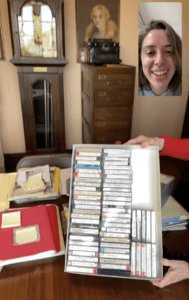

During the Spring 2021 semester, the RML project supported three interns from the NYU Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program. Each intern was hosted by an organization located on Long Island, which includes Suffolk, Nassau, Queens, and Kings counties. The following post is from Kayla Henry-Griffin, who interned at Los Herederos, a media arts non-profit organization.

For my Spring internship, I had the honor and opportunity to work with Los Herederos. Los Herederos (The Inheritors) is a media arts non-profit organization located in Queens committed to inheriting culture in the digital age and documenting the urban musical landscape in New York City. Los Herederos applies its mission by providing its production services to New York City immigrant communities and by preserving the myriad of cultures and traditions by making these documents accessible. In addition, Los Herederos have several ongoing projects which include the Sonicycle, Creative Masters, DREAMtellers Institute, and Inheritors (more information on these projects can be found at www.losherederos.org). Los Herederos also has an archive. I worked with the Urban Condors Collection, an archive of New York CIty’s Andean music scene.

I came into this internship with not much knowledge on Andean culture, let alone Andean music. However, I hoped to work with Los Herederos because I yearned to work with community archives that centered around BIPOC collections. What I have grown to understand about a collection like the Urban Condors Collection is that this collection is deeply rooted in the Andean community and communication with the community is essential to collect and preserve the heritage, whether that is preserving an Andean instrument, or preserving a born-digital MOV file of Inkarayku performing in a public space.

