The world is full of automation. Perhaps most common are manufacturing and industrial automation, which increase efficiency, consistency, and safety. Removing human interaction in favor of machines generally reduces waste, error, and the potential for injury. Nowadays, automation is likely most salient in the automotive industry. I refer, of course, to the cars themselves that are becoming automated, and not the manufacturing processes for cars, which have evolved since the early 1970’s. Self-driving vehicles, which include private cars as well as eighteen-wheelers used in the trucking industry, help to address the same issues as other automated processes. Removing human error can increase efficiency, and safety on the road, greatly reducing the number of accidents and road deaths. Looking at the advancements made in autonomous vehicles in the past decade or so, one begins to wonder why human beings still have any part in the operation of New York City subways. The answer is more complicated than it may seem. It not only involves the integration of technology into parts of a system that can be at least 100 years old, but also politics involving a large number of workers and the politicians that represent them.

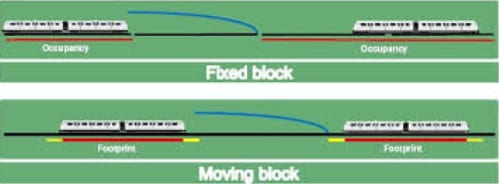

Image 1: Fixed Block, or Block Signal, Compared to Moving Block, or CBTC

Image 1: Fixed Block, or Block Signal, Compared to Moving Block, or CBTC

Fully automated subways are not necessarily a thing yet, despite my hopes that they were out there somewhere. The implementation of Communication-Based Train Control (CBTC), however, is getting us one step closer. Much of the NYC subway is still manually controlled through signals that let subway operators know where trains are relative to them on the tracks ahead. For example, the block signal system that operates out of the West 4th Street station has been in use since the 1930s. It is less precise, requiring more space between cars, and has more room for human error. The system operators do not actually know the exact locations of the trains within about 1000 feet.

CBTC, on the other hand, uses automatic, computerized signaling that is extremely precise, and durable. This automatic and constant signaling communicates the speed, exact location, and braking distance of each train. This effectively allows trains to “speak” with each other through the system, so they can travel closer together and more frequently. Though not technically automation, CBTC is certainly a move in that direction and does have similar effects. CBTC is currently in use on the L and 7 Lines, and while NYCT President Andy Byford wants to implement more CBTC throughout the subway system as part of a $40 billion plan over 10 years, the MTA already has enough money problems.

One way to partly address that problem that is often referred to is a switch to one-person train operation. NYC subways are generally staffed by two people, the operator and the conductor. The conductor makes announcements and operates the doors. A clear way to greater efficiency and lower costs when complemented by increased automation, the MTA has pushed for one-person train operation in the past, but is constantly at odds with the Transport Workers Union on this issue for obvious reasons. A bill was recently introduced by New York State Senator Kevin Parker of the 21st district in Brooklyn, that would prohibit one-person train operation on New York City subways. While it is certainly understandable that transit workers are essential to our city’s functioning, it cannot be ignored that they will be increasingly replaced, at least partly, by automated processes that are more efficient and safer.

Image 2: West 4th Street Block Signal Switchboard From 1930s

Image 2: West 4th Street Block Signal Switchboard From 1930s

As the subway system in NYC gradually implements more and more CBTC, it will have to slowly stop hiring as many train operators, and let conductors go through attrition, similar to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, so as to have the lowest possible impact on working-class families. It would be catastrophic to fire so many MTA workers at once – an outcome the city has thankfully avoided as recently as this February. Still, it benefits no one in the long run to think that New York City is the exception, while so many other cities make progress in this regard. Technological advancement in New York City will never just be about capability; it will always impact people we may not consider at first. In this case, the livelihoods of so many people are tied to a certain way of doing things. This is crucial to take into account when making technological transitions.

Cover Image Source: What Does a Conductor Do? (NYC MTA)