While my research and work focus this summer has tended to lean towards the much more practical realities of founding an archive, I have tried to keep the “community archive” aspect of the project in the forefront of my readings and resources. It is essential, while working in a community with whom I cannot personally identify, but an organization who’s politics and values I respect and can support, that I consider the impacts of colonialism, race, class, and lived experiences beyond my own, especially as they relate to the historical power and function of archives (which are most often large institutions collecting a version of “mainstream” history within a “professional/formalized” structure).

Picking one source that I’ve used this summer to center these ideas would be difficult, but there are two clear inspirations which I’ll discuss below, for thinking through the relationship of history, archives, underrepresented narratives, accessibility, and “communities” of many shapes and sizes.

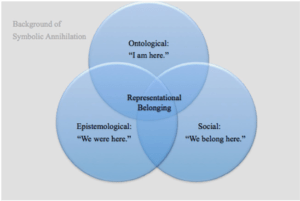

First, some of the work at the forefront of thinking about community archives has been done in the past 10-15 years by Dr. Michelle Caswell and related colleagues. Casswell focuses on the intersections of “archives, memory, public history, and social justice,” and how representation in an archive can effect peoples’ relationships to their own histories, communities, and understandings of their place in the world. I have been considering the concepts of representation within the “tripartite structure” that Caswell et. all lay out in articles that delve into the practicalities of community archives and how they can have a direct impact, “ontological[ly] (in which members of marginalized communities get confirmation ‘I am here’), epistemological[ly] (in which members of marginalized communities get confirmation ‘we were here’), and social[ly] (in which members of marginalized communities get confirmation ‘we belong here’).” [1]

“Figure 1. The impact of community archives in response to symbolic annihilation.”

The goal of this framework “is to conceive of and build a world in which communities that have historically been and are currently being marginalized due to white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, gender binaries, colonialism and ableism are fully empowered to represent their past, construct their present and envision their futures as forms of liberation.” This work in many ways builds on conversations of archival and historical representation and inclusion by other archivists working to challenge the standard systems of “professional” practice, such as Elizabeth Yakel, Terry Cook, and Andrew Flinn.

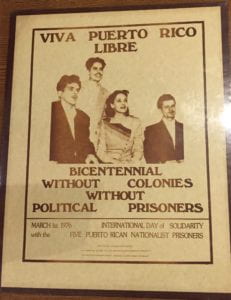

These ideas directly relate to the Puerto Rican Cultural Center, as they are consistently raising awareness of and fighting against the impacts of US colonialism on Puerto Rico, and dealing with related histories of displacement, racism, institutional violence, economic disparities, and more, that affects the diaspora community within Chicago. The goals of the community archive that we are building include making the community’s own history determinable and accessible in ways which “necessitate [its] own model of impact that centres the needs of marginalized communities.”[2]

Casswell also focuses on concepts of silences in the archive, especially in her 2014 book, Archiving the Unspeakable: Silence, Memory and the Photographic Record in Cambodia (The University of Wisconsin Press). I haven’t read this book in full yet, but from reviews such as this one by Karen Strassler, as well as from the contents structure of the book[3], is clear that Caswell relates directly to the other source I have been focusing on, Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon Press, 1995). Trouillot was a prominent Haitian scholar and anthropologist, who taught for 14 years at the University of Chicago, and who’s work engaged a number of interdisciplinary topics. (There is some worthwhile biographical information, as to his background and his work, here.) I was familiar with this seminal work through a class last semester, but have been grateful for the opportunity to read it again – Silencing the Past is “about history and power, [and the uneven] production of historical narratives.”[4] This if fundamentally tied to the construction of a community archive (essentially from scratch although the prospect of this project has been in conversation for some time), as we think about what documents, records and artifacts have been saved and lost, the hows and whys of this trajectory, how the history of the PRCC and Puerto Rican community in Chicago has been told, constructed, and experienced, and who has the power to tell it.

