The Final Testament of The Holy Bible, by James Frey (Gagosian Gallery, 2011)

by Mara Einstein

With only a handful of shows left, Oprah has selected James Frey—yes, the same James Frey she publicly humiliated for “lying” in his memoir A Million Little Pieces (after making it a bestseller)—to be among the chosen few to get one of the most coveted slots in broadcasting. It turns out Oprah apologized to Mr. Frey in 2009, three years after publicly castigating him. (Am I the only one who missed it?) Seemingly, the two former feuders have been looking for a time to present the reconciliation more publicly, and with full Oprah Show fanfare it will happen before her last show airs on May 25th.

What makes this appearance particularly surprising is that the show will not only review what has occurred in Mr. Frey’s life over the last few years — he’s written some not-so-great books, co-authored a young adult book series, and tragically lost his 11-day-old son to a genetic neuromuscular disorder — the appearance will also, more importantly, promote his latest work, The Final Testament of the Holy Bible, perhaps the last book ever to be promoted by the woman who put publishing back in the black. From the title alone, this would seem like a slam dunk for Oprah, a woman who readily mentions Jesus and God on her daytime talk show (and has inspired endless commentary on her faith). However, what’s inside Frey’s book isn’t what one would expect from the outside.

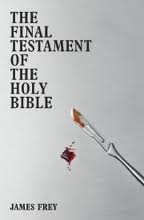

First, the outside: The Final Testament looks like a real Bible, something that Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science Church, famously did with Science and Health in 1875. For $150 you can buy a limited edition (1,000 copies), numbered copy signed by Frey. This high-end version of the book has a white leatherette cover and is housed in a white box with a simple design that bears only the title of the book and the name of the author, both in red lettering; For $50 you can purchase a limited edition that has a black cover with a gray box that, in addition to the title and author, has an image of an upended scalpel dripping red blood. Both are published by the Gagosian Gallery, known for presenting the works of prestigious artists such as Picasso, Calder and Lichtenstein. The choice of packaging and distribution suggest that the author is looking to appeal to an upscale audience; not only is the price point high but the only place you can buy the book in person is at the gallery’s bookstore on Madison and 77th, though a salesperson informed me that “clients” can also order the book online at Gagosian’s site.

Much as Mel Gibson released The Passion of the Christ on Ash Wednesday, a day when believers are thinking about, well, the Passion of Christ, Frey launched his book on Good Friday, another holy day on the Christian calendar that marks the Crucifixion. In Frey’s case, however, the strategy was less holy synergy than slap-in-the-face attitude. He’s not trying to appeal to Christians or people of faith generally. Rather, as Frey told the The Guardian, “I tried to write a radical book. I’m releasing it in a radical way.”

As to the content: The Final Testament is Frey’s vision of what would happen if Jesus came to New York today. Rather than the stereotypical soft, loving, smiling brother figure, Jesus is a former alcoholic and a pot smoker. He makes out with men and gets a prostitute pregnant. This book is meant to be provocative and perhaps even blasphemous. (The video promo posted on Amazon states, “James Frey is not like other writers. This book is not like other books.”)

Frey is certainly not the first to re-envision Jesus. Historian Stephen Prothero highlights the many ways people have created Jesus in their own image in his book American Jesus: How the son of God Became a National Icon (a premise that recalls Jaroslav Pelikan’s 1985 Jesus Through the Centuries). In a more closely related example Bruce Fairchild Barton, one of the founders of Madison Avenue advertising agency BBD&O, famously wrote The Man Nobody Knows in 1925. In it Barton envisions Jesus as a businessman as a way to make him more accessible to the growing number of people in corporate positions; Jesus is an “ad man” who, with the help of twelve other businessmen, sells “The Word.” At the time, it was considered controversial to present Jesus as an ordinary man—albeit a strong one and a good business man, but a man nonetheless. Initially, Barton had a hard time finding a publisher for the work but once published, it went on to become a bestseller. Frey appears to be trying to replicate this success, though less provocatively than the author might have hoped. Thus far, there has been no mass outcry, no protest by the religious right.

So, who was this marketing supposed to target? People that shop at Gagosian are upscale and presumably educated (and perhaps already acquainted with Frey who’s been writing art catalogue copy for the past few years). They are not going to be offended or possibly even notice that the timing of the launch and the content are interrelated. When I visited the gallery on the day the book first became available, if I hadn’t know about the book I would have walked right by it. There was no Barnes & Noble super-sized display with stacks of books as I entered the gallery. Rather, in the back of the shop, on the table where the cashier sits, there were six copies of the book—three of each edition—with an open copy of each so I could see what I was getting for my money. No signs in the window, no point-of-purchase displays. Nothing. It was startling given the outsized reputation of the author.

I contacted the gallery to ask about sales and marketing of the book but no one returned my query. I found some insight in an interview the author did with Newsweek. When asked why he did not go with a traditional publisher Frey was quoted as saying, “I wanted to make a really beautiful book. Something readers would be excited to own as an object.” Frey sees books, rightly I think, as becoming separated into two categories: upscale versions for people who want to own books as pieces of art and digital versions for those who are interested in reading them for content. Moreover, using Gagosian was also an obvious snub to the publishing industry that left him hanging in the wind after the first Oprah incident. Said Frey in the New York Post, “Never again will somebody release my work in a way that doesn’t make me comfortable.”

Frey is likely to be more comfortable when he starts generating significant revenue. This will occur, we can assume, through the sales of digital copies sold by the author and his literary agent WME (the former William Morris Agency). This is a particularly smart move – and perhaps a necessity for authors and publishers today — given that digital book sales surpassed paperback sales on Amazon this past January.

Reviews of the book thus far have been mixed. USA Today said, “No matter whether you believe or not, by the end of this boring, predictable book, you’ll feel you’ve suffered fiction’s version of the Stations of the Cross.” The review in The Guardian (UK) was entitled, “The Final Testament of the Holy Bible is shocking. Shockingly bad, that is.” The Financial Times, on the other hand, calls the work a masterpiece, “both a work of art and a bombshell hurled at the religious right.”

Whether trash for the masses or masterwork for the gallery crowd, The Final Testament will make for a very interesting discussion on Oprah’s couch and, no doubt, a Number One spot on bestseller lists.

Mara Einstein is associate professor of Media Studies at Queen College (CUNY) in New York and author of Brands of Faith: Marketing Religion in a Commercial Age (Routledge), named an Outstanding Academic Text for 2008. Einstein is a former marketing and advertising executive. COMPASSION INC.: CHARITY AND THE CORPORATE MARKETING OF MISFORTUNE is a critique of the ways in which charity is used as a promotional tool for corporate profits and will be published next year by University of California Press. She blogs about marketing religion at www.brandsoffaith.com.