The COVID-19 vaccine has been on our minds since New York City went into lockdown on March 22, 2020, yearning to return to the busy streets and life of our beloved city. 9 months later, the COVID-19 vaccine was approved by the public distribution by the CDC. The first dose in the United States went to Sandra Lindsay, a Black intensive care nurse at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in Queens, New York. The vaccination was viewed as a symbolic effort that Black, Indigenous, and communities of color could trust the vaccine and available for them. In the United States, Black Americans are 1.5 to 3.5 times higher for risk of COVID-19 infection than white people, and Hispanics comprise 21% of the COVID-19 death rates. Due to these sharp racialized inequities, communities of color were promised to be prioritized in the vaccination efforts. Yet, white New Yorkers have received 48% of the vaccinations, and only 11% of Black New Yorkers and 15% of Latinx New Yorkers have received vaccines.

Since the release of the vaccine, there has been a change in presidential leadership. President Biden has signed 24 Executive Orders to undo Trump’s policies and proposed the 1.9 trillion-dollar stimulus package to accelerate the vaccine rollout in the fight against the Coronavirus. Among them, there is the Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. The Executive Order establishes an Equitable Data Working Group that mandates having federal datasets disaggregated by race, ethnicity, gender, disability, income, veteran status, and other types of demographics. Disaggregated data is crucial for understanding the growing importance of data, especially related to creating anti-racist policies amid a pandemic that has shown stark nationwide racial, social, and economic disparities.

Disaggregated data is the most salient part of the execution of equitable, nationwide vaccine distribution. The state of New Jersey has done a fantastic job of creating a transparent COVID-19 dashboard. The data is disaggregated by gender, race/ethnicity, age group, and the vaccine brand administered to the residents. Yet, due to the ability of the 50 states and territories to be able to govern their COVID-19 response (with only 37 states along with Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. that have a mask mandate in place), the consistency in response efforts is likely to trickle down to lack of data collection. Recently, the New York City’s Department of Mental Health and Hygiene stopped releasing disaggregated vaccine distribution data as it showed the startling racial disparities among communities of color. Without this crucial data, it is nearly impossible for public health resources and vaccine coalitions to direct their resources to the populations that need the help the most.

