While social media is known to manufacture outsize outrage, there is one case where I believe it has not gone far enough: Munger Hall. Much of the widespread criticism of Charles Munger’s design for student housing at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) addresses the direct impact on the 4,500 students that will live in its windowless apartments, while the broader narrative consequences of the project are treated as an afterthought. Beyond the direct impacts to UCSB students, Munger’s plan has added another dent to the reputation of dense, communal living in the United States–features of housing we should thoughtfully consider as our country faces demographic shifts, increased housing costs, and environmental threats.

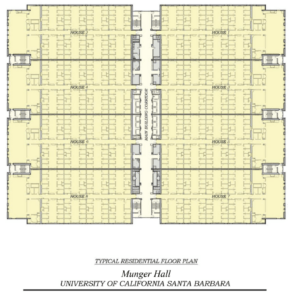

Munger’s design is ruled by tightly-packed eights: eight bedrooms per suite, eight suites per house, eight houses per floor. Each unit is standardized to facilitate modular construction methods, a feature that UCSB lauds for its ability to “minimiz[e] costs by maximizing the number of beds”. The result is a rigid, monotonous, and claustrophobic floor plan that is overwhelming to the average American.

Proposed floor plan for the Munger Hall (top), exterior visualization (bottom). Source – UCSB Office of Strategic Asset Management

While the backlash Munger Hall received is well-deserved, it is a shame to see people write off density as a whole due to Munger’s misguided attempt at architecture and housing. As America sees increases in single-person households, nationwide housing shortages, and the existential threat of a humankind-driven climate crisis, finding ways to promote sustainable living and communal ties among Americans grows increasingly essential. With benefits in terms of increasing the housing supply and lessening climate impact through facilitating the use of public transportation, increasing housing density in a thoughtful, strategic fashion throughout American cities is a great way to ensure housing access and affordability.

However–simply put–dense housing only offers a sustainable solution if people want to live in such buildings. Unfortunately, Munger Hall is only the most recent installment of unappealing, dense arrangements within America. Much of the high-rise public housing built during the 1950s drew inspiration from Le Corbusier, a “pioneer of Modern architecture”. The failure of these public housing projects–symbolized in the dynamiting of Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Missouri–is famously known as the day Modern architecture died. Despite the federal government’s disregard of the funding and management needed to sustain the projects after their construction, the lasting impression on many Americans is that dense, affordable housing is destined to fail.

Munger’s design makes it all the more tempting to believe that housing made affordable through density and standardized modular methods is simply not a feasible option for America’s cities. However, projects like Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 work to show that there is more to dense housing than endless rows of compact boxes. Modularity is not rigid or monotonous in Safdie’s work, but instead endlessly adaptable: the interlocked series of prefabricated boxes could be rearranged to fit different family sizes, community venues, and site conditions. The fact that apartments within Habitat 67 are now selling for $1.3 million illustrates that the issue lies not in dense, modular housing design, but rather in the ability of governments to maintain housing affordability.

Habitat 67: a 12-storey, 158-unit housing complex designed by Moshe Safdie. Source – Tourisme Montréal

Munger Hall is especially harmful as it, again, shifts the cultural narrative of dense housing to issues of design, rather than failures of social policy. Above all, people should be able to access housing that meets their unique needs. However, so much of what we want from our homes–what we demand–is limited by what we know to be possible. In this way, architects and planners have a special responsibility to generate innovative housing typologies that will meet the growing pressures of demographic shifts, economic crises, and climate change. Although Munger touts his design for student housing as a “fix” to Le Corbusier’s errors, his work has instead strengthened American resistance to housing density. We need more advocates willing to thoughtfully work with communities to find creative and sustainable housing solutions, and less billionaires using their resources to impose their vision of ideal living onto the masses.