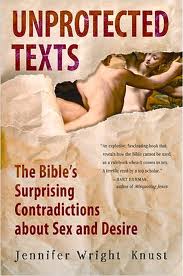

Unprotected Texts: The Bible’s Surprising Contradictions About Sex and Desire, by Jennifer Wright Knust (HarperOne, 2011)

by Natasja Sheriff

If you listen to the rhetoric of the more vocal proponents of conservative Christianity, you would be forgiven for believing that the Bible contains clear instruction on sexual conduct and morality. You might be less inclined to believe that the Good Book is actually full of hidden meaning and innuendo, erotic poetry, extra-marital seduction and love affairs between same-sex couples. Doesn’t the Bible teach that sex is for procreation, sanctioned only within the confines of marriage between two heterosexual adults?

No, says Jennifer Wright Knust, author of Unprotected Texts: The Bible’s Surprising Contradictions About Sex and Desire. An ordained Baptist minister and religious scholar with a doctorate in Religion from Columbia University, Knust knows what she’s talking about. The Bible, Knust argues, is not a sexual guidebook. It is inconsistent, contradictory, complex and, at times, “patently immoral.” “The Bible does not offer a systematic set of teachings or a single sexual code,” she says, “but it does reveal sometimes conflicting attempts on the part of people and groups to define sexual morality, and to do so in the name of God.”

Knust’s frustration is not with the Bible itself; instead, she’s annoyed by the people who claim to know exactly what the Bible is saying, who use it to dictate the lives of others based on their own narrow reading. “I’m tired of watching those who are supposed to care about the Bible reduce its stories and its teachings to slogans,” says Knust. Many of her conclusions are provocative and bound to attract the fury of the conservative Right. “Can the Bible be used to support premarital sex, even for girls? The answer, I have discovered, is yes.” She’s unlikely to find favor among the abstinence lobby. Yet she is not saying that the Bible promotes premarital sex, merely that it doesn’t present a consistent position on marriage, let alone sex within marriage. On this basis, finding a definitive answer to the question of the day—“Are you for or against gay marriage?”—is, frankly, impossible.

Written with her twelve-year-old self in mind, Knust recalls the shame and confusion she felt at being taunted and called a “slut” when she began a new school—everyone knew that sluts, like Jezebel in 2 Kings, deserve no less than to be thrown to the dogs. In Unprotected Texts, Knust’s philosophy is more in keeping with the message of love, compassion, and tolerance for which Jesus apparently stood, and less concerned with literal readings of the text. “No one should rejoice when Jezebel is eaten by dogs. Slavery is never acceptable, whatever the Bible says. And it is a tragedy, not a triumph, every time some young person somewhere is crushed by the weight of taunting and shame inspired by cruelty masquerading as righteousness.”

Knust is calling for a reevaluation of the way people think about the Bible and, in particular, the way many Christians misuse the Bible’s complex messages. She’s demanding that Christians take responsibility for their interpretations. In doing so, as a pastor, she is also giving the go-ahead to readers to explore the teachings of the Bible, readers who might have balked at the same analysis presented by a layperson. As Knust notes, some passages may support your point of view, while others don’t. With this in mind, she proceeds to present at length, and in meticulously researched detail, just how complex and ambiguous the Bible text can be.

The book provides a counter argument to some of the most hotly contested social issues in America today—most notably homosexuality. She tackles the issue from a number of different angles, drawing largely on the relationship between David and Jonathan, and the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, to dismantle the myth that homosexuality is a clearly defined sin. Challenging Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI), who in 1986 cited the story of Sodom as evidence that “there can be no doubt of the moral judgment made there against homosexual relations,” Sodom, as Knust shows, has very little to do with “sodomy,” as it is commonly understood in English. God rains fire down on Sodom not because the mob of Sodomites wanted to rape men, but because they wanted to rape angels. Knust argues that sex between angels and humans, not sex between men, is the ultimate sin. Elsewhere in the book, her discussion on homosexuality reveals both ambiguities in the Bible texts and contrasting historical and social contexts for the acceptance or rejection of homosexual relationships by biblical authors.

By and large, Knust seems to want the evidence to speak for itself. She succeeds in making a detailed case for each argument she puts forward, grappling with the complex messages and contradictions contained within the books of the Old and New Testament. It is a scholarly piece of work. But where Knust does not fully succeed is in translating her scholarship with clarity to a general readership. It is difficult at times to follow Knust’s analysis while also keeping in mind the numerous threads tying together a single theme across the Biblical canon.

Although she presents her case with the thoroughness of a scholar, some of Knust’s more subtle arguments, particularly where she draws on euphemism, may nonetheless fail to convince the more conservative reader. Notably in the story of Ruth and Boaz, she cites “the uncovering of feet” as a euphemism for either the uncovering of the genitals or the sex act itself. This happens to be an increasingly common reading of the text; Michael Coogan, for example, also offers this reading in his recent book God and Sex: What the Bible Really Says. Commenting on Knust’s Huffington Post interview with Stephen Prothero in February 2011, one reader sums up the likely response many people may have to such a conceptual reading of Biblical texts: “there is clearly no way a sound mind would interpret ‘uncovering his feet’ as anything related to sex.”

Unprotected Texts is a brave and fascinating book with a message that has broad social and political implications. By shedding light on some of the most enigmatic and emotive of the Bible stories, Knust inspires readers to engage with the Bible on a more personal level, and in doing so imparts courage to readers to question established doctrine. That said, the readers most likely to take up her message are those who are already open to a more progressive understanding of sexuality and human relationships as related in the Bible. Indeed, greater resistance to change is most likely to come from the very same people she is seeking to educate.

Natasja Sheriff is a journalist and graduate student at NYU’s Cultural Reporting and Criticism Program.