By Kevin Healey

This past summer, on a whim, I grabbed a copy of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther off the shelf at the local municipal swap shop, reading it in short thirty-minute bedtime bursts on warm, open-window nights. Written in diary form, the novel lends itself to a-bit-at-a-time reading. I suspected from the start that it might dovetail nicely with my long-time appreciation of Morrissey’s romantic, melodramatic lyrical and vocal style.

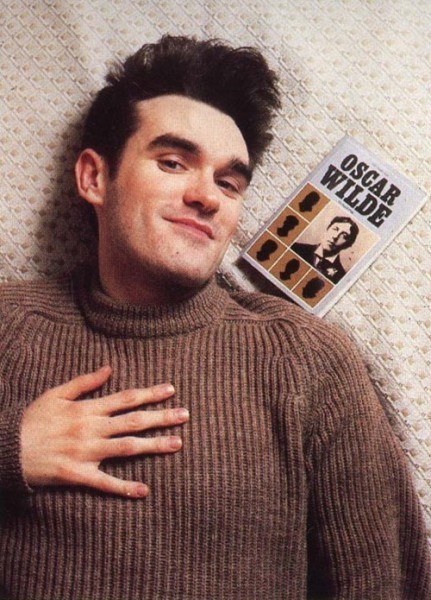

In a sense, it did. After all, is the latter not the late-twentieth and twenty-first century version of the pitiful young Werther, whose “pashernate” love remains unrequited and/or forbidden? And isn’t it clear that Morrissey half-imagines himself as a high-minded Goethe or Wilde, hell-bent on elevating the pop-culture vocabulary of the masses, whether they like it or not?

Having read his Autobiography, I had high expectations for List of the Lost when its publication was announced. Those who have read the former volume will recall that, about half-way through, the author provides a detailed description of his, and his friends’, drive-by encounter with the “specter” of a young, half-naked man in the dense fog of Saddleworth Moor:

Having read his Autobiography, I had high expectations for List of the Lost when its publication was announced. Those who have read the former volume will recall that, about half-way through, the author provides a detailed description of his, and his friends’, drive-by encounter with the “specter” of a young, half-naked man in the dense fog of Saddleworth Moor:

James recoils from the passenger door where, just beyond, stood this wretched vision of sallow cheeks and shoulder-length hair, a boy of roughly 18 years wearing only a humiliatingly short anorak coat that was open to expose the white of his chest and the nakedness of the rest of his body. The vision chilled our blood as the boy threw out his arms in a forsaken Christ-like appeal. Zooming away, and with him now lost in the dark, our talk is a clutter of “What WAS it?” and “Jesus, what…?” and “How could ANY being be alive out here?”

At the time, I was reminded of my half-hearted high-school readings of “The Tell-Tale Heart” or “The Pit and the Pendulum.” As an unexpected but satisfying detour, that passage struck me as the highlight of Autobiography, and I wanted more.

List of the Lost shows that Moz has much more up his sleeve in terms of suspenseful, and supernaturally disturbing, storytelling. This should not be surprising to anyone who has been listening to him for the past several decades: impassioned Ouija board pleas to the deceased, prayerful “Dear God” petitions, and speculations about “another world” beyond this “loneliest planet” dot every turn of his career. The new novel adds to that mix what the author calls “demonology” and “the left-handed path of black magic.”

In summary, the book traces the aftermath of four young track stars’ accidental murder of a lone wretch whom they encounter in the woods. Ezra, Nails, Harri, and Justy are subsequently haunted by the ghost of a mother whose child was raped and murdered. In the course of their attempts to uncover the boy’s remains and hold his murderer accountable, they are beset by tragedy after tragedy: suicide, murder, death, and the demonic return of the very wretch whom they had killed. In terms of direct inspiration for the novel, Morrissey may tip his hand when he has Ezra pronounce, teary-eyed and haunted by death: “Edgar Allen Poe couldn’t concoct this.”

