By Laura McTighe, with Waheedah Shabazz-El and Faghmeda Miller

This article draws on a decade and a half of engaged organizing and research alongside Waheedah Shabazz-El and Faghmeda Miller, which we are in the process of turning into a book-length manuscript. Waheedah and Faghmeda are both Muslim women living with HIV. Each were diagnosed at dire moments in the AIDS epidemics in their respective countries––the United States for Waheedah and South Africa for Faghmeda. Both women have gone on to transform their personal struggles to access treatment, care, and support into public lives of meaning for thousands. As such, Waheedah and Faghmeda’s lives and work not only shed light on the complexities of resistance in the midst of extremis; their stories also illuminate the complex interplay between HIV vulnerability and forced removal, between Muslim women’s leadership and traditional religious authority, between public figures and private selves. In this essay, written in close collaboration with Waheedah and Faghmeda, I explore questions of women, religion, and activism through their lives and witness. I begin with the moment of their diagnoses, set amid the disassemblage of apartheid and the scale up of mass incarceration and develop––though our connections with one another––a portrait of the complex nexus of HIV, gender, Islam, and activism in the African diaspora between Philadelphia and Cape Town.

Faghmeda Miller did not get to vote in the first democratic elections in South Africa on April 27, 1994. That day, she boarded a plane to Malawi with her husband, Juneja. They had been married just days earlier in the Cape Flats neighborhood to which her family had been displaced under Apartheid’s Group Areas Act. The liberatory celebration of the rainbow nation touched Faghmeda personally: she was about to begin a life she had long imagined with a man she loved dearly. Those most intimate of freedom dreams, however, never materialized. Less than seven months later, on November 18, 1994, Faghmeda was made a widow. Her husband had died from what she would later learn was the steady deterioration of his immune system due to undiagnosed and untreated HIV.

About a month after the community gathered to make the janaza funeral prayers for Juneja, Faghmeda could tell that something was wrong with her health. Her parents insisted she fly back to Cape Town. When her health continued to deteriorate, she was admitted to the hospital and then released to her parents’ care for recovery on the

Faghmeda just after her diagnosis

(photo courtesy of Faghmeda Miller)

condition that she return in a month for a follow up visit. At that visit, the physician who admitted her was confused as to why Faghmeda’s health was still not rebounding. That physician called in colleagues for consultations. Those doctors one-by-one hovered over Faghmeda discussing her case as if she were not present. One took her blood. When Faghmeda asked why, the doctor did not answer. It was not until her admitting physician inquired that Faghmeda learned that her blood had been taken to do an HIV test. Two weeks later, her physician called her at home and insisted she come into the clinic. Stunned, with an HIV diagnosis in hand, Faghmeda’s mind turned to her late husband. Juneja went fast; Faghmeda assumed she would, as well. But she kept waking up, day after day, alive.

Across the Atlantic, the United States was a breeding ground for an epidemic of prisons. Amid the massive contraction of the neoliberal state, prisons had become a “spatial fix” for a people stripped of employment possibilities and welfare support. The population behind bars soared––about fourfold overall, but eightfold when just women were counted. In 2003, Waheedah had been caught up in a narcotic sting for a drug problem that itself had been the result of surviving an abusive relationship and having no social service support to help her heal. Legally, she was blamed both for the abuse and for the way she coped: six months in the Philadelphia Prison System was her state-ordered “treatment” plan.

That sentence removed her from the Philadelphia neighborhoods in which she had been born and raised––streets where she had found Islam through the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and his son Warith Deen Muhammad… streets she had also had to flee when she fled her abusive husband. That flight took her away from the Muslim community that was her safe haven and spiritual home. In the barracks of the women’s jail on the far northeast of the city, she found several Muslim sisters she had known back in the day and again took her shahada with them. Supported in this way, she began to advocate for other women inside, especially around health care, which was her chosen profession. In conversation with the city health workers, she agreed to take a free HIV test. Then, in a room with no curtains, she was given her results. HIV positive. Waheedah was crying and everyone was walking by. That day, Waheedah vowed she would tell no one. In truth, she willed herself to die. But she, too, kept waking up alive.

