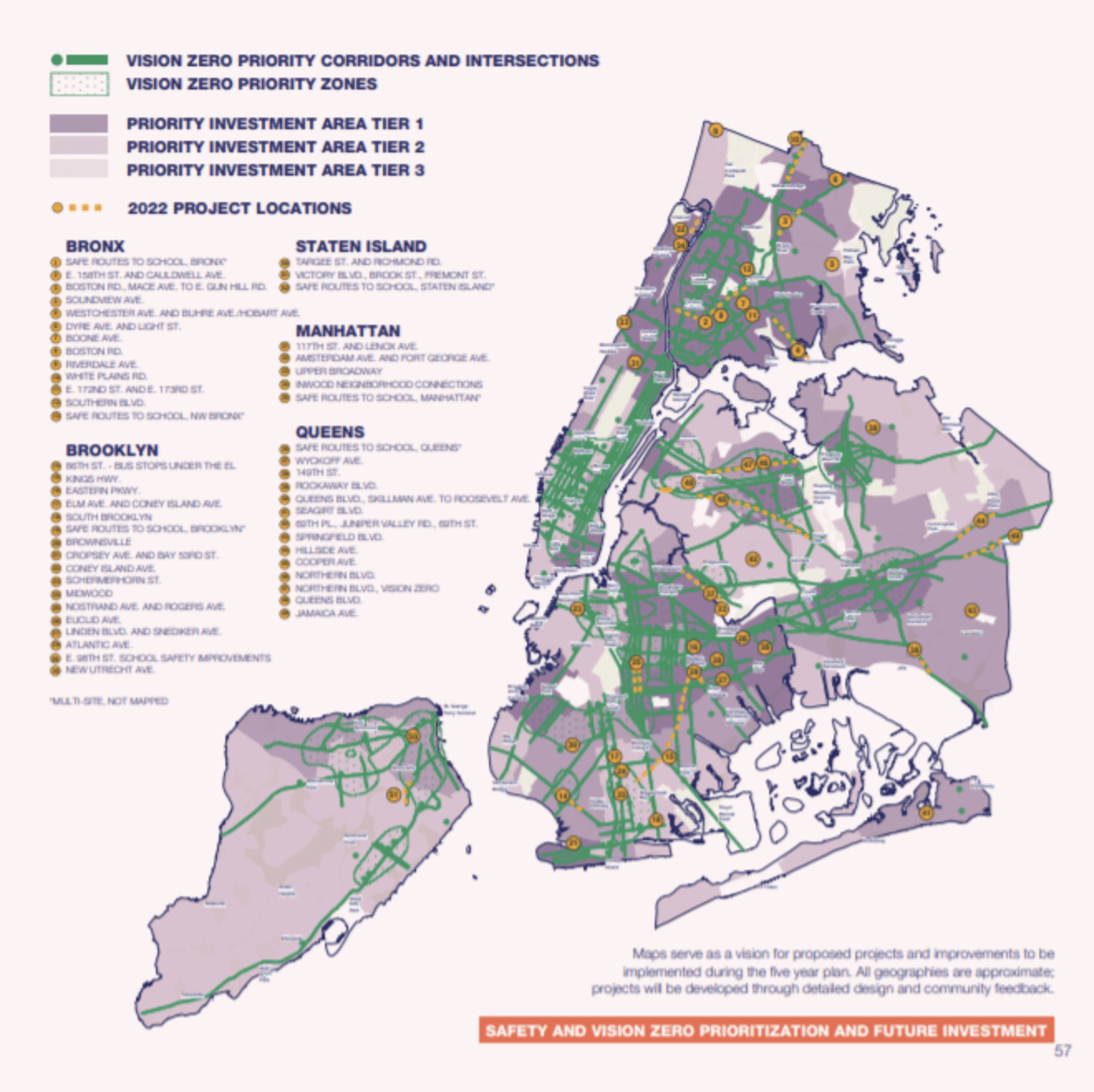

The plan aims to expand the Vision Zero safety improvements in an equitable way.

The Vision Zero initiatives outlined by the plan include expansion of Priority Corridors and Intersections, School Safety Areas and Senior Pedestrian Zones (see end of article for expanded definitions).

The plan also calls for expanding the OneNYC Great Streets program, which facilitated safety and streetscape upgrades along such major thoroughfares as Queens Boulevard and the Bronx’s Grand Concourse.

On an equity basis, Vision Zero has clearly neglected some communities, including some that the City has identified as being prioritized for more investment. Many of these communities are in Southeast Queens, which presently has no Vision Zero Priority Corridors, despite relatively high crash counts along the busy commercial corridors of Linden, Springfield, and Merrick Boulevards.

Lastly, the plan calls for a “dramatic” expansion in automated traffic enforcement to combat illegal turns, parking and use of bike lanes and loading zones. Automation would promise much more robust enforcement of things like bike lane parking, which is hardly enforced in New York at all, it seems. Better enforcement in these areas would enhance street safety for all street users – drivers, pedestrians and cyclists alike.