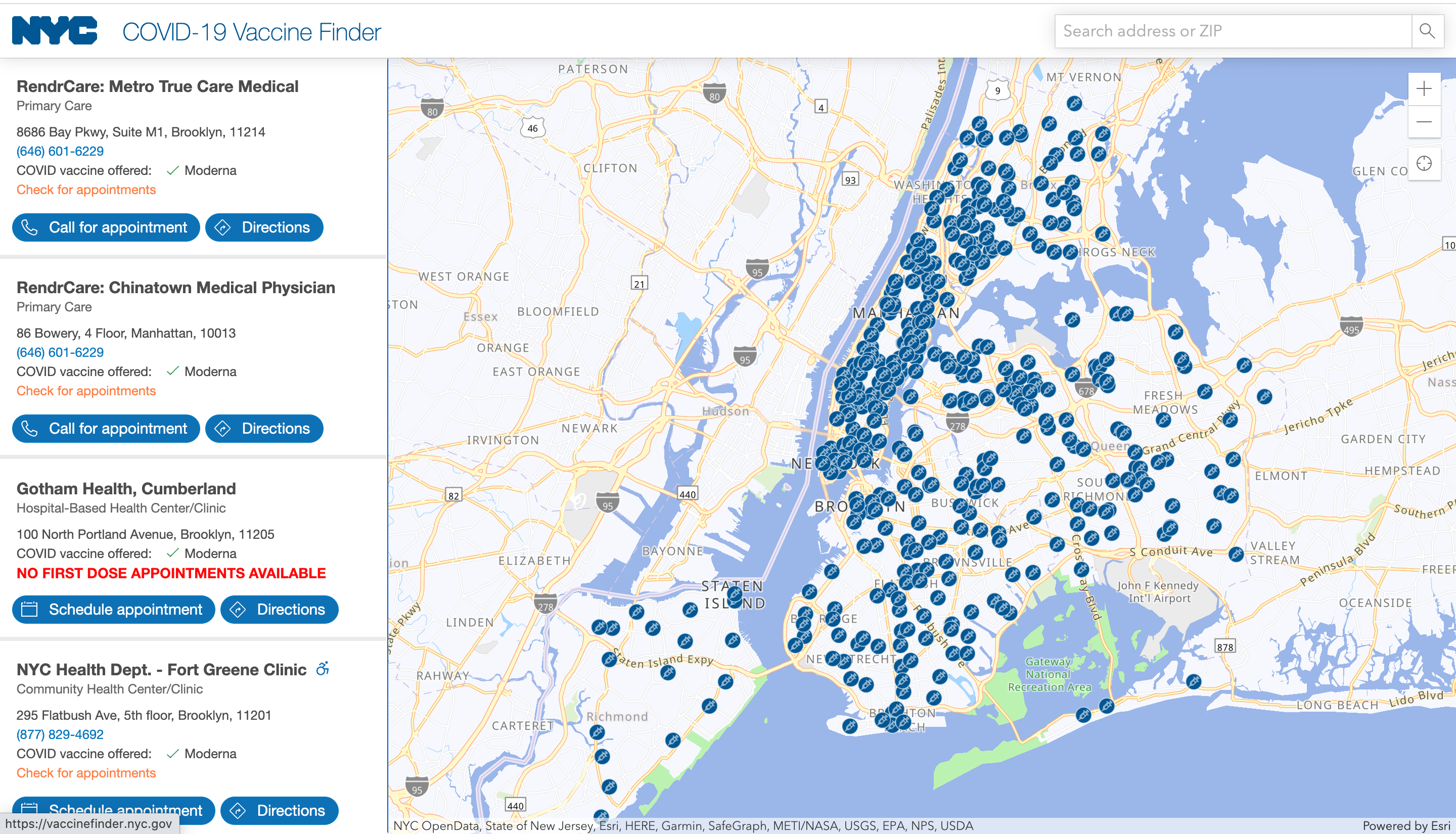

However, the placement of vaccination sides doesn’t necessarily target the intended communities. A vaccination site in Washington Heights, an area with a high concentration of Dominican New Yorkers, reported that white people received the most vaccines. The vaccine distribution efforts, while strong, were not created with an anti-racist lens. Dr. Bejar from Columbia University Irving Medical Center said, “When the vaccines are primarily distributed through a smartphone application in English to whoever refreshes the application first, longstanding structural inequities will replicate themselves unless the medical community makes a conscious and consistent effort to address them.”

There is a difference between intent and impact– the intention was in the right place. However, the effect was that the most negatively affected communities are still being the most underserved. It may be even more impactful to utilize platforms that immigrants know, use, and trust. Unfortunately, most of the time, sites like Facebook and messaging platforms like WhatsApp are known to be superspreaders of misinformation. It’s important to hold both contradicting truths and find a way to use the existing media trusted by communities of color.

Also, there is an unspoken amount of burden placed on communities of color, specifically healthcare workers. Bilingual healthcare workers are charged with their job responsibilities, acting as a translator, and consistently asked for their labor as the informal DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) person on their teams, resulting in constant fatigue. Politicians of color and grassroots advocacy groups are asked for their expertise for vaccine rollout, with little to no mention of compensation for their labor, in addition to their existing responsibilities.

Imagine what it would be like if residents and community groups could suggest the vaccination sites within their neighborhoods. The New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) has found a way to promote meaningful community engagement in the digital age by permitting the public to give feedback on maps for Citi Bike’s phase 3 expansion. Adopting a similar technology to COVID-19 vaccination sites would allow community members to have more autonomy and voice to directly communicate with local government officials about where the vaccination sites would be the most utilized by people of color. Additionally, creating an interactive mapping tool could also ease the burden for the people of color that are already involved in the vaccine distribution process.

