by Alex Thurston

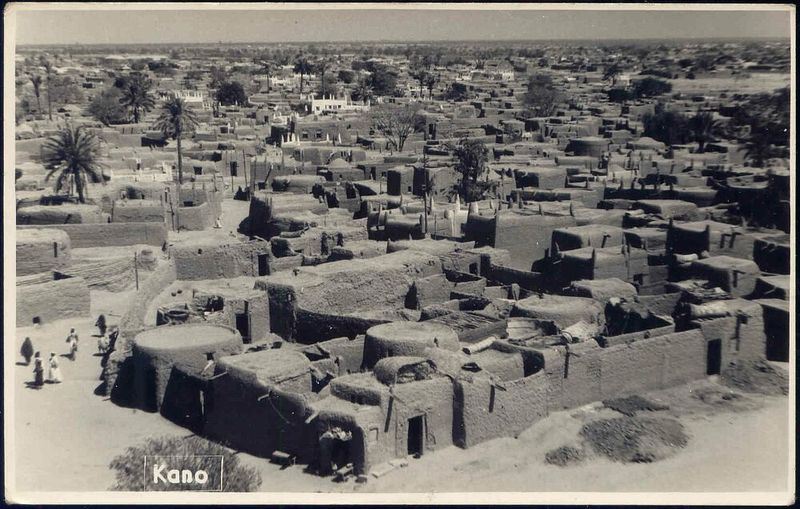

This post is the first of a series on Muslim schooling in Northern Nigeria.

Steady acts of violence carried out by Northern Nigeria’s rebel movement Boko Haram, whose name is often translated in the press as “Western education is forbidden,” has put issues of Muslim education in the region into the international news. Coverage of these issues has intensified with Boko Haram’s recent campaign of torching government schools in Maiduguri, the movement’s home base.

Boko Haram’s targets range well beyond schools – indeed, it has focused more on assassinating state security personnel, politicians, and rival religious leaders than on burning down schools. But the anti-schools campaign raises a set of questions about Muslim schooling in Northern Nigeria: What kinds of schools exist? How has schooling in the region changed over time? And what attitudes do Northern Muslims hold toward these different schools? These questions are critical for understanding Boko Haram but also, if one moves beyond headline-grabbing violence, for grasping more broadly what it means to be Muslim in Northern Nigeria, one of the largest Muslim communities in the world.

Schools are some of the main institutions where religious knowledge is shaped and transmitted and where attitudes toward society are formed. Schooling often stands as a powerful – and fiercely contested – symbol for community values. For Boko Haram, Western-style education seems to stand in for a whole complex of issues, including the perceived political dominance, corruption, and failure of Nigeria’s Western-educated elites. Other Northern Nigerian Muslims see Western-style schools as a pathway to future success for their children and transformation for Nigeria. Still others see Qur’anic schooling as an absolute necessity for forming moral Muslim children. Yet others send their children to hybrid “Islamiyya” schools, where students spend part of their time on religious studies, and part on subjects like English, science, and mathematics. Then again, some Northern Nigerian Muslims place their children in multiple different kinds of schools. All of these choices reflect different viewpoints about the spiritual and material value of schooling. Continue Reading →