Bioprospecting (also known as biodiversity prospecting)

My preconceptions of bioprospecting are rooted in a strong anti-capitalist cynicism – it is a horrible drain on the ecology of the Deep and will have lasting, irreversible effects on our environment in general.

Although much of what I am reading confirms this, that information is generally situated from the POV of environmental organizations. What I am beginning to uncover are articles written by biologists and vetted by science journals that puts the wholesale anti-bioprospecting stance into question for me.

(Note: I am momentarily suspending my belief that human-centric harvesting, husbandry, and consumption of non-human animal life needs serious re-evaluation.)

The use of sea creatures for medicinal uses has been practiced in China for over 600 centuries ( Hunt, Bob, and Vincent, Amanda C. J.”Scale and Sustainability of Marine Bioprospecting for Pharmaceuticals”). Marine animals such as turtles (for their shells), sea horses, and sharks (for their fins) are consumed for their healing or biologically balancing properties. In the case of shark fins, the consumption of “shark fin soup” is compounded by socio-economic implications due to its expense, preparation and presentation.

According to Bob Hunt and Amanda Vincent, there has been a marked rise in bioprospecting of Marine life due to recent discoveries of efficacy.

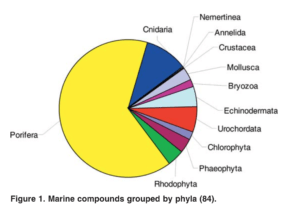

Marine species have become of increasing interest to bioprospectors for Western medicinals. Over 14 000 new chemical entities have been identified from marine sources (9), and at least 300 patents have been issued on marine natural products (10). The earliest known example of such exploration was the 1950s discovery of spongothymidine and spongouridine from the sponge, Tethya crypta, which led to the development of antiviral, anticancer, and anti-HIV drugs (4). Today, a new generation of marine-derived pharmaceuticals are set to enter the market. Examples include a chronic pain treatment, Prialt (ziconitide)—which is based on a peptide isolated from the cone shell, Conus magnus (11)—and the anticancer drug Yondelis (ecteinascidin 743), from the ascidian Ecteinascidia turbinata (12).

graph and citation: Hunt, Bob, and Vincent, Amanda C. J.”Scale and Sustainability of Marine Bioprospecting for Pharmaceuticals” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 35(2) : 57-64, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Research list:

Traditional knowledge and sustainability

Aquaculture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aquaculture

interest is growing in less explored ecosystems (eg. seas and oceans) and organisms (eg. myxobacteria, archaea)

Bioprospecting Oceans

https://sharkresearch.rsmas.miami.edu/drugs-from-the-deep-ocean-bioprospecting/

https://www.sintef.no/en/marine-biotechnology-and-bioprospecting/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-010-9879-9

https://chinadialogueocean.net/9644-high-seas-treaty-race-for-rights-to-oceans-genetic-resources/

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/blog/mariana-snailfish-tops-list-weirdest-deep-sea-creatures/

https://www.pnas.org/content/107/43/18318

list of animals: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0030580

other life-forms list: https://www.cbd.int/financial/bensharing/g-absseabed.pdf

“momentarily suspending my belief ” is the way to go into research, making sure there are divergent points of view, getting over the mental models we all have as we begin. GREAT research (and writing about it).