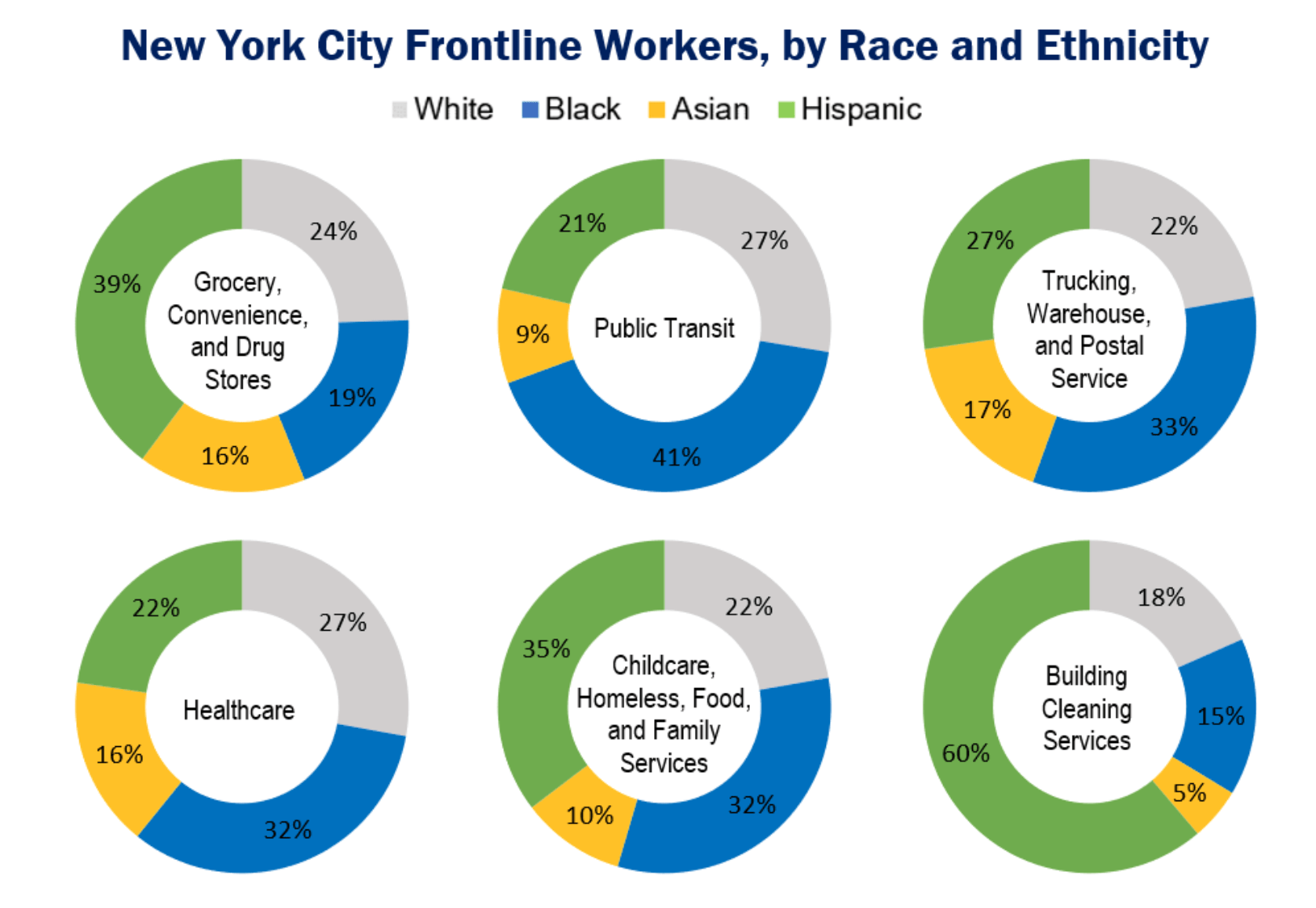

Additionally, there is a distinction that needs to be made among- serving essential workers and whether they work in-person or are still allowed to work from home. A possible future concern is whether or not white people are getting the vaccine because they are deemed to be “essential” versus being an actual frontline worker. If the risk is not there, and they are not immunocompromised, then those who are frontline workers should be prioritized above those who are essential workers who work from home because they are not risking exposure by working. According to the NYC Comptroller’s Office (graph listed below), New Yorkers’ frontline workers are disproportionately Black and Latinx/Hispanic, which heightens the risk of COVID-19 exposure.

Image: New York City Frontline Workers (Source: New York City’s Comptroller Office)

