Sun set on 5th Avenue in Brooklyn, on the last day of this year’s Park Slope Open Street program. In the waning light, children ran after bubbles in the street, vendors sold light up toys, dogs sniffed the ground, and restaurant goers, blankets across their laps, sipped beers with gloved hands. Organizers have opened the street (or closed it, depending on your perspective) for over 50 weekend days in 2021: an involved effort demanding long hours, a small platoon of paid staff, and considerable event planning. On the Saturday after Thanksgiving, residents lit a towering Christmas tree next to Washington Park. The following day, the Open Street shut down for the winter.

Since its inception in Spring 2020 to provide open space to socially-distant, virus-wary New Yorkers, the Open Streets Program has had a tumultuous rollout. Mayor de Blasio’s program, which has been called “the nation’s largest” by advocates, aimed to temporarily close up to 100 miles of New York streets to cars in 2021, freeing up public outdoor space for pedestrians, cyclists, and diners.

As it expanded, opponents complained about lost street parking and traffic congestion and, in some cases, took drastic measures to protest the program. Early on, the city abandoned the Prospect Park West Open Street, as residents feared the Open Street diverted traffic down once-quiet side streets. In April, someone disguised as a delivery driver threw Greenpoint’s Open Streets barricades into Newtown Creek. Opponents have also berated volunteers and glued barricade locks so they couldn’t be put out.

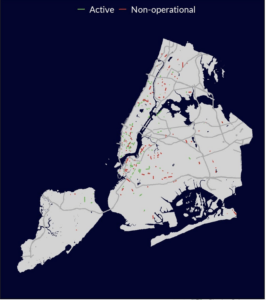

The Open Streets program also fell far short of its goals. According to a summer survey conducted by Transportation Alternatives, only 46 percent of Open Streets were operational, just over 24 miles of the 100 mile goal. In response, the Department of Transportation (DOT), which oversees the program, claimed that, according to internal data, there were 47 miles of active Open Streets, higher than the survey found, but still well short of the 100 mile goal, and a fraction of roughly 80 total miles of listed Open Streets at the time of the report.

Open Streets, while failing to meet its goals, has already shown tremendous benefits. Research says open streets promote physical activity, encourage cycling, walking, and public transportation, strengthen the social fabric of neighborhoods, and improve road safety, with neutral or positive effects on businesses. Advocates tout some additional benefits like repurposing street parking, reducing community policing and traffic enforcement responsibilities, reductions in cyclist and pedestrian traffic injuries, and increases in air quality. The expansion of Open Streets coincided with increased car traffic citywide, as tracked by vehicle crossings across the city’s bridges and tunnels, as well as corresponding rises in traffic deaths and congestion. But while traffic deaths rose elsewhere, traffic accidents declined on Open Streets closed to car traffic, according to Transportation Alternatives’s analysis.

As winter sets in, the fate of New York City’s Open Streets hangs in the balance. Many streets, like the Jennings Street Open Street in the South Bronx, had to shut down before the cold when its summer funding ran out. With such a small share of streets in operation, even during the year’s warmest months, Sara Kaufman, an expert at the Rudin Center for Transportation at NYU, is “concerned” about some Open Streets not reopening.

In Brooklyn, Open Streets Hibernate

Brooklyn has 77 Open Streets, according to the city’s open data portal in early December. This summer, 60 percent of Brooklyn Open Streets were non-operational, according to Transportation Alternatives. That number likely rose as the season changed.

Open Streets relies on volunteers and local community groups, like business improvement districts, schools, nonprofits, and neighbors to run the day-to-day operations like putting out barricades, preventing cars from driving around them, and drawing people to the streets with programming and activities. Volunteers can’t keep up. The city directly supports some Open Streets, by helping set up barricades regularly. But in other communities, they drop off barricades and leave it to volunteers and neighbors to set up barricades according to schedule. “I think volunteers have lost steam” says Kaufman, “And I think without built in programming, people don’t really see it as a place to gather.” In a late November Webinar hosted at NYU, Nicole Gelinas of the Manhattan Institute emphasized the rich history of street programming to bring people to public space, noting constant events at Bryant Park and Herald Square and the city’s Playstreets initiative that began over 100 years ago.

Running Open Streets is a lot of work. Just ask Mark Caserta, Executive Director of the Park Slope Business Improvement District (BID). Park Slope’s 5th Avenue Open Street has been one of the city’s more successful, thanks to the BID, whose full time staff work long hours each Saturday and Sunday alongside two shifts of paid workers to staff barricades, keep streets operating, and prevent cars from coming through. They bring in programming, music, and events. They’ve been harassed, yelled at, and nearly run over protecting their Open Street. “We are trying to change people’s lifestyles,” says Joanna Tallantire, Deputy Director for the BID, “…and the backlash is brutal, people are really cruel to us. That is what the city needs to help us with.”