***

I first met Waheedah the day after she was released from prison. I was doing outreach with a new coalition of ACT UP and mental health activists dedicated to protecting the health of people behind the walls. Our call to action came after a series of deaths from medical neglect in the Philadelphia Prison System. We joined together in anger and through direct action to force independent oversight of the city’s prison’s operations. Once that was in place,we had to know where else to put pressure. And to do that, we had to know what was happening inside. We devised a simple outreach strategy: talk with family members before and after visits with their loved ones. There was only one bus that went to and from State Road where the sprawling prison complex was located, and it only came every twenty or thirty minutes. That gave us a lot of time to talk with families. Sometimes we also met people like Waheedah, who had been released directly from court by a judge and were on their way back up to the prison to retrieve their property.

Waheedah Shabazz-El

(photo courtesy of Waheedah Shabazz-El)

This story, like the vignettes of HIV diagnosis that open this essay, helps to put a point on an important distinction between HIV risk and vulnerability. While HIV risk is often measured in individual terms and by specific behaviors, thinking in terms of HIV vulnerability attunes us to the ways in which structural conditions impact health and wellbeing. Central to both Waheedah’s and Faghmeda’s stories of HIV infection are profound social and political ruptures from systems that trafficked in land dispossession and forced migration. In Faghmeda’s case, the Group Areas Act uprooted people from their homes and scattered them throughout constructed ghettos. In Waheedah’s, mass incarceration had precisely the same effect. What happens when people are removed from their communities? When social networks are disrupted? When resources are extracted? When services disappear? What do you do when no matter how hard you try the ends just never seem to meet?

Amid these profound social disruptions that drove vulnerability to HIV and a whole host of other health issues, the HIV epidemic was still too often understood in terms of individual risk and personal blame. Waheedah and Faghmeda both learned early on that the way you were supposed to tell your HIV story was to foreground the event of HIV diagnosis, not the life you lived before or after. Describing the moment of diagnosis put gut wrenching pain on display; it also separated the storyteller from her social context. The diagnosis story was a surrogate for the infection story. That is, it was a way for listeners to figure out without asking: “How did you get it?”––and also for storytellers to offer the proper scaffolding for that invasive question. In that moment, the observer could serve as judge and jury. Both Waheedah and Faghmeda knew that, and both were exceptionally well rehearsed at telling their respective stories. HIV infection was carefully sutured to the violations experienced in the moments of testing and diagnosis, to the complex and often contradictory layers of a life before, to the crippling pain in the wake of diagnosis, and to the curious fate of accepting (even willing) death while instead being given life.

Waheedah was a convert to Islam, who made the transition from the Nation of Islam to Sunni Islam during the Second Resurrection. Her addiction history carried shame within the Muslim community, as all consumption of alcohol and drugs has been prohibited through progressive revelation and centuries of legal argumentation. In her narration of her diagnosis story, Waheedah, thus, cast herself as a believer who had strayed and then returned. That return was dynamic. She retook her shahada in jail and immediately started mentoring other women in Islam. After her diagnosis, she kept all of her HIV literature in her Qur’an, because it was the one thing that no one would touch––out of respect for her and for Islam. Seeded in this narrative were small and great refusals of the stigma that was heaped onto her by people determined to let one blood test eclipse her decades of work before and after that event. There was also a no less forceful probing of her religious commitment.

Walking with Waheedah through her journey after release drove me to undertake training in Islam. That is how I met my teacher, South African Islamic Liberation Theologian, Farid Esack. While studying with Farid, I became acquainted with Faghmeda’s story of being the first Muslim woman anywhere to come out publically as living with HIV. I then traveled to Cape Town in 2015 to work with her in documenting her life and work. At face value, the contrast between Faghmeda’s and Waheedah’s stories could not be greater. Faghmeda was a self-described “shy woman” who was married amid the disassemblage of Apartheid governance. When she was given her HIV diagnosis, Faghmeda’s doctor pointed to her hijab in shock: How can devout Muslims contract HIV? The implication was that there was something that Faghmeda was not sharing about herself or her community. What was putting Muslim women at risk for HIV? In conversation, Waheedah, Faghmeda, and I began to ask what we could learn about gender, HIV, and Islam at the intersection of their stories.