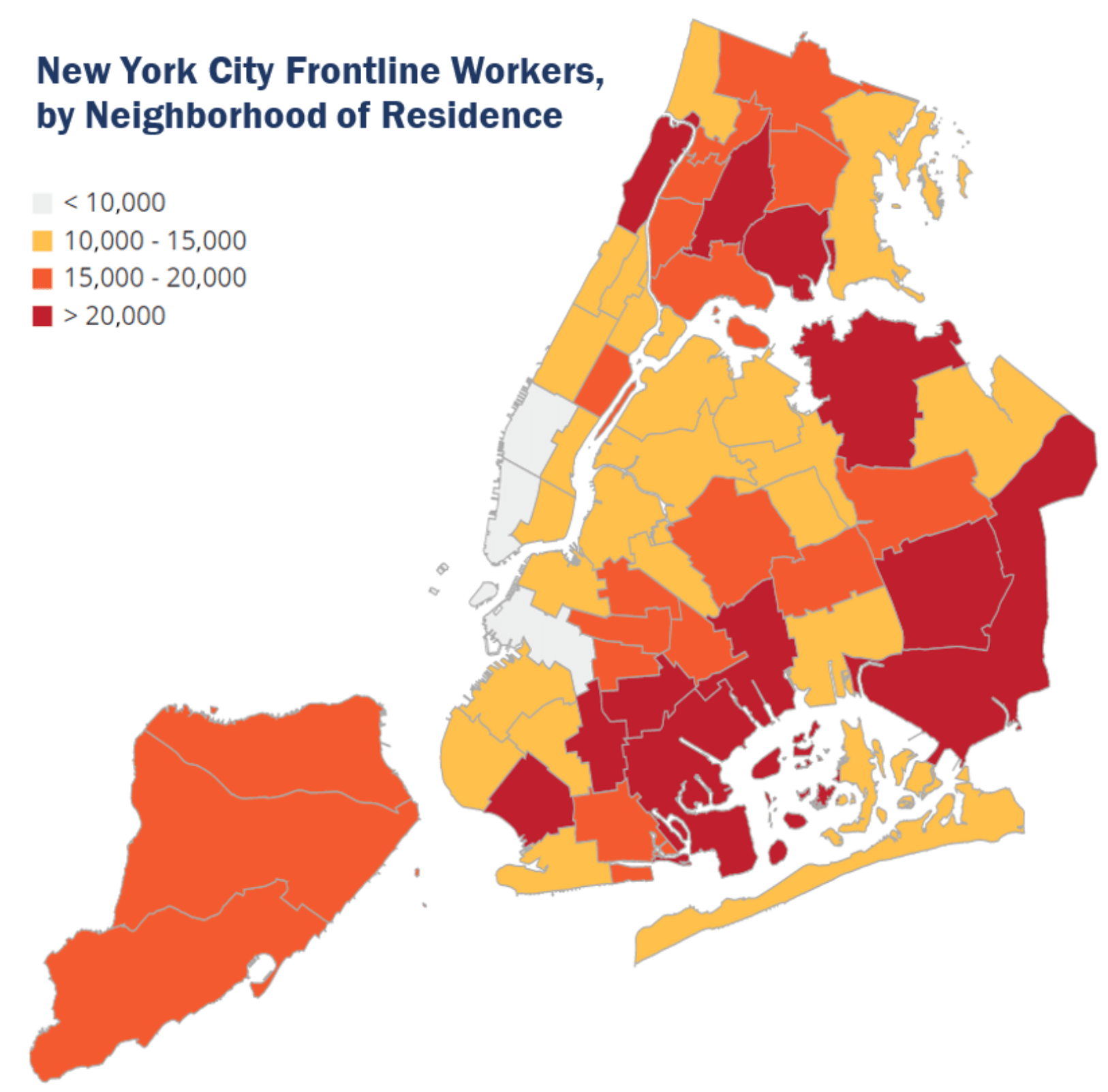

Image: New York City Frontline Workers (Source: New York City’s Comptroller Office)

Thankfully, the vaccine distribution sites correlate between the neighborhoods of essential workers’ residents. However, this means that white people travel outside of their neighborhood vaccination into others more likely than not. Perhaps this is due to the lack of vaccines or appointments or difficulties in accessing the website itself. Regardless, the racial disparities and undeniable inequity in vaccine distribution bring me to my point of potentially creating a rule that allows people who live within specific zip codes to be vaccinated at a site above others, especially if they are an essential in-person worker.

The fight against COVID-19 is far from over, with a Bloomberg report forecasting that life will “return back to normal” at a 7-year pace with the current vaccination rates. To beat these odds, it’s even more important to continue to use disaggregated data to target communities, such as frontline and essential workers, who need the vaccine the most.

Nonetheless, it’s important to remember the point of disaggregated data- it should be used as a tool to ensure that the underrepresented and marginalized groups gain access to the vaccine. Oftentimes, the misinterpretation of disaggregated data is that race/ethnicity is misframed as a causation for the socioeconomic/health disparities. Rather, the racial/ethnic disparities in disaggregated data should be used as evidence to prove the inequities that continue to perpetuate inequities within the current American health system that disproportionately impact low-income Black and brown communities. From there, policymakers and healthcare experts can gain a more holistic understanding of why the vaccine distribution disparities are as stark as they are.

Cover Image Source: Insurance Journal