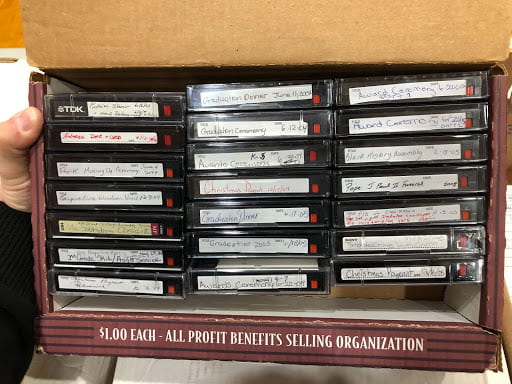

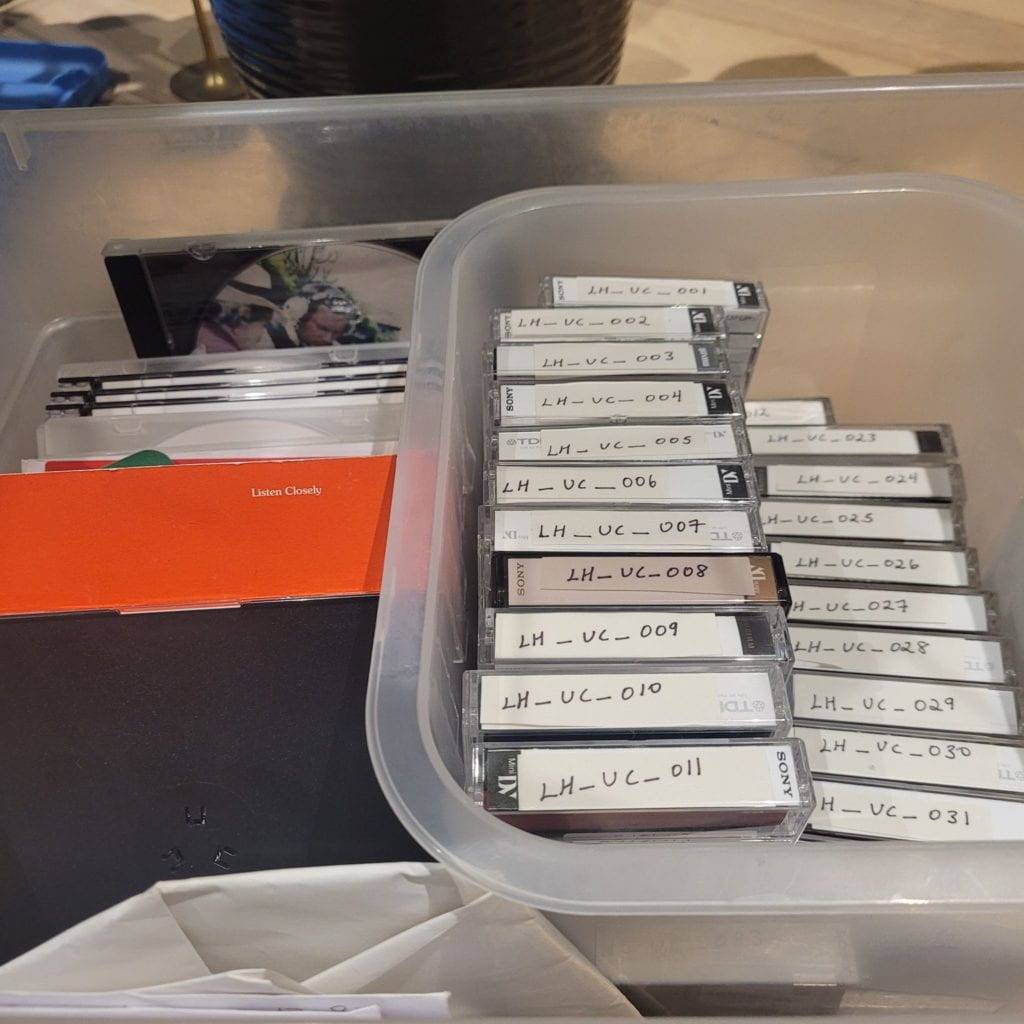

The Urban Condors Collection started as a graduate thesis research project conducted by Naomi Sturm during her time at Columbia University. Naomi studied Ethnomusicology during her time in Colombia and the Urban Condors Collection grew out of her thesis, “Urban Condors: Andean Music in NYC (1970-Present)”. Now, the Urban Condors Collection has a place within the non-profit organization. The collection represents the New York City Andean music scene, starting as early as the 1970s. The Urban Condors Collection includes the musical legacy of communities from Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, and Argentina. There are a few different formats such as MiniDV tapes (a magnetic tape format), optical discs (both CDs and DVDs), and born-digital files (files originating from a digital form). The multiple formats has to do with the fact that the content has been shot and reformatted throughout the years. Many of the optical discs hold older content that originated from MiniDVs and VHS tapes. These transfer refers to the antiquity of the Andean music bands in New York City.