Trouillot delineates four separate moments that “silences” are present as they enter the process of historical production, which he stresses are “conceptual tools… [to] help us understand why not all silences are equal and why they cannot be addressed – or redressed – in the same manner.”[5] Here, you can see the structure from which Caswell is in part building from: silences exist at “the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).[6] In thinking through theories of history and archiving, these concepts are key to understanding that silences are always actively created, and that they are “inherent in history.”[7]

Trouillot uses this conversation to illustrate throughout the book three separate instances where silences impact our understanding of history in different ways, and he breaks down the production of that history. But it is worth extrapolating these concepts to thinking about the creation of this community archive at the PRCC. There is so much activity that has already gone into this present moment where we, a team of individuals all with a different relationship to the PRCC, to this community, and to these physical materials (and indeed different understandings of some of the materials, based on levels of Spanish fluency) are indeed making the archive, the second moment where silences are actively created. Of course, no archive can save everything, but we are making the decisions that will impact what types of facts, narratives, and history people can and cannot access into the future, at least from this specific framework. We are being critical and inclusive, and employing certain aspects of archival standards as well as considering when and how to break those rules; but we are asserting a very specific power here. This work will require further guidelines, documentation, and collaborative learning, but I hope that we, and every person who works on and engages with this project into the future, will continue to always be mindful of the power within history and its active production.

Trouillot uses this conversation to illustrate throughout the book three separate instances where silences impact our understanding of history in different ways, and he breaks down the production of that history. But it is worth extrapolating these concepts to thinking about the creation of this community archive at the PRCC. There is so much activity that has already gone into this present moment where we, a team of individuals all with a different relationship to the PRCC, to this community, and to these physical materials (and indeed different understandings of some of the materials, based on levels of Spanish fluency) are indeed making the archive, the second moment where silences are actively created. Of course, no archive can save everything, but we are making the decisions that will impact what types of facts, narratives, and history people can and cannot access into the future, at least from this specific framework. We are being critical and inclusive, and employing certain aspects of archival standards as well as considering when and how to break those rules; but we are asserting a very specific power here. This work will require further guidelines, documentation, and collaborative learning, but I hope that we, and every person who works on and engages with this project into the future, will continue to always be mindful of the power within history and its active production.

[1] Michelle Caswell, Alda Allina Migoni, Noah Geraci & Marika Cifor (2017) ‘To Be Able to Imagine Otherwise’: community archives and the importance of representation, Archives and Records, 38:1, 5-26, DOI: 10.1080/23257962.2016.1260445 ; also referencing Caswell, Michelle, Marika Cifor, and Mario H. Ramirez, “‘To Suddenly Discover Yourself Existing’: Uncovering the Affective Impact of Community Archives.” The American Archivist 79 (Spring/Summer 2016): 56–81. ; [for other seminal work in the archival field, see Caswell, Michelle and Marika Cifor. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in Archives.” Archivaria 81 (Spring 2016): 23-43.]

[2] Caswell et. all, ‘To Be Able to Imagine Otherwise,’ p. 21

[3] 1. The Making of Records; 2. The Making of Archives; 3. The Making of Narratives; 4. The Making of Commodities

[4] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, Boston, 1995; Preface xxiii

[5] Trouillot, 26-27

[6] Trouillot, 26

[7] Trouillot, 48-49

Great book to engage with! And I think I met Michelle Caswell last year at the American Studies Association conference, so glad to see her turn up here too. Of course, these are all important points — the way the archive reflects power relations in general, in the context of what survives, in the context of what gets interpreted. The PRCC’s project is radical insofar as it’s preserving untold histories of Puerto Rican life and struggle in Chicago. But it also has the potential to be conservative if it doesn’t allow itself the porousness of collaboration, community input, ongoing collection, and ongoing reimagination. That’s a tall order! And it’s tough when you’re also reflecting on your own positionality and “expertise” within this organization. What are creative ways to address the silences? What are standard ways? For example, oral histories can help to bridge silences simply because memory can fill in what was never documented. A collective statement on absence from the archival committee would also be interesting. Invitations to add to the archive could be useful and inclusive. What else are you thinking? Also, have I told you about critical fabulation? See: http://www.imagineic.nl/sites/default/files/files/Hartman%20Venus%20in%20Two%20Acts.pdf