by S. Brent Plate

I’m just back from a few weeks researching gardens in Japan, the kind of Zen-type designs that are most idealized in a place like Ryoan-ji. The wonderful thing about Japan, like so many contemporary places, is the ancient-modern juxtaposition that stares you down around every corner. You can walk out of the austerity of a 500-year old garden and in five minutes be at the local 7-11 skimming pages of the latest manga series. Which is somewhat what I did.

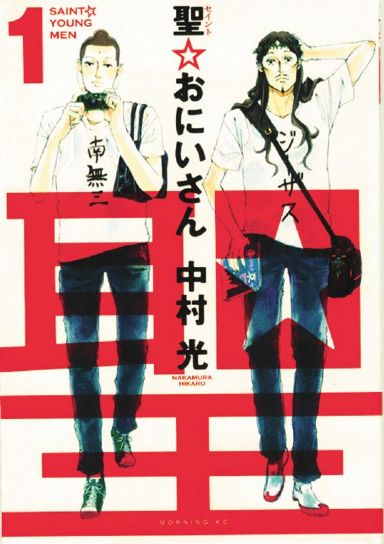

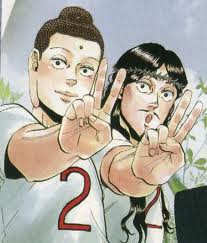

Along the way I stumbled upon the manga title Seinto oniisan, which usually gets translated into English as “Saint Young Men,” but also carries “brotherly” connotations. The brothers in question are none other than Jesus and Buddha, who take a vacation from otherworldly life to shack up together in the Tokyo suburb, Nachikawa. They share a spartan, tatami-clad flat, wonder over new technology, do their own laundry (mostly jeans and t-shirts with various Buddhist and Christian references), visit amusement parks, get their food from the local 7-11, and celebrate Christmas and Shinto festivals. The local school girls are attracted to Jesus because he looks so much like Johnny Depp, which makes him happy since people in the 21st century might actually like him; he comes off as a bit of a hippy slacker and wears his crown of thorns around like a bandana. The Buddha enjoys napping, usually sleeping in the pose of the great reclining Buddha, or downing a can of Sapporo beer in response to too much asceticism, while the young girls think he looks like Buddha and the Western tourists think he looks like a ninja.

The volumes are filled with hilarious iconic and verbal references to the mythical lives of the two figures who are trying to make sense of life in the twenty-first century. In a raffle, Buddha wins a life-sized sculpture of . . . the Buddha. Depressed, he murmurs, “I should have forbidden graven images.” And Jesus, who blogs about daytime television drama, is overcome with laughter at one point and his crown of thorns bursts into a garland of roses. In general, they hope no one really recognizes them.

The young artist Nakamura Hikaru, began publishing Seinto oniisan in 2006. It has become a bestselling manga in Japan for the past couple years. For her efforts on the series she won the “Short Work Prize” as part of the 13th annual “Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prizes” in 2009. Tezuka himself, it should be noted, was one of the leading figures in developing the manga form, and posthumously won Eisner Awards for his Buddha, published as an eight-volume manga telling the life of the Buddha. That series is currently being adapted to film and set to release in 2011. To complete the circle, Hikaru’s Seinto oniisan displays Jesus at one point reading through Tezuka’s Buddha, though Buddha complains that Jesus is flipping through the pages too fast!

(There is a useful online English translation (a “scanlation”) of early volumes done by “Megchan,” though a slight problem for English speakers here is that since written Japanese is read from right to left, so are comic book pages designed. When English translations are simply inserted into the speech balloons and the overall page layout stays the same, they have to be read from right frame to left. Its kind of like driving in Japan, you just have to switch directions, but it’s possible.)

While contemporary popular culture extols forms such as manga (manga makes up a large percent of the print industry in Japan) the word-image format has a long history on the island country, stretching back at least to medieval Buddhist storytelling pictures called etoki. Like the stained glass windows of medieval Christianity that were highlighted as the “bible of the illiterate,” etoki performances used paintings to reach an illiterate, lay audience. Buddhist monks and preachers used the images to explain stories of the Buddhist paradise (Pure Land) and great saints. They were, as Ikumi Kaminishi suggests in her book Explaining Pictures, “a form of medieval popular culture.” The difference of course is that etoki was enacted by Buddhist authorities for the promotion of Buddhism (and corresponding economic survival), while manga is generally created as artistic endeavor (and corresponding economic survival).

It will be interesting to see the responses if and when the series is repackaged for an English-speaking audience. Euro-Christians have already been plenty upset by comic images of Jesus Christ, from Austrian artist Gerhard Haderer’s comic The Life of Jesus (2002) which had the artist charged with blasphemy and demands for prison time by church authorities, to last year’s South Park portrayal. Undoubtedly, some would be upset (there are already some online religious reactions to Seinto oniisan), but many will simply enjoy it because, in the end, Hikaru has created an entertaining light-handed comedy. There are even some reports that Protestant and Catholic churches in Japan have distributed the series.

And for all those who have fretted over the Pew reports and Stephen Prothero’s writings that the United States is religiously illiterate, younger generations will be gaining more and more religious understanding through the mythologies found in video games, manga, anime, and other graphic comics. This is part of the argument made by Jolyon Baraka Thomas in a forthcoming book on the topic of manga, anime, and religion (University of Hawaii Press): While the historical accuracy may be suspect, these popular forms are indeed the teachers for a new generation. With or without significant intellectual and pedagogical attention to these media forms, new generations will learn religious histories in the pages of comics at the local convenience store. Which seems to me like a great place to start.

S. Brent Plate is visiting associate professor of religious studies at Hamilton College. His recent books include Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-Creation of the World; Blasphemy: Art that Offends. With Jolyon Mitchell he co-edited The Religion and Film Reader. He is co-founder and managing editor of Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art, and Belief.