***

“HIV is a curse from God.” That dictum has been repeated over and over again by the world’s religious leaders seeking to label and condemn entire communities on the basis of so-called disordered desire, be that from sex, sexuality, gender, or substance use. This one-for-one relationship between desire and God’s judgment is what led prominent Muslims like Malik Badri to double down in the wake of a global AIDS pandemic and claim that Islam itself was HIV prevention (a position Amina Wadud vehemently critiqued at the Second International Muslim Leaders’ Consultation on HIV/AIDS in 2002 and Farid Esack has worked to build a global theological response against).

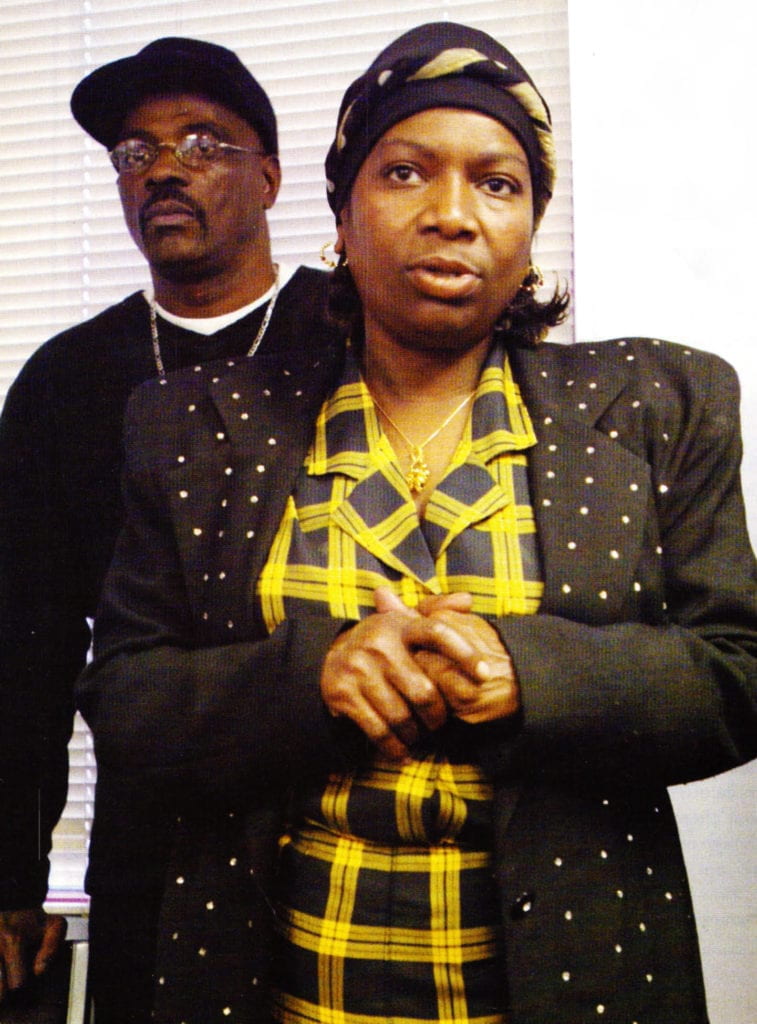

John Bell and Waheedah Shabazz-El

(photo courtesy of Laura McTighe)

The juxtaposition of supposedly being cursed by God and nonetheless continually waking up alive was theologically generative for Waheedah and Faghmeda both. How can you continue to be alive when God has cursed you? What does life even mean? What exactly is being condemned? Those questions were not meant to be answered in some hermetically sealed space of theological reflection. They were worn and reworn through the grooves of everyday life in which Waheedah and Faghmeda both had to figure out how to survive their diagnoses. Both went to the only places that they could find where people living with HIV were gathering. Faghmeda joined a support group run by Christians, because there was nothing of the kind in the Muslim community. Waheedah found her way to the gayborhood, and specifically to the inside/outside HIV in prison organizing program my dear comrade John Bell and I were running at the time.

There are things that become possible when the direct pressure of suffering relents, even just a little bit. When alone and terrified, Waheedah and Faghmeda both underscored how any support was soothing. However, when buttressed by support and coached through their darkest moments by people who had already fought those battles in Christian and gay communities, both Waheedah and Faghmeda began to imagine building the Muslim sisterhood they wish they had had when they were first diagnosed––sisterhood they still both desperately needed. To build that sisterhood, Waheedah and Faghmeda both had to publicly “come out” as women living with HIV.