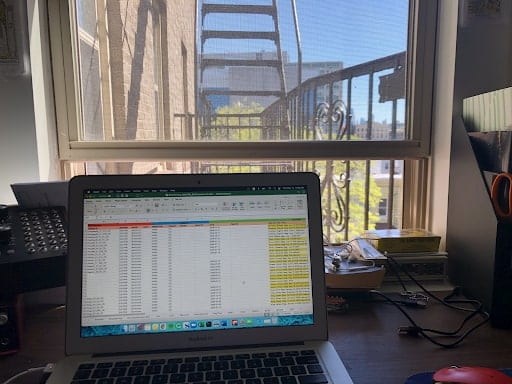

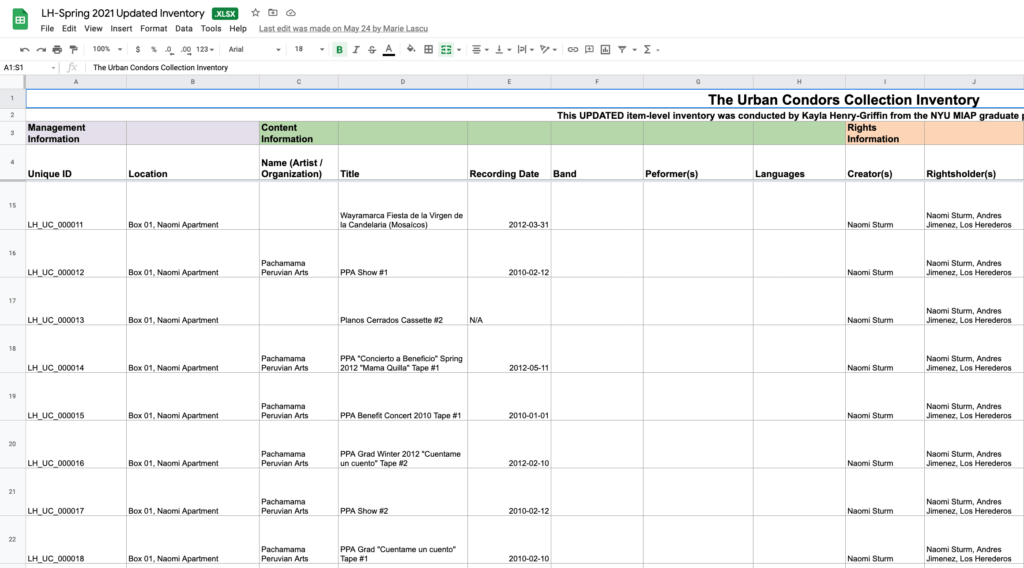

As a RML intern, my duties were to update the inventory spreadsheet and create a new collection assessment with new suggestions on how to preserve the Urban Condors Collection. The goal was to have a more updated and refined documentation of the collection for grant applications. Other than the name of the Andean band, dates and locations, I noticed that I could add more descriptive metadata fields that would refine the inventory. Descriptive metadata is considered descriptive information about specific content; an example of descriptive metadata is the recording date of the content. None of the labels or filenames described the band members or explained what the event was for. The process of updating the inventory led to a recognition and an awareness of how important it is to have a deep understanding of Andean music and Andean bands while cataloging such content. While adding new records to the inventory, I realized that I was lacking the knowledge of these Andean bands and I did not know anything about the band members.

For instance, much of the Urban Condors Collection holds performances by the band, Inkarayku. I did have knowledge of the current members of Inkarayku, but my internship supervisor and Executive Director of Los Herederos Naomi Sturm reminded me that Inkarayku band members change throughout the years. When playing back the Inkarayku band content, I was aware that I did not know everyone who was performing. I went back to Naomi to schedule a meeting with her to go over the content I played back so that she could identify the band members performing. This was not only helpful, but this process was essential for me to get a better understanding of Inkarayku as a band; sometimes, there will be all the members in one event, and then the next event it would only be a few of the members performing. I found it was important to record the names of the band members not only for honoring the members, but also so that researchers of this collection could discover more about the band starting from its inception. I had multiple conversations with Naomi to discuss the fields I wanted to include in the inventory (fields such as band, performers, and language). I found the conversations also assisted me in finding other missing metadata in the inventory.

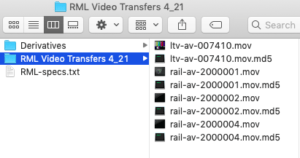

With this new knowledge, I was able to add more descriptive metadata that would be beneficial for those who wanted to access content in the Urban Condors Collection. I also found that having records of the band members would be honoring those band members who have contributed to Andean music in New York City. I was able to playback the optical discs and born-digital files in the collection. Playing back the content reminded me of the complexity of the process. My computer, like most computers these days, does not have a CD/DVD player, so getting access to an external player was necessary. Even with an external player, I had to be careful of what type I was using. Utilizing an external Mac DVD player, my computer was unable to read most optical discs in the collection. By switching the player to a more universal external player, I was able to play back all the optical discs in the collection. By playing back content, I was able to see the complexity of the band and I became more aware of the significance of these bands to Andean culture and music.

At the end of my internship, I reflected on all the work I had done. I completed a collection assessment and updated the inventory for the Urban Condors Collection. I also had the chance to create a key and a guide on how to add to the inventory as well. The key acts as a legend or a list of definitions that also holds controlled vocabularies that should be used for cataloging. But what I found to be equally important and essential is what knowledge I received from working with the collection and Los Herederos.

Working with a community archive has its challenges (such as the lack of equipment available to use), but there is so much rich information and content within the archive. The Urban Condors Collection holds very important performances from bands like Inkarayku and Wayra Marca and without documentation of these performances, future bands and artists may not see the brilliance of the Andean music scene in New York City.

What I took from this experience is a new philosophy and perspective on how to care for small archives, especially when they are primarily non-European cultures. I believe before working with a collection, I will commit to doing preliminary research on not only the collection, but the culture that it holds. I find that this practice not only expands my knowledge, but also this practice allows me to fully take care of the collection. I believe there is more to preservation than prioritizing the technical aspects of preservation. What is essential is the access to the collection, as well as knowing more about the culture and history of the collection. Without that knowledge, there will be missing pieces and the collection will not get the proper care and preservation that is needed.