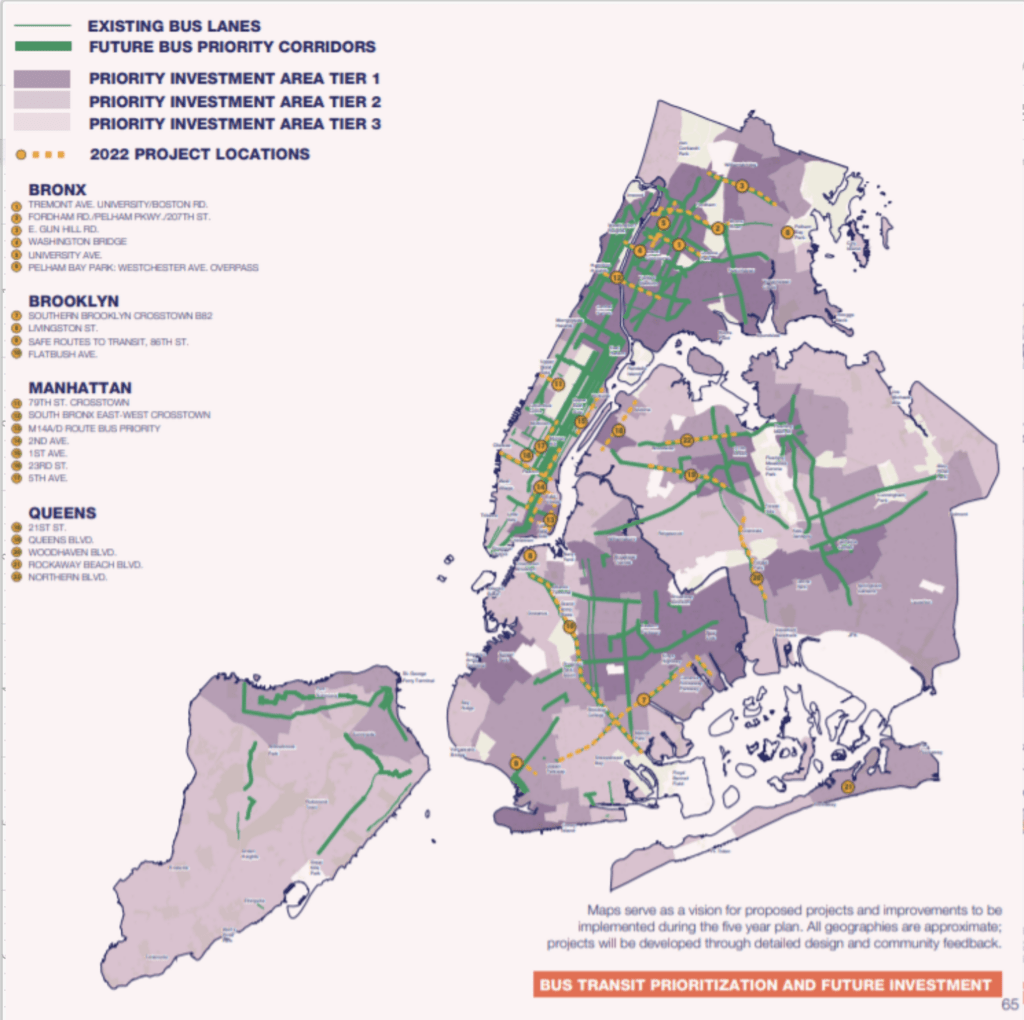

The plan promises major improvements to bus infrastructure.

The plan calls for the City to build on the success of such projects as the 14th Street Busway in Manhattan, which improved travel time along the crosstown corridor by 24 percent.

The plan delineates a number of so-called Bus Priority Corridors in all five boroughs, including Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, Queens Boulevard and Brooklyn’s Utica Avenue. Along these corridors, the plan recommends significant capital improvements, including transit signal priority, bus stop amenities like shelters and countdown clocks, and, yes, busways.

The plan does not identify any specific locations for any specific capital improvements, apart from the in-the-works-for-a-long-time Fifth Avenue Busway. The plan could do with more specifics and more goal-setting, especially since there are bus corridors begging for this treatment, like Manhattan’s 34th Street and the Bronx’s Southern Boulevard.