That lifestyle change asks residents to rethink a car-dependent culture that has long been a feature of New York City and a thorn in the side of transportation advocates who argue for climate-friendly, space-saving transportation substitutes like biking, buses, and subways. Much of the backlash to Open Streets has come from drivers, who frequently move or drive past barricades to access roadways, according to this Open Street user’s own observations and recorded citywide by Transportation Alternatives’s summer study. Inconsistent Open Streets schedules and lack of awareness of program functions and schedules on the part of NYPD traffic enforcement has frustrated both volunteers and drivers.

Most New York residents, however, live in car-free households; and most residents support Open Streets. Citywide, polling has shown broad support for the program, and even greater support for individual Open Streets. Ashley and Lauren, two Park Slope mothers, braved the cold for one last street closure this year to watch the 5th Ave tree lighting with their families. Keeping an eye on their prancing children, they said they’ve been coming to the Open Street since the summer, to visit restaurants they might not have otherwise been able to dine at, get the kids out of the house, listen to live music, and reconnect with their neighbors.

If you walked further South on Fifth Ave this summer, you would have run into another Open Street strip in Sunset Park. Viviana Vizcaino, who lives in the neighborhood, says the closures were “reminiscent of the block parties that used to be common around here, but more frequent and without the cost to us all for permits.” The neighborhood BID played a big role in Sunset Park too. Deciding that staffing barricades was too much to ask of volunteers, the BID raised money on GoFundMe for staff wages, a “pay as you go” model, as the BID’s executive director David Estrada told Brooklyn paper this summer: “If we raise enough money for Saturdays through Oct. 30, we will do that.” They didn’t make it that far, residents reported.

Both beloved 5th Ave Open Streets will hibernate for the Winter. DOT lists weekly hours for Open Street closures on their open data portal, but there’s no information about seasonal closures.

“The Mayor likes to pretend it’s a year round program but for the most part it’s not,” says Caserta. As winter approached, the Park Slope organizers shortened the length of their Open Street depending on demand and weather. The Saturday after Thanksgiving, the Open Street shrunk from 14 blocks to just a few blocks on Fifth Ave by Washington Park. The BID is choosing not to operate the Open Street from December to March, citing lower attendance due to cold weather, early sunset, and staff burnout.

Even with so many Open Streets in jeopardy, De Blasio “doubled-down” on the volunteer approach, despite calls from advocates for DOT to take a more active role in selecting and operating Open Streets. Caserta believes in the program and thinks it can be successful, but acknowledges that Park Slope’s Open Street has thrived, while others have not gotten the chance, because Park Slope has tremendous resources and community buy-in. He thinks the city can do more to help communities implementing the program, like funding for sponsoring organizations, training on how to set up barricades, and improving communication between agencies involved in the program.

Deep Spatial Disparities

Transportation Alternatives found citywide what Caserta observed in Brooklyn. Their survey revealed disparities in where Open Streets were located and which were still in operation, finding a dearth of Open Streets in the city’s poorer neighborhoods with greater proportions of people of color. For example, in the Bronx, 84% of Open Streets were not operating according to surveyors, leaving under one total mile of operational Open Streets in the whole borough.

When even the best-resourced Open Streets run out of programs, money, and person power to run their pedestrian spaces year round, it’s no wonder Open Streets in long-neglected neighborhoods have shut down operations. As the pandemic revealed deep disparities in our city, the inequitable rollout of a pandemic-response program added insult to injury.

Newly-inaugurated Mayor Eric Adams has vowed to address the spatial, race, and income disparities at the heart of implementation so far. At a fall campaign stop, he layed out some criteria for selecting Open Street locations: “We need a real system, a mapping system to show us in real time where the DOT is building to make sure that it’s equitable… we’re going to judge by high illness rates, higher asthma rates, high diabetes rate, high heart disease rate, once we know where the rates are, that is what we should be going first.”

Changing lifestyles requires confronting big, politically-sensitive questions about which public space users the city will prioritize, like pedestrians, cyclists, drivers, and how those users intersect with city neighborhoods segregated by race and income. Adams’s comments suggest that the city may play a more active role in planning Open Streets next year, and new legislation mandates that it must. But when the differences between successful and abandoned Open Streets come down to disparities in community resources, it’s hard to imagine that any program that doesn’t provide significant resources directly to communities will make significant headway on equity issues.

What does “community resources” really mean? Here’s what Park Slope has that other communities may not: first, a business improvement district (BID) with two full time staff; second, money, raised from residents and local small businesses, to pay up to 30 workers and event planning experts to staff barricades and prevent cars from coming through; third, wealthy residents, from whom the BID was able to fundraise tens of thousands of supplemental dollars over a short period of time to support Open Streets; fourth, relationships, in the form of direct contact info for MTA supervisors, city sanitation staff, and local police precinct leadership to coordinate street closings; finally, barricades – Park Slope’s BID purchased 25 additional barricades to supplement their haphazard collection of barriers from DOT and NYPD.

Open Streets have succeeded where sponsoring organizations are equipped to support them. Business Improvement Districts have taken a leading role in innovating public space in New York City. BIDs are well financed and have a granular approach, with their fingers on the pulse of a neighborhood and the needs of business owners. But ultimately, NYC BIDs are almost entirely located in wealthy neighborhoods (they cover just 2% of the city, primarily in Manhattan), and they prioritize private business interests, which are sometimes in conflict with public use.