That brief quip may, in the eyes of critics, simply reinforce the notion that Morrissey is narcissistic and self-aggrandizing. But even as he aspires to a similar prose style, List of the Lost addresses sexuality, religion, humor and death in ways that no nineteenth-century author could have. To be sure, Wilde’s sharp wit echoes in the self-conscious rants of Mr. Rims; Goethe’s passionate melodrama resounds in Ezra’s desperate pleas to Eliza; and Poe’s imagery saturates the passage in which Ezra encounters “a shrunken and concave visualization that looked as if released from her own grave.” But Victorian repression has since taken different, though no less lamentable, forms. Morrissey chose to set his novel in 1975, the year in which Ronald Reagan first ran for President and Margaret Thatcher emerged as Leader of the Conservative Party. Repression indeed—of a political, sexual, and economic sort that neither young Werther, nor one of Poe’s unnamed narrators, could have imagined.

In the author’s estimation, it seems, we have not yet turned the page on the shameful and hateful legacy of those conservative icons whose policies and personalities haunt us still. But perhaps we can understand the nature of our fate today by asking our deepest questions while looking back at that pivotal time. Thus the detailed stories of “our four favored athletes” are interspersed with tangential commentaries in which Morrissey engages the reader on topical issues from the environment to mass media and politics. The boys’ trip to the aptly-named Natura collegiate retreat, for example, serves as a platform for current-day musings on the importance of human respect for the natural environment. “Nature always waits in the wings and the winds,” Morrissey writes in his own voice, “ready to pounce with all of its power just at that sloppily contented hour when you foolishly assume

it to be plainly tired out.” Toward the story’s end, he describes Reagan’s entrance into the Presidential race as “an ideal antidote to everything now visible on the streets of America” before slyly segueing into a gender deconstruction of the then-popular television show Bonanza. As if to stave off further suggestions that his imagery often verges on the misogynous (an accusation leveled against songs from “Pretty Girls Make Graves” to “Kick the Bride Down the Aisle”), he voices his long-standing critique of Thatcher through Ezra’s girlfriend Eliza, who (perhaps ironically) describes the politician as “a token woman” who “just can’t wait to be one of the boys.”

In the end, though, these asides take a back seat to the primary issues that have always preoccupied Morrissey: sex, God, and morality. The pointed questions he asks the reader in List of the Lost (“What is this terrible, terrible world? And how are we expected to behave in it?”) are continuations of questions he has posed for decades in his lyrics, and with similar exasperation: “Does the body rule the mind, or does the mind rule the body?” “Is evil just something you are, or something you do?” “Are you aware, wherever you are, that you have just died?” He is, justifiably, obsessed with such questions, yet always at a loss. “I dunno,” he answered himself years ago, and does so again, implicitly, in List of the Lost.

It may be that combination of sincere inquiry and willful agnosticism that leads him, like Poe before him, to write in the first-person voice of someone known to “do” evil. In one of his finest vocal performances, “It’s Not Your Birthday Anymore,” Morrissey tells a story of sexual abuse through the eyes of the abuser. One can almost hear that same strained crescendo-falsetto as a similar scene is reconstructed in List of the Lost in which the desperate ghost-mother recounts her boy’s murder at the hands of Dean Isaac—who still presides over the affairs of the institution where the story’s main characters attend school. Morrissey empathizes first and foremost with the victim, drawing clear parallels between the abuse and murder of the child, Noah Barbelo, and the slaughter of animals (the latter being the gravest of sins, in the author’s moral ecology):

The bloodbath boy lay back, like sheep, like pigs, like slaughterhouse bulls, cut into ribbons by the thrill-kill human race who are nothing without butchery and hatchets and vindictive cruelty.

At the same time, though, the apparently “evil” figures in List of the Lost (including the “elderly imp” whom the boys fatefully encounter in the forest; and Dean Isaac, the child-murderer) often make comments in their long-winded rants that sound remarkably like Morrissey’s own confessional lyrics, or something he might have written in a spur-of-the-moment post to True-to-You.net—condemnations of police brutality, religious hypocrisy, sexual and racial prejudice, and the pretensions of wealth, to name a few. What should we make of the similarity between the elderly imp’s confession that “a girl laughed at me when we were thirteen… and it  triggered my dislike of all women” and Morrissey’s own sexual coming-of-age tales on The Smiths’ first album, where he cries, “I look at yours, you laugh at mine, and love is just a miserable lie”? What should we make of the fact that, despite the efforts of Nails and Justy, Dean Isaac’s life is ultimately spared? Is Isaac’s name a Biblical allusion, and if so of what twisted sort exactly?

triggered my dislike of all women” and Morrissey’s own sexual coming-of-age tales on The Smiths’ first album, where he cries, “I look at yours, you laugh at mine, and love is just a miserable lie”? What should we make of the fact that, despite the efforts of Nails and Justy, Dean Isaac’s life is ultimately spared? Is Isaac’s name a Biblical allusion, and if so of what twisted sort exactly?

