Lettering is an art form that is constantly evolving and adapting. According to Jennie Cohen, the Roman alphabet was one of the first western hemisphere scripts recognized for its commercial use. It was traditionally written in the “print” form in which each letter was individual and had spaces between them, a great contrast to modern cursive in which each letter is connected to the other. By around the 5th century A.D., there were appearances of lowercase letters that connected together, much like how modern cursive does.

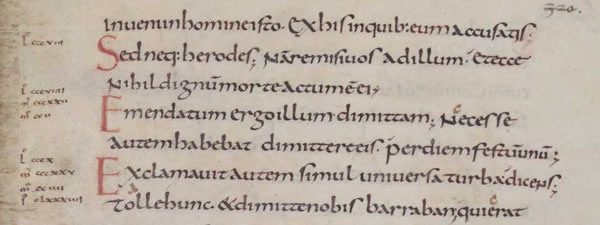

CAROLINGIAN MINISCULE

Source: Kualo. “Carolingian Minuscule.” Omniglot.com, 2019, www.omniglot.com/writing/carolingian.htm.

Soon there was the formalization of Carolingian minuscule by Charlemagne who had asked an English monk to create the typeface. Though it was not all connected, Carolingian minuscule had many connecting letters. In 1970, the typeface D’Nealian script was created and implemented in American classrooms in order to “ease the transition from print to a cursive typeface”(Cohen, 2012). In the 20th century, another writing style created by Charles Zaner and Elmer Bloser dominated elementary school classrooms.

D’NEALIAN SCRIPT

Source:https://schoolfonts.com/printnew/_CharSetDNCursive.gif

I clearly remember that when I was a kid, even as a homeschooler, it was part of our curriculum to have handwriting classes. Though I was first taught how to write in print, as I got older, my mother slowly started to introduce cursive writing to me. We were made to use books, worksheets, and homework to improve our writing. Even when writing our test answers or essays, we were made to write in cursive.

As I continued into high school and I was no longer made to write in cursive and I noticed that there was a significant drop in teenagers my age who used cursive to write. I too stopped writing in cursive and enjoyed the freedom to write in print. I was surprised to find that some people who had been able to write in cursive before, had forgotten how to write in the cursive form. Or alternatively, they would write in some hybrid of print and cursive. This, apparently, does not seem like an individual experience. A study of handwriting teachers showed that 37% wrote in cursive, only 8% wrote in print and 55% wrote in a hybrid of the two (Gladstone, 2103).

Recently, however, there has been an increase in the use of cursive again, not as a formal form of writing but as a decorative form. With the increase in popularity of diary decoration and bullet journaling. The youth are relearning how to write in the cursive for aesthetic’s sake. However, because it is now not used for a formal purpose, there has been a lot of variation in the use of script with alterations in the size, spacing, and alignment. Many contemporary artists are taking letters, making them their own and aestheticizing them as they wish.

Bibliography:

Cohen, Jennie. “A Brief History of Penmanship on National Handwriting Day.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 23 Jan. 2012, www.history.com/news/a-brief-history-of-penmanship-on-national-handwriting-day.

Gladstone, Kate. “Is Cursive Dead?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 Apr. 2013, www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/04/30/should-schools-require-children-to-learn-cursive/handwriting-matters-cursive-doesnt.