Final Reflection: A Cairene urbanist in New York City

The identity of a city goes beyond the demographic composition and the built environment. A city is formulated by a multitude of actions, or intangibles, that create a change within the city. These actions include events, community interventions in a neighborhood, and social and economic interactions. Such actions form an intangible network that connect to the city’s institutions, governance, as well as the built environment. An urbanist’s role is to synthesize the intangibles of a city and present it in tangible forms like stories, maps, images, as well as buildings and spaces. Urban research is a way to make sense of the interwoven characteristics of a place, which are often nonquantifiable.

David Harvey identifies the process of urbanization, and subsequently, the city, in terms of spillover. He explains that a city is formed because of a surplus of characteristics such as density, and consumerism, all of which affect the way a city is governed and shaped. In this essay, I will present the city’s intangible actions as a type of surplus. Furthermore, I will use a specific action, street vending, as an example to explain how the city’s intangible network affects economic and social interactions and shapes the way we, as urbanists, identify the city.

Growing up in Cairo, the city’s identity was often framed with informality. The Lack of regulations resulted in informal practices, which are exacerbated in the form of informal settlements as well as ungoverned economic transactions. Cultural norms and informal agreements often binds economic transactions as well as the spatial structure of the city. Almost all the city’s actions are categorized as informal, as opposed to the formal governing actions. This allowed the city’s intangible network to become more tangible, and hence, the city is easier to understand.

Street Vending on a side walk is illegal in Cairo. As you encrypt the physical scene of a Cairene side walk, you will be able to identify a line between the legal and the illegal, the formal and the informal. A street vendor’s cart is informal, both in terms of how it was purchased and its current location on the sidewalk. The economic transaction between street vendors and the public is informal. In sum, the street vendor comes from an informal settlement to informally occupy a space, in a formal sidewalk.

My experience in Cairo made me realize the city as a host of two opposite actions: the and the, the informal intangible actions and the formal governing actions. When I moved to New York city eight months ago, I applied the same rationale in an attempt to understand the city. One underlying fallacy in this approach, is assuming that stakeholders can always be categorized into two groups. I saw street vendors and immediately called “informality”. However, Street vendors in New York are an example of how complicated and intangible the urban network in the city can be.

Encrypting the physical scene is more complicated in New York city. Street Vending is legal, in most sites. Street Vendors might be licensed; however, their assistants are usually not, because they are often undocumented immigrants. The cart’s location and the economic transaction between the street vendor and the client are bound by multiple stakeholders such as the city, the Department of Consumer Affairs, and the Business Improvement Districts (BID). These stakeholders create conflicting regulations and street vendors end up operating half formally and half informally to maximize their economic benefit. For example, parts of a transaction are formal while others aren’t. Vendors do not record a sale when the customer pays in cash, but the sale is automatically recorded when a customer pays with a debit or credit card. As a result, taxes are not deducted from the informal cash transactions, but a 15% tax is deducted from the formal non-cash transactions.

The change caused by the multitude of actions in a city actions goes beyond creating the city’s intangible identity. Street vending causes a spatial redistribution and offers such groups an opportunity to own a private space in public areas where they might be considered unwelcomed. For example, street vendors often live in low-income areas such as the Bronx and Benson Hurst. However, they are able to operate in high income areas in Manhattan or recently gentrified areas that BIDs have not yet controlled.

Identifying the different stakeholders and their roles was essential in understanding street vending. The position of a stakeholder in the city influences the intangible actions of the residents and consequently their share of the pool of resources in the city. The pool of resources includes economic opportunity, public space and their part in the decision-making process.

One of the underlying roles of an urbanist is to identify the different stakeholders of a city or a neighborhood. This role is the key for participatory urban development, which allows the community to take part in the decision-making process of a development project. The participatory approach is adopted by multiple urbanists, as well as advocacy groups in New York, among which is the Women Housing and Economic Development Corporation in the Bronx. This approach allows WHEDco to identify the community’s intangibles as needs and create development proposals to address them. In other words, they synthesize the intangibles into a tangible output, which is the urbanists main role.

Storefront Improvement Project

This project was part of LISC’s Commercial Corridor challenge, which WHEDco had won last year. In this map, I listed some examples of the Business that participated in WHEDco’s storefront improvement process. Photos attached are of the business’s storefronts prior to improvement.

Advocacy through Public Space: Right to the City

On Friday, July 13th, I assisted WHEDco in organizing the Bronx Music at Melrose Festival. The annual festival is meant to celebrate the Bronx’s music heritage with the residents as well as introduce WHEDco and its diverse services to the community. To me, however, the festival was an opportunity to gain new insights regarding my research for advocacy and public space. The BM@M festival offered a glimpse of how public spaces can be used under different governing institutions, regulations and activities.

