Hermann Zapf, his goal in his life was “to create beautiful letters,” one of his students was quoted saying (Weber, 2015). It is well known that Hermann Zapf is one of the most admired and important calligraphers in history, creating fonts that would serve as a guideline and inspiration for many fonts to come. However, Zapf had not always planned to be a calligrapher, he started out dreaming to be an electrical engineer.

The life of Hermann Zapf started in chaos. He was born into the German Revolution of 1918 – 1919 and the remnants of World War I. Unfortunately, misfortune did not end there, Zapf later found himself in widespread famine. Fortunately, the school that he was enrolled in and attended, provided meals. Much to his mother’s relief. It was there that Zapf found his interest the technical subjects of school. He found himself most intrigued by an annual science journal titled, Das neue Universum (“The New Universe”), At an early age, Zapf spent his days tinkering with electrical objects with his brother, building things like an alarm system for the house and a crystal radio. Even at this early age, Zapf had already started playing around with type, creating an alphabet in order to communicate with his brother in a secret language.

Though he initially wanted to be an electrical engineer, due to a new political regime, Zapf was unable to pursue this dream. Fortunately, his teachers had noticed his aptitude for drawing and advised him to try and become a lithographer. However, even this proved to be difficult for the adolescent Zapf because in each interview, he would be asked political question and though he was complimented on his work, he was ultimately rejected. He found his first job in 1934 as a photo retoucher and began his four-year apprenticeship. He became interested in typography through the works of Rudolf Koch and started to teach himself calligraphy through books. As a calligrapher his most popular works were Palatino, Optima, Zapfino and Zapf Dingbats.

Palatino was created in 1949 and is described as a detailed font where even “small details as the serifs were carefully scrutinized” (Hermann, 2016). It is an old-school serif font named after the gifted Italian writer, Giambattista Palatino.

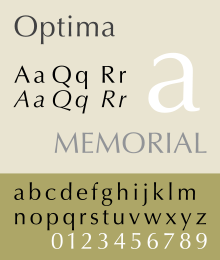

Optima is my personal favorite and is a beautifully designed, sans serif font which has such masterfully created variation in aperture that it almost hints at a serif. It was designed in 1952 and released in 1958. It was created after Zapf was inspired by the lettering on an old Italian grave during a vacation. It was inspired by the Romanic looking alphabet on this grave and was later developed to be more of a display typeface.

Zapfino is a complicated yet beautiful calligraphic typeface created to showcase the luxury and elegance that type is capable of displaying. It was initially designed in 1944 but due to limitations in type technology, it was released in 1998. One of the key aspects of Zapfino is that its lettering has multiple variations per glyph, each designed specially to complement its sister letters in specific compositions.

Finally, Zapf Dingbats is a collection of glyphs and symbols that were popularized when they were used by Apple printers.

(Image Sources: Wikipedia)

Though Hermann Zapf has passed, his legendary fonts continue to influence the development of type to this day. Many will continue to be inspired and guided by his expertise and practiced hand.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

History Graphic Design. “Hermann Zapf.” History of Graphic Design, 2018,

Weber, Bruce. “Hermann Zapf, 96, Dies; Designer Whose Letters Are Found

Everywhere.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 Dec. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2015/06/10/arts/design/hermann-zapf-96-dies-designer-whose-letters-are-found-everywhere.html.

Zapf, Hermann. “I’ve been asked to tell you about myself and my types” (PDF). Linotype.

Retrieved 26 March 2016.