There is something so profound about the will to expose one’s own pain so that others might feel less alone in theirs. And it is also is important not to romanticize the need to do so. For both Waheedah and Faghmeda, going public was born out of an everyday battle for survival. It was also a decision that would bring great personal and social cost––the more exceptional forms like becoming lightning rods for public shame and stigma, but also the more mundane ones like being expected to always be strong and to always carry so much. Nevertheless, a simple question undergirded both women’s brave work to render their suffering visible: When do we get to live and thrive, not just survive? That question pressed Waheedah and Faghmeda beyond the particularities of their own pain and into the structural contexts that prefigured their vulnerability to HIV.

***

After her release from the Philadelphia Prison System, Waheedah started doing work with our prison health care coalition to fix treatment and conditions for the women she had left behind and those she would never meet. She walked advocates who were not formerly incarcerated through the everyday context in which healthcare was delivered in the labyrinth up on State Road, helping us all to identify the links in the chain where possibility soared and injustice festered. With her guidance, the work of this Philadelphia County Coalition for Prison Health Care (PCCPHC) became a deliberate and willful process of nurturing the ties that save in order to sever those that kill. One of those life-giving and life-sustaining ties inside was “Dr. D,” the prison’s infectious disease specialist. She moved mountains for her patients, especially those who were newly diagnosed. And she did so with a keen sense of how to keep HIV status under wraps amid the always present systems of surveillance in which information was currency.

PCCPHC decided to present Dr. D with an award as part of an annual black AIDS luncheon––both to honor Dr. D’s work and to show her how many people on the outside had her back. Waheedah wanted to be the one to present that award, and she wanted to do so anonymously as a formerly incarcerated woman, not one of Dr. D’s former patients. The award ceremony was carefully curated. Waheedah spoke on behalf of the coalition and to a room filled with familiar faces and strangers alike. With a precision learned as a woman leader in the Nation of Islam and in tenant organizing battles, Waheedah indicted the health care inside and celebrated Dr. D as a soldier in the struggle. Her voice cracked. Looking into Dr. D’s eyes, award in hand, she turned to the audience and called her own bluff. “I cannot stand here like I don’t know this woman. My name is Waheedah Shabazz. I am a woman living with HIV. I was diagnosed in the Philadelphia Prison System in a room with no curtains. Dr. D saved my life.” Later, Waheedah would describe how she felt as “light as a feather” when the burden of that secret was lifted.

Fagmedha Miller recently (photo courtesy of Faghmeda Miller)

For Faghmeda, too, it was the community she found after diagnosis that paved the way for her public disclosure. At first, she told no one but the members of that Christian support group. Gradually, this community coached herthrough how to tell her parents. “You need to give them space and time to get used to this idea.” Her mother told her sisters and brothers, even though Faghmeda had asked her not to. It was terrifying in the moment, but, she says, it ended up being a blessing when her family worked through their fears together so that they could came together around her in unwavering support. By then it was the end of 1995; Faghmeda had survived her first year living with HIV. She started to reach beyond herself, to wonder what this life would be.

About a month before World AIDS Day 1996, her Christian support group held a public gathering. Faghmeda’s parents came with her. A member of the Islamic Medical Association, Ashraf Mohammed, was also in attendance and approached Faghmeda’s father. In a brief exchange, Faghmeda’s father’s explained that he was in attendance to support his daughter. Faghmeda was standing near her father and listened carefully while Ashraf explained his desire to host a World AIDS Day segment on Cape Town Islamic station, Radio 786.

