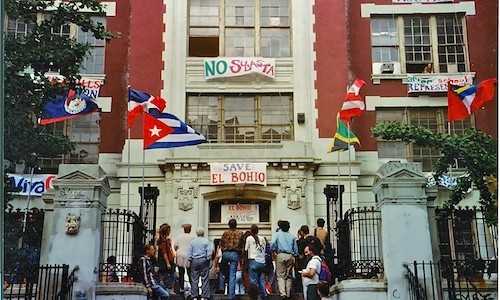

Picture from East Village Community Coalition

Following the New York City fiscal crisis of the early 1970s, the city’s decision to cut funding on public services and housing subsidies was particularly devastating to many low-income neighborhoods, including Loisaida. Now experiencing real estate abandonment and disinvestment, residents were not only prey to crime, absentee landlords, and lack of access to basic goods and services, but also to cultural abandonment by closing arts and social service agencies.

In this bleak environment, a mejore, no se mude (improve, don’t move) mentality among Puerto Rican residents begat a long and fascinating movement of community activism that used sweat equity to turn squatters into landlords, retrofit buildings, create community gardens and geodesic domes, and even install a wind turbine and solar panels to generate electricity. However, the activism did not only work to improve the quality of life in Loisaida, but also moved on to cultural activism in addition to –and a central part of– the urban and ecological activism.

One of the most fascinating historical organizations that set out to remedy this was CHARAS, a holistic kind of organization that multi-issue organization that addressed issues as wide-ranging as housing, environmentalism, education, job training, and the arts since its founding in 1965.

“Other groups would do the detail management, pero we became the holistic group, trying to encourage people to create ideas,” said CHARAS founder Carlos “Chino” García in an oral history interview with Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

Squatting in abandoned p.s. 64 at 605 East Ninth St., re-dubbed El Bohío (ie. the shack) in 1979, CHARAS eventually got a lease from the city and renovated the building to host classes, studio spaces, after-school activities, and performance spaces for dance, film, and theater.

In addition to creating El Bohío, CHARAS also sponsored murals like La Lucha Continua/ The Struggle Continues (1985-86) an enormous muralism project that captured issues of gentrification, police brutality, immigration, feminism, racism, and U.S. military intervention across a series of 26 murals.

However, after many renovation efforts were successful and the neighborhood began gaining vitality, community organizations shifted their focus from rebuilding to cultural preservation and to combatting gentrification. Eventually, CHARAS was sold to real estate developer Gregg Singer for $3.15 million in a 2001 public auction and was left without a permanent home, despite many efforts by community activists.

According to 2018 New York Times article, the Bloomberg administration has expressed interest in reacquiring the now-empty building, but no further steps have been made.

Nevertheless, despite the closing of El Bohío, many organizations have carried on the legacy of cultural activism in the neighborhood that will not soon be displaced. Holding down a fifty-year lease on the 10,000 square foot facility at 9th Street and Avenue C, the Loisaida center hosts arts workshops and performance spaces in addition to organizing the annual Loisaida festival.

Founded in 1996 to address the historic lack of services available to girls and young women, the Lower Eastside Girls club boasts a 35,000 square foot community center that offers programs in the arts, sciences, leadership, entrepreneurship, and wellness for girls in middle and high school.

Named after the Puerto Rican poet Clemente Soto Vélez, the the Clemente Center was was founded in 1993 in former P.S. 160, a collegiate neo-gothic building at 107 Suffolk Street. Centering many of its efforts on Latinx cultural preservation, the Clemente Center provides subsidized studio, rehearsal, office, and venue space to individual contemporary artists, curators, independent producers, and small arts organizations.

However, despite the headway made by all of these organizations, much progress is yet to be made. Even as the LES continues to gentrify, the neighborhood saw a 15% increase in poverty between 2010 and 2016 while citywide poverty rates decreased over the same period. As everywhere, class, race, and gender act as gatekeepers to the arts and culture, and providing physical spaces and funding for more diverse creators to is only a start for the needed disruption.

Leave a Reply