by Ben Listman

In Farhad Manjoo’s New York Times Op-Ed titled, “I’ve Seen a Future Without Cars, and It’s Amazing,” he argues for the reclamation of space from the automobile in urban settings, particularly New York City. Accompanied by compelling images from Vishaan Chakrabarti’s Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU), the article explains how reallocating space from cars to pedestrians, bikers, and public transit would greatly increase the city’s streets safety and efficiency. In fact, the article, and the PAU proposal that these images go along with, argue for banning private cars from Manhattan altogether. In addition to its forward thinking and compelling ideas, this article unwittingly illustrates how discussions in innovative planning and the future of cities seem to often gloss over an ever-growing portion of our population – the elderly.

Image: 125th Street Before and After – Practice for Architecture and Urbanism

Image: 125th Street Before and After – Practice for Architecture and Urbanism

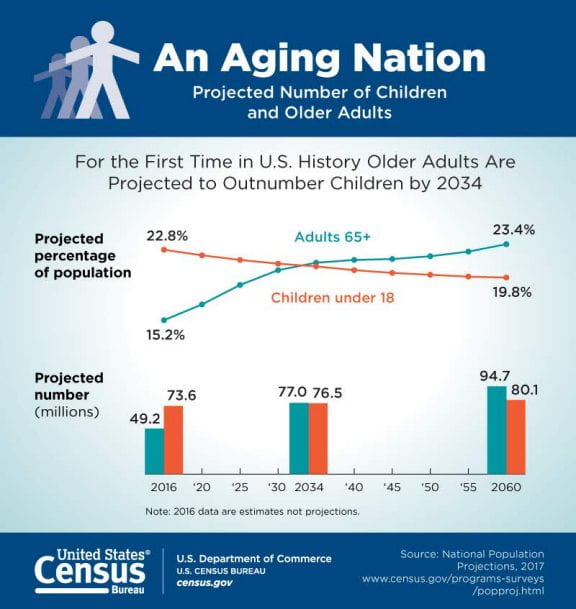

According to the United States Census Bureau, adults aged 65 and up will account for about 21 percent of the US population, up from around 15 percent today. For most of these aging adults, public transit and even microtransit will be sufficient for getting around the city. Better public transportation options and more walkable streets will create a better environment for a growing elderly population. However, when trouble with mobility becomes a factor, transit becomes much more difficult. New York City has its own problems in accessible public transit, with only about a quarter of subway stations being ADA accessible. In addition, paratransit has been found to often abysmally serve those who need it.

Image: Projected Number of Children and Older Adults – United States Census Bureau

Image: Projected Number of Children and Older Adults – United States Census Bureau

Manjoo’s article itself may not actively ignore the elderly population. After all, it is more focused on a lack of cars in the future city than anything else. According to PAU’s proposal, pedestrians would get increased sidewalk space, cyclists would get more protected bike lanes, and buses could get more dedicated bus lanes. There would be plenty of space left for rideshare vehicles, paratransit, emergency vehicles, and delivery trucks, which would then be able to drive along decongested roads. Manjoo makes the point that not only are vehicles dangerous, killing people in crashes as well as through the negative health impact of pollution, but they also take up an absurd amount of space for the amount of people they move around. A city with greater access to public transit and greater infrastructure for microtransit will surely be a safer and more efficient place.

As a cyclist often frustrated by cars around the city, the idea of banning them in Manhattan would never have given me pause. However, my grandmother had recently fallen in her apartment and my family and I have been using our car to get her around the city. Whether it is getting her home from a rehab center or getting her across town to her doctor, our car seemed the only viable option. Our car is certainly preferable to a rideshare where there might not be enough room for any combination of me, my mother, my grandmother, her aid, a walker, and a wheelchair.

On the one hand, a private car is clearly preferable in situations like these. On the other hand, transportation focused on only one person cannot alone justify owning a car in the city. My preoccupation, then, with the idea of banning private cars from Manhattan, is not the need for the cars themselves, but the need for many more alternatives that can accommodate those with mobility problems. Microtransit might evolve to also accommodate those who cannot just bike or stand on a scooter. Paratransit also has the potential to adapt to more flexible routes responding to demand through apps. Cities around the US are already experimenting with incorporating microtransit with public transit.

I agree with Manjoo that “the real way to revolutionize transportation is to think beyond the car entirely.” As long as I live inside, or even near a city, I certainly do not plan on owning a car myself. However, If American cities (and hopefully the entire country) are ready to move beyond the car, but all we have to offer to the disabled and elderly are inaccessible public transit, unreliable paratransit, or a private car, then we have very far to go indeed.

Cover Image Source: The New York Times