After the event, Faghmeda discussed going on the radio show with her parents and then with her siblings. Every Muslim in Cape Town listened to that program, including her extended family members. To go on the air would mean disclosing her diagnosis to her entire community; the weight of not speaking openly was starting to tear at her insides. And so, the week of the show, Faghmeda decided she would go on the air to talk about Islam, AIDS, and herself. She was terrified the moment her scripted portion stopped and the phone lines opened. But then people started calling in, sharing their experiences with family members who died from AIDS-related illness and how much pain it still caused them when they thought about the stigma these family members endured… Faghmeda was blown away by the outpouring of support from her community, and also extremely hurt that none of her own family members had called in. When she walked out of the recording booth, her mother was sitting in the lounge. She hugged her tightly. That evening, Faghmeda cried about having HIV for the first time

***

These moments of disclosure laid bare the precarious and nonetheless durable intimacies through which worlds

otherwise could grow––worlds in which it might be possible to live and thrive, not just survive. What would happen if relationships like Waheedah’s and Dr. D’s were able to take root and come into bloom? What if the fleeting exchanges between Faghmeda and radio show callers-in could be extended into the everyday lives of families, communities, and the nation? How did the work to nurture the ties that save help sever those that kill?

Refusing to vanish is bone-deep, religious work. As Waheedah explained, “For me, it all ends up on that day, when I have to account for what I did in this life. I want to be able to account that I praised God, that I worshipped God, that these are the things that I did.” By rendering visible the complexities of HIV and gender injustice and daring to build community otherwise, Waheedah and Faghmeda understand themselves to be embodying the most fundamental ethical principle in Islam: the obligation to command good and forbid evil.

How did this slow and steady work of two Muslim women living with HIV bring into being new horizons for being and belonging together? What new meanings of Islam, gender, and AIDS were being made in the process? Faghmeda could see the ripples of their work on the greatest and most intimate scales. “We are both Muslim women, we are both African, we have been oppressed by our own religion. And the fact that we were actually given a platform? Yes, we were rejected by some people, but we continued to talk about what matters most to us and that is HIV and AIDS… Many of our people still believe as women, you don’t have a voice. But we know better. We do have a voice and we are making use of that voice.”

***

Laura McTighe is a postdoctoral fellow in the Society of Fellows at Dartmouth and the co-founder and associate director of Front Porch Research Strategy in New Orleans. She comes to her work in the academy though twenty years of grassroots organizing in movements to end AIDS and prisons. Through collaborative ethnographic methods, her research centers the often-hidden histories, practices, and geographies of struggle in America’s zones of abandonment, and ask how visions for living otherwise become actionable. Her current book project, Born In Flames, is a collaborative ethnography of race, religion, and the spatiality of opposition in post-Katrina New Orleans, which she has researched and is writing alongside the leaders of Women With A Vision (WWAV), a Black feminist health collective founded in 1989. She is also completing a second book-length project, Refusing to Vanish, on Muslim women’s AIDS organizing in the African diaspora, of which this article for The Revealer is a part. Her next major project, “Moral Medicine,” a historical ethnography of the women’s carceral sphere.

Faghmeda Miller was born and raised in Cape Town, and was the first Muslim woman in South Africa to have publicly disclosed her HIV status in 1996. Faghmeda is currently working as a Health Promoter at the University of the Western Cape, managing the Care & Support group. She is involved in HIV & AIDS awareness programs both on campus and in the broader community. Faghmeda has done several television programs locally and internationally, and appeared in various magazines, newspapers, documentaries and on radio stations in Cape Town and Johannesburg. Faghmeda’s documentary “The Malawian kiss” tells her story, and shares how she continues to educate others about the virus. In 2000 Faghmeda received the Femina “Women of Courage” Award and was nominated for “Women that made difference” in their community. Faghmeda’s message to newly diagnosed HIV positive people, “HIV is not curable but it is manageable therefore do not think it is the end, rather see it as the beginning of a new life, don’t give up, persevere”.

Waheedah Shabazz-El, an African American Muslim woman and retired postal worker was diagnosed with AIDS in 2003. Waheedah is a founding member and currently the Organizing Director for Positive Women’s Network-USA. Waheedah is a Steering Committee Member for HIV Prevention Justice Alliance, Board Member for Pennsylvania AIDS Law Project and Goodwill Ambassador for Philadelphia FIGHT. In July 2010 Waheedah delivered the closing Plenary Address at the International AIDS Conference in Vienna Austria. Waheedah has been the recipient of countless awards noting her commitment to AIDS Activism and Human Rights, including an invitation to the White House announcement of the National HIV AIDS Strategy where she met President Barak Obama.