The event took place at E 161st street, between Melrose and Elton Avenues, where the street was nestled between two mixed-use blocks: Block A on the Southern side and Block B on the Northern side. Block A had continuous commercial spaces at the ground level such as open sidewalk cafés and transparent storefronts, while Block B had two non-residential spaces solid metal doors. Although both sides were identical in terms of design, the vibrancy of Block A made this side of the street more welcoming and had a larger share of pedestrian flow.

As we started laying out the festival’s booths and tents, I started to think about the difference in how pedestrians perceived both sides of the street and this raised an important question: To what extent can street interventions affect the individual boundaries of a person’s comfort zone in a public space? So, I started thinking of the festival as a way to experiment different spatial organizations of the street.

During the festival, the street’s function changed from being a pathway for cars into a pedestrian friendly public space. Police were present at both ends of the street, which increases safety.

After the festival, and before the police remove the barricades, children started using the street as a playground and the two sidewalks became connected by this new intermediate space. In that brief moment, the street was in a state that was neither formal nor informal, but was absolutely owned by the community.

Advocacy through Public Space: Introduction

In addition to presenting facts and data, my research project explores the dynamics between residents of the Southern Boulevard area and the City, as well analyses WHEDco’s role as an advocate and a mediator. Understanding the role of each of these three stakeholders and their position in a dispute is an integral part of the community needs assessment. In this assignment I will explain WHEDco’s role in the advocacy realm and briefly talk about the book that will help me unravel the current dispute between the Bronx community the Department of City Planning (DCP).

WHEDco provides various community development services in the Bronx as well as contributes by a large share of affordable housing in the area. Providing community services often require collaborating with municipal authorities, funding agencies, and other government institutions, in order to facilitate their implementation. These collaborations are dialogic in nature and WHEDco is often the voice of the South Bronx Community. Although the assessment allows WHEDco to accurately advocate for the community’s needs, it does not guarantee that the city will choose to respond to the most pressing needs among them.

As the local community continues to advocate for their right to make decisions regarding the DCP’s developing, it is essential to empower the community’s position in WHEDco’s dialogue with the city. WHEDco’s negotiation efforts goes beyond representing the community in the city council. It empowers residents and business owners by claiming their right for public and communal spaces in the neighborhood. This is achieved by providing streetscape elements and organizing events that increases the community’s spatial share of the neighborhood. (Photo: Children participating in WHEDco’s mural painting project in Goble Playground)

In his book “Dealing with Differences: Dramas of Mediating Public Disputes”, John Forester uses examples of complicated disputes across the US to explain the process of mediation in planning and policy making. John is a scholar on the micro-politics of planning and is a professor at Cornell University where he teaches Urban and Regional Planning. He published this book in 2009 as a sequel for two books on the same topic published in the 1990s. As the book lays out the process of mediating disputes, I will interpret this process in my research from a spatial perspective, as well as analyze how street elements and design regulations can alter the dialogue between the community and the government.

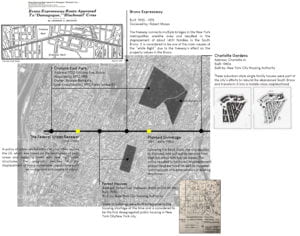

Historic Context

Unlike neighborhoods in Manhattan, almost every planning policy conceived by the City throughout the past century was realized in South Bronx, regardless of the community’s disapproval. From the “urban renewal” to “planned shrinkage”, the city implemented plans that greatly affected the Neighborhood. For this assignment, I created a timeline of important City projects and policies that played an important role in shaping the neighborhood the way it is today.

Photo References:

Bronx Expressway: CHARLES G. BENNETT. New York Times (1923-Current file); New York, N.Y. [New York, N.Y]15 May 1953: 1.

Forest Houses: New York City Housing Authority. Transportation facilities: Public and Institutional Buildings, etc. Project NYS Forest Houses. (created on 2018-04-23 by Matthew Martinez , NYU Gallatin; Instructed by Rebecca Amato. Updated on 2018-05-14 by Matt Martinez , NYU Gallatin; Instructed by Rebecca Amato. ) << https://www.theclio.com/web/entry?id=59210 >>

Charlotte Gardens: Startsandfits.com. (2018). Starts and Fits. [online] Available at: http://www.startsandfits.com/2006/04/bronxs-green-housing-boom.html [Accessed 1 Jul. 2018].