Other Open Streets have found success not with deep pockets, but with deep community buy-in and countless volunteers, like 34th Avenue in Queens, Greenpoint in North Brooklyn, and Avenue B in the East Village. Not all of New York’s Open Streets will operate in the same way, nor should they. For busy strips like Park Slope’s 5th Avenue, a weekend closure with extensive programming makes sense. But other streets, like Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn, which cuts through a largely residential neighborhood, are quieter but no less successful. Community outreach efforts can help organizers design streets that meet unique neighborhood needs. But figuring out what a community needs is expensive. Kaufman wants the city to expand its community outreach efforts, especially in underserved areas with little access to parks that could really benefit from Open Streets. DOT already employs several streets ambassadors, a role Kaufman argues can be used to support Open Streets and create community buy-in.

At the same time, the decentralized approach, which leaves Open Streets implementation almost completely in the hands of community members, has floundered. More community voice and meetings may not quiet all criticism, and could invite those with strong opinions to step into outsized roles in community planning. Stakeholders across the board firmly recommend that DOT needs to play a more hands-on role in the program. Whether that comes alongside or at the expense of community input remains to be seen.

Come Spring, Hopes for a Permanent Program

In May 2021, Mayor de Blasio and the City Council passed legislation making the Open Streets program permanent. The legislation requires that the DOT manage or provide resources to at least 20 Open Streets in underserved areas, and provide resources to other streets as available. Privately, advocates are skeptical that the resources provided by the legislation will be enough to resolve deep disparities. Carolina Rivera, the council member who sponsored the legislation, acknowledges an undeniable tension underpinning the Open Streets program. Open Streets, she said in a recent CityLimits op-ed, must be better. So far, in its dispersed, community-driven form, the success of Open Streets has been less about policy and more about relationships, power, and resources.

Perhaps this legislation is the first step toward a stronger permanent program, but with the program flailing as it rapidly expands, winter approaching, and many Open Streets hibernating, Kaufman wonders what the new administration’s stance will be on that. “There are a lot of question marks about what impacts this winter will have on the program.”

In addition to deep spatial disparities, Adams must address looming questions of scale and structure and a straining relationship between volunteers and city agencies.

The program inherits structural problems from its origins as a crisis response to COVID. The Open Streets network, while administered by DOT, is not centrally planned. Instead, DOT fields applications from interested groups. The application process, it appears, is here to stay: DOT’s opened Open Streets applications for 2022 in December, asking returning and new partners to apply. With 246 streets currently on the portal, how many Open Streets that suspended operations will reapply? New legislation will require DOT to manage or provide resources for 20 sites directly, which could encourage more applicants, but leaves the Adams administration with important resource distribution decisions: how many will DOT directly manage and how many will they fund? Is it better to invest deeply in a few sites and ensure their success, or cast a wider net, raising the possibility that some under-resourced streets may shut down, discouraging communities and empowering critics? Depending on the approach, the city could end up with two programs: one city-managed, funded program at up to 20 sites, and another application-based, volunteer-run program with limited financial backing. With the current resources, Ydanis Rodriguez, the new DOT commissioner will face difficult tradeoffs.

Permanent infrastructure and permanent closures solve some volunteer and capacity problems; they are a key tenet of Transportation Alternatives recommendations. The 2021 legislation gives DOT the authority to create 24/7 open streets, but it’s not yet clear how they will use this power. Physical infrastructure, like bollards, boulders, or permanent barricades, can survive snow plows and harsh weather conditions, and may make Open Streets more viable in cold weather.

Many Open Streets have gone in and out of operation over the past year, and the DOT portal is updating with new streets. So while the numbers of active streets look grim, it seems plausible that even if individual Open Streets may fail, the program can succeed. Streets that had to shut down now, or may shut down this winter, may reopen. Whether next year’s program chooses to invest heavily in a few big, 24-hour Open Streets, or tries to pepper the city with smaller projects, the Open Streets that didn’t make it are opportunities for the program to grow in the future, provided the pilot program’s unmet promises don’t sour community appetite for open space. Some proposed solutions to Open Streets’s problems, if implemented, may also help quiet the program’s vocal critics. Better communication between agencies involved with street closures should help drivers. Permanent infrastructure could solve knowledge gaps about when Open Streets operate. Safer places to cycle may divert more New Yorkers to biking and out of cars, reducing traffic congestion.

As New York’s COVID-19 surge continues, the Open Streets Program will need to evolve again if it is to survive the winter freeze. Open Streets, where they are working, and even where they sputtered out, are beloved in many corners of New York, and worth preserving.

After the sun set, Caserta, dressed in a complementary Christmas Tree costume for the occasion, lit up the 25 foot evergreen at the corner of 5th Ave and 4th Street .“The program can work,” he said, “We [the organizers] sound a bit bitter because we have to deal with all the problems. Everyone else is enjoying themselves.” I asked Ashley and Lauren if they’d be back when 5th Ave closed to cars again next year. “Definitely,” Ashley replied.

This is a topic that is close to my heart… Cheers! Where are your contact details though?