One aspect of community archiving that has been at the forefront of my mind while working with the Puerto Rican Cultural Center this summer is the contrast between our project’s “starting from scratch” reality, and the “typical” structure of an archive that is based in an institution. Even a small organization, historic site, or business that has an archive associated with it, has a level of resources and structure already in place, which our team had to design without much background support. (The structure of the PRCC itself is fairly atypical in how it operates as an umbrella organization overseeing and linking many projects and programs.) A large part of my role this summer was to bring a knowledge of archival structures and processes to a disparate collection of materials and history that has been collected, worked on, and moved around by many different people throughout the existence of the PRCC, mostly without any specific intention of long-term preservation. Being somewhat familiar with and invested in community archives practices and conversations, I was also aware that these “standard” archival systems have their own history of not always being suitable for the diverse needs of different communities.

Book by archivist Elizabeth Yakel, 1994

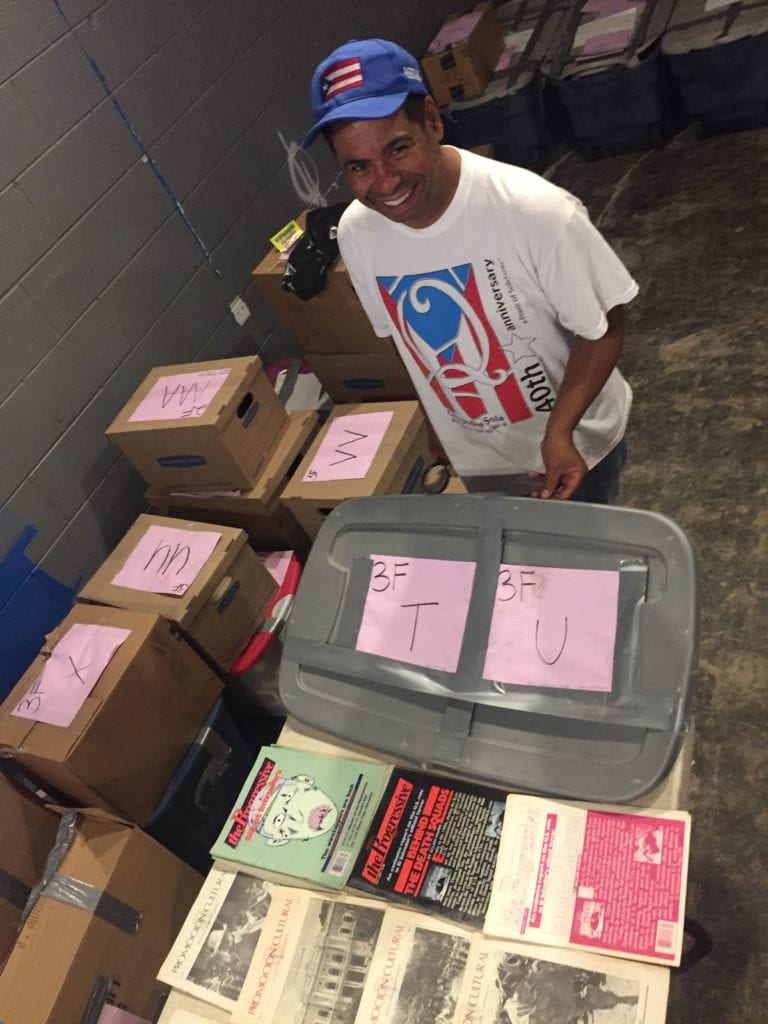

Furthermore, while there are certainly stories from many archivists that have had to go digging through piles of documents, or happened upon collections full of messy and physically dirty materials, the majority of institutions have archival documents given to them in some semblance of structure. Through some research surrounding “starting an archive,” I found that almost all articles and books on this topic are written from the standpoint of “building collections” from acquisitions, where records creators simply hand over neat and organized materials. This is clearly a simplified version of what archival acquisitions look like (the process can take multiple forms), but it is hard to find information about truly creating an archival collection from disparate materials that have been collected, without clear intention or organization, over a significant period of time. At the same time as the PRCC’s collection materials were being “discovered” and surveyed by the Archives Team (and the current state and structure of both digitized and born-digital materials was also being determined), the creation of an administrative structure and general overarching management tools needs to be decided. These two key tasks happening simultaneously is important for the success of the whole project, but managing the realities of this work is another challenge that most archives do not have to face.

An essential question that the Archives Team will need to answer in regards to an administrative decision that fundamentally relates to the archival collection, (and that every archive has to answer) is that of the colleting scope – what are the terms or boundaries for materials that do belong within this archive, and what kinds of materials or topics do not belong? While there is something to be said for inclusivity and wanting to save everything, no archive can or should collect everything (both logistically and theoretically!). This decision is often related to the mission of the organization or the archive; in this case, we know that the Community Archive will eventually include materials from the larger Puerto Rican Community as it relates to Humboldt Park and Chicago, so the mission and collecting scope will surely reflect this.

This process, of deciding what does and doesn’t fit into the scope of a specific archive’s goals, is often known as accessioning. Sometimes, items will not be accessioned because there is another organization that is already collecting in a subject area, and so they have a strong baseline where materials would be a stronger fit. Or perhaps, one groups’ archival needs and resources are not able to focus on artwork conservation, for example, so those materials must find a different home where they can be cared for better. The PRCC will define these terms for their Community Archive based on their general mission[1], which will in turn help with their accessioning process; but of course this is hard work and requires significant time and input! (It also requires knowing to some degree the materials that already exist – thankfully our initial work this summer made significant steps in accomplishing this stage.)

To aid the creation, implementation, and continuing support of new community archives, there are current projects in existence like the Community-Driven Archives initiative, a three-year grant through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Southern Historical Collection (SHC). Titled in full the “Building a Model for All Users: Transforming Archive Collections through Community-Driven Archives,” the SHC is creating partnerships with community archiving projects, creating tools for community archives to use in the aid of oral history collection and beginning preservation, and then sharing its processes so that they might be replicated, hence the “model” part of the grant title. Furthermore, other collaborative models are being funded and developed with unique community archives collections for digitization, where a post-custodial framework is in place in which one partner owns and provides the archival materials, another partner does the technical work of digitizing the materials, and a third partner with greater institutional capacity agrees to preserve the digital preservation master files.

One team member lending a hand as we developed a documentation process for tracking materials as we sorted them!

It is my hope that the lessons the PRCC Archives Team has learned through the initial founding stage of the summer can also be shared with broader audiences, developed, and built upon. While it is challenging to be creating an Archive without a well-structured institution that is already focused on preservation needs and information services (meaning the universities, libraries, historic sites, etc.), this will afford the PRCC Community Archive an opportunity to take the most useful examples from certain projects while also forging its own path and making decisions that are best for its own future needs, as well as the needs of the Puerto Rican community in Chicago.

[1] “The Puerto Rican Cultural Center is a community-based, grassroots, educational, health and cultural services organization founded on the principles of self-determination, self-actualization and self-sufficiency that is activist-oriented.”