I dunno.

While many of Morrissey’s questions to the reader remain unanswered (not to mention the reader’s own) there is nevertheless a clear theme that emerges in List of the Lost: namely that the depth of personal tragedy one encounters is a measure of how thoroughly one’s quest for an authentic life has been thwarted—either through self-denial, religiously-inspired prejudice, social convention, or some combination of each. The most likely scenario, apparently, is a death-spiral of tragedy upon tragedy. But the twin trophies of authenticity and integrity glimmer still, if only in the far distance. Morrissey has chased them from the beginning, with track-and-field determination, and his persistence is what has made him a cult icon. His legions follow in his quick steps, hoping to catch one carefully measured word as he passes them on, baton-like, to loyalists and hangers-on.

It is, of course, loyal fans who will most appreciate List of the Lost—which brings me to a final note about the novel’s style: if you are thinking about picking it up with the same last-minute thoughtlessness that you might snatch Dan Brown’s latest from the grocery-store checkout, think again. Morrissey’s prose is challenging. He has no use for throw-away sentences. Form towers mightily over function in terms of aesthetic priority. Why serve up the prose equivalent of Bud Light if you are fully capable (or at least hopeful) of producing a fine Chianti? Aside from a few bits of dialogue, there are nearly zero sentences that could easily be snatched up and dropped indistinguishably into another author’s work. Every phrase and word choice is distinct, as if the author were crafting the written version of a “smash-able” brand.

This approach, incidentally, is equally present in his Autobiography. As if released from the time-trap of the three- or four-minute pop song, in both volumes he stretches out and wraps himself in the sheer pleasure of wordplay and clever syntax. Flying in the face of a Twitter-induced trend toward succinctness and brevity, one sentence might linger on for what seems like days, as if daring any junior-high English instructor to diagram it properly. Consider, for example, how he describes the after-hours atmosphere of Priorswood campus, where Ezra first encounters the distraught mother’s ghost:

Now, with midnight minutes away, Ezra sat in the eerie silence of a college with no afterlife when unoccupied, and it dies a fast execution without its busy and odorous humans, as a subterranean hush washes through the halls and the building simply cannot live. At nighttime the rooms are spirited away, unable to manage convincing sleep, unable to be anything at all minus its sludgeball students, as life leaves its old soul—as if these bricks and glass thrive only on human blood, and graveyard corridors sob softly with the despair at having no use once the pock-faced pygmies have gone to their homes to moan.

Of course, in writing this way he confirms all of the reasons that his fans love him (unrepentant idiosyncrasy, lack of regard for convention), and all of the reasons that his critics most decidedly do not (self-interestedness, pompousness). But then, it was never his goal to appease the muddled masses. Though challenging, his approach is at least consistent, and once the reader becomes familiar with it the pages will turn themselves in anticipation of whatever wit or shock might come next. In the end, the patient reader is left not with the knee-jerk critique that the author’s word choice is opaque and his sentences too long; but that the novel is frustratingly—almost teasingly—too short. Call me a masochist (a Moz-ochist?) but I, for one, hope to hear that another is forthcoming.

***

Kevin Healey is an Assistant Professor of Media Studies at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. An alumnus of the late-1990s tech bubble in Silicon Alley, Kevin’s research focuses on media, religion, and digital culture. His work appears in Journal of Mass Media Ethics, Symbolic Interaction, Cultural Studies/Critical Methodologies, and Nomos Journal. He is the co-editor, with Robert H. Woods, Jr. of Prophetic Critique and Popular Media, published in 2013 by Peter Lang.