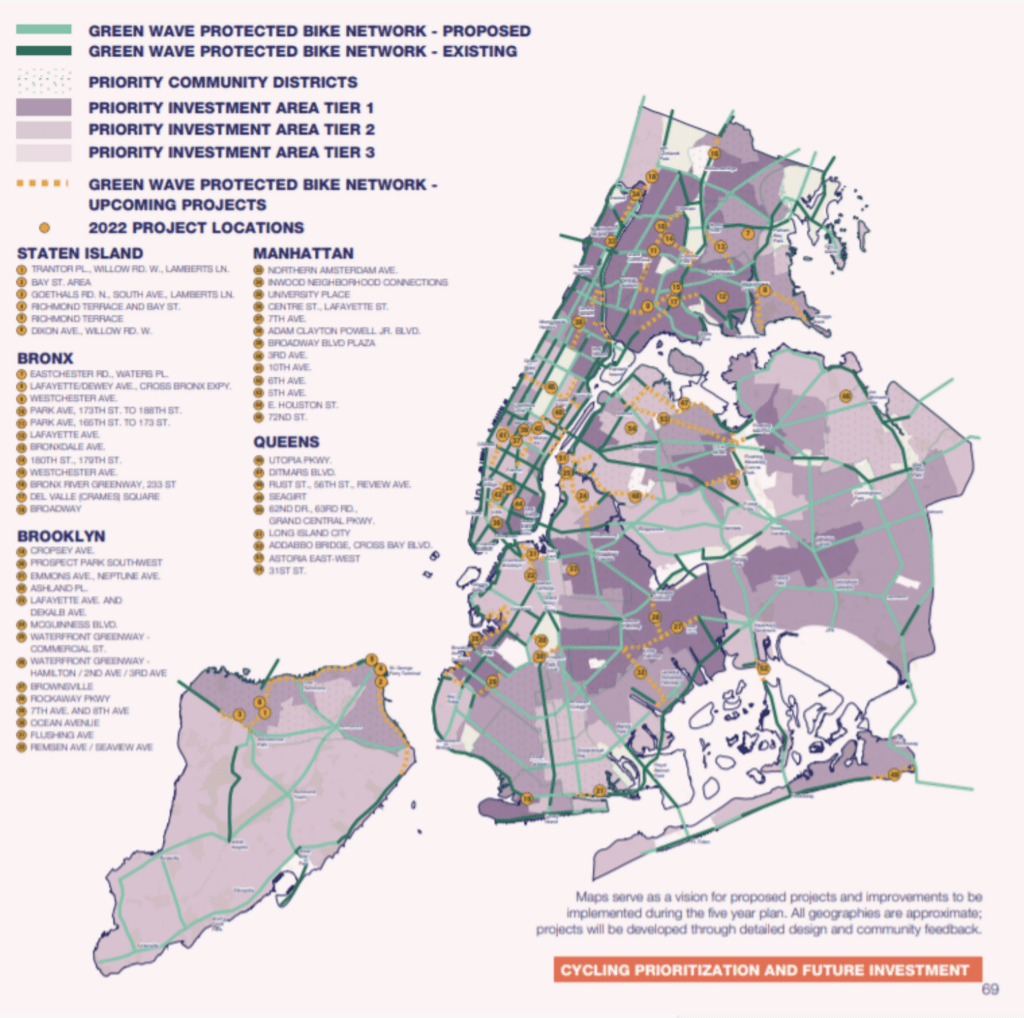

The plan aims too low on bikes.

The Streets Plan promises to build out the bike network shown in the Green Wave plan, which was published in 2019 – before New York’s pandemic-induced bike boom. The Green Wave plan was good, but could be better. And since the two years since that plan’s publication have been transformative in regard to cycling demand in New York, the updated Streets Plan ought to have been transformative too.

Included in the plan is the promise of 10,000 new on-street bike racks, while promising to “explore” weather-protected alternatives like Oonee pod, which has already been rolled out at Grand Central Terminal, as covered by my colleague Ben Listman.

On CitiBike, the plan holds steady and calls for the continued rollout of the system’s phase 3 expansion, which has brought the service as far north as Kingsbridge, Bronx, as far south as Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and will bring it as far east as Corona, Queens by next year.

This expansion will be all done with private sector funds. If the City is serious about this, as it should be, it should put its money where its mouth is and make a serious investment in expanding CitiBike deeper into the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, quicker. This investment would help the City meet its equity goals and work toward eliminating the several transit deserts in these boroughs, which are almost all left unserved by CitiBike.

The Streets Plan’s bike prescriptions were good for 2019, but not for the post-pandemic, post-bike boom version of New York.

——

The NYCDOT Streets Plan provides a loose framework for continued, incremental improvement to New York City’s transportation infrastructure. For those looking for revolutionary change, the plan falls well short.

Mayor Adams and Commissioner Rodriguez should consider this document a good baseline against which to judge their transportation accomplishments. Following the plan would represent an almost linear continuation of the progress made under Mayor de Blasio. Anything less than what’s in this plan would likely count as a major failure for the new administration. Anything more, a major success.

- Priority corridors refer to those corridors with a higher pedestrian KSI (killed or seriously injured) per mile rate than the median in a given borough.

- Priority intersections refer to those intersections with a higher pedestrian KSI (killed or seriously injured) rate than the 85th percentile intersection in a given borough.

The NYC Streets Plan outlines crucial initiatives aimed at reshaping urban mobility and enhancing the quality of life for New Yorkers. Three key takeaways emerge from this comprehensive plan. Firstly, the emphasis on pedestrian-friendly infrastructure signifies a pivotal shift towards prioritizing safety and accessibility. Secondly, the ambitious expansion of bike lanes underscores the city’s commitment to sustainable transportation options. Lastly, the incorporation of community input demonstrates a collaborative approach, ensuring that the plan addresses the unique needs of neighborhoods across the city. Overall, the NYC Streets Plan sets a promising course towards a more inclusive, efficient, and environmentally-conscious urban landscape.