Typography necessarily comes after writing because typography is a medium in which the substance, the writing, presents itself to reality. Vice versa, writing cannot come without typography as no substance can actualize itself without the form in which it realizes itself.

I find this relationship between typography and writing universal as the discourse of the form and the substance is. Similar relations can be found anywhere. The most profound analysis on this discourse comes from the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud and the study of commodities of Karl Marx. First, the psychoanalytic view of the dream presents perhaps the first proper analysis of this relationship: dream is the form in which the substance, i.e, the latent dream-thought — the subconscious thoughts consisting of our desires and wills actualize themselves. The same kind of analysis can be found in Marx’s analysis on commodities. The capital and the goods we normally accept one-dimensionally are in fact a form in which the actual substance that is the human labor (and land in some analysis) actualizes itself in the capitalist world. Such discourse can be easily interpreted as a paranoiac view of the reality. Paranoia is a condition in which one doubts that what one sees and experience is a facade of something ‘bigger’ and more meaningful, i.e., something essential. That, however, is when this discourse diverges from that of a metaphysics. In Platonic metaphysics, what we experience in reality is a mere ‘shadow’ or a form in which the ‘essence’ of the experience actualizes itself in the real world. Necessarily, the form, as a shadow, is a perverted and distorted materialization of the pure essence of the object. In that perspective, the hidden kernel of the experience, the ‘essence’ believed to be existing in the realm of idea becomes the object of analysis and the end in itself that arouses the fascination. However, as Slavoj Zizek points out, the central focus of the discourse of the form and the subject is not at the essence itself. The fascination of the hidden kernel resorts to a fetishistic fascination. In fact, the hidden kernel are, most often, things not ‘essential’ or most meaningful. For instance, the subconscious thoughts that actualize themselves in a dream are usually not something more meaningful or important than our conscious thoughts. If I dreamt of eating popcorn, it probably represents the subconscious desire of popcorn I had when I was hungry at 2 a.m.. The same is with the commodities. The hidden kernel of the commodities as a human labor is intuitional and, was deduced by many scholars that predates Marx. The focus, then, is why and how the substance, i.e., the hidden kernel, presents itself as the form in which we experience in reality. Why and how has the thought of my subconscious wills and desire presented themselves in my dream-thoughts? Why and how has the human labor actualized itself as a capital and a commodity?

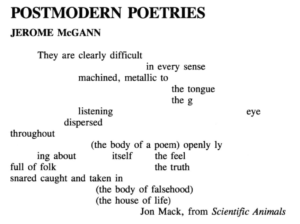

Same questions are worthy of analysis with the subject of typography. The questions we ask when making decisions on how to constitute certain typographic style grounds itself in those philosophical inquiries. Most viscerally, choosing which typographic style to use for certain type of texts based on the characteristics of the text can be thought of in the same context. The question is: How should the substance which is the writing present itself to reality? Is Comic Sans a proper form in which the substance of a resignation letter can be actualized in reality? Is Times New Roman a proper form in which the substance of anything but newspaper columns present itself in reality? Then what is the best way in which the substance can take on the form which will bring about the most appropriate human experience?

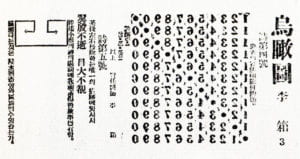

On deeper level, inquiry on the substance itself, the writing, should be thought of. What does the act of writing and the presence of written words mean? Typography, i.e., the presentation of thoughts in written words is not the only method that thoughts can actualize themselves. Notably, the act of speaking is another. In fact, historically, speaking was thought of as more direct and less distorted form of presentation of thoughts. Words and language is a Signifier of the hidden kernel, the substance, the thought. The Signified exist in our thoughts and the act of speaking spontaneously transforms such into a real object with a form through the Signifier that is the spoken words. In that sense, the written words are Signifiers of the Signifiers; the act of writing is signifying what was already signified. However, Jacques Derrida proved against this notion of the written words as something hierarchically lowered than the spoken words. He argued that we cannot ‘self-identify’ with the spoken words as much as we cannot with the written words and that there is no natural attachment to the act of speaking more so than the act of writing. In this sense, writing and speaking exist in parallel as ways of actualizing the substance, i.e., the thought, in reality. Here, we can reflect on the comparison we made during the class between the typography and rhetoric; how we choose typography is as important as how we voice our opinions in spoken words.

In this post, I wanted to see how I can approach a philosophic inquiry into the institution of typography. I think it shows that many questions on the choices we make in typography which, at least to me, sometimes felt arbitrary and flippant, can be grounded on philosophic foundation.