Sudanese flag logo, www.sudanrevolts.wordpress.com.

Track events in Sudan on Twitter with #SudanRevolts

by Alex Thurston

Why is the international media ignoring the anti-regime protests in Sudan? the blogger and international development consultant Mohamed el Dahshan asks at Foreign Policy. The protests began on June 16, triggered by the government’s announcement of austerity measures including higher taxes and cuts to fuel subsidies. The demonstrations (complete with barricades, teargas, rubber and actual bullets, arrests, beatings, deportations, and savvy social media activism) quickly escalated into demands for greater social and economic rights and the ouster of President Omar al Bashir, who took power in a coup in 1989. The protests have also spread well beyond Khartoum. The government has responded with a violent crackdown. As el Dahshan notes, “the headlines ought to write themselves.”

El Dahshan believes the media’s relative disinterest in the protests is linked to a conceptual problem. He writes, “For the past two decades at least, the international media has chosen to designate Sudan’s people as global villains.” The Sudanese were seen as villains in the civil war with South Sudan, and as genocidal killers in Darfur. “Now the journalists are finding it impossible to backtrack on that position and hail the Sudanese as normal people aspiring for a better life.”

I agree with el Dahshan that conceptual blinders make it difficult for the media to cover the protests – although in fairness to the media, there has been some coverage, just not at the near-obsessive level that characterized attention to the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. I would add two other conceptual issues to the idea of “bad Sudanese.” First, the idea of “Arab spring” is flawed in ways that make it difficult to understand Sudan through that lens. And second, media narratives about the Arab world are currently focused on issues related to Islam and politics – a narrative that has trouble describing the complexities of Islam in Sudanese politics, where (ostensible) Islamists already hold power and plural Islamic identities coexist in the political arena.

Some of the problems with the concept “Arab spring” are well known. The Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions began in winter, not spring, and in any case that was a year ago. Do Sudan’s protests belong to an extended spring that began in 2011, or are they part of a new spring? It makes no sense. Next, the “Arab spring” media concept took its starting point with the Tunisian and Egyptian cases, and it’s been difficult to apply the model to other countries with widely varying contexts and outcomes. While “Arab spring” has expanded to include cases of civil war (Libya and Syria), the media has had a harder time with cases where protesters could not topple the government (Bahrain), where the protests brought only a cosmetic change of leadership (Yemen), and where the media wanted a revolution to occur but it did not (Algeria).

There has also been a geographical bias in coverage of the “Arab spring.” Sudan and Mauritania have the misfortune of lying too far south for the media to take them seriously as Arab countries (though the category “arab” is an active social and political one in both countries), and too far north for the media to get excited about an “African spring.” Both Sudan and Mauritania are seen as geopolitically peripheral. (This perception holds partly true as far as their political influence and clout is concerned, but it has removed two crucial cases from the search for patterns in the Arab uprisings.) If Sudan’s protests have been ignored, the serious protests in Mauritania have been doubly so. Should Sudan’s protesters topple President Omar al Bashir, I believe the media would get excited, but until they do, the Sudanese will remain, for the media, “marginal Arabs” or, as el Dahshan argues, Arab “villains.”

Then there is the issue of Islam. Much media coverage of the Arab world has focused lately on how the Arab spring affects the relationship between Islam and politics in the region. What will the Muslim Brotherhood do in Egypt? How have Islamists fared in Libya’s elections? Who in the world are “Salafis”? Is Al Qaeda benefiting from the Arab spring? And on and on. But in Sudan, Islamists already wield power. The protests, meanwhile, have mobilized different forms of Islamic identity, but these identities often seem too complex to be rendered in news media. The media have particular trouble with leaders whose religious and political authority stems from multiple sources.

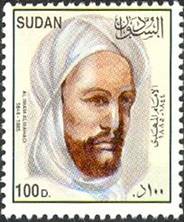

Sudanese postage stamp depicting Mohamed Ahmed (the Mahdi), who led the successful 1885 Sudanese revolt against British and Egyptian rule. (Source: Michael Kevane, African Studies Quarterly, Spring 2008).

How, for example, should the media describe Sadiq al Mahdi, who has offered some support to the protests? Is this support significant because he is a leading opposition politician? Because he was prime minister of Sudan when Bashir took power? Or because he is the great-grandson of the Mahdi, an Islamic leader (Islamist?!) who drove the British from Sudan in 1885 and established a short-lived Islamic state? Or because members of the Mahdiyya (the Mahdi’s community) still view Sadiq al Mahdi as a spiritual leader? His support for the protests is significant because of all of these factors, but outlining each factor’s salience – and how it interacts with the others – is only a starting point in discussing the various Islamic tendencies that overlap and compete within Sudanese politics. Most reports don’t have the space to delve into such issues, and perhaps audiences aren’t much interested to begin with. And so the position of Islam in Sudanese politics does not fit easily into narratives like, “What if the Islamists come to power?” or “Islamists are hijacking a secularist movement” or “Haha, the Islamists didn’t do as well as they wanted in those elections.”

Amid the relative lack of media interest, Sudan’s protests (and the resulting crackdown) have continued for three weeks, and look set to keep going, though protesters face an uphill battle in ousting Bashir. Until they can come closer to doing so, the protesters will also have trouble getting sustained attention from the international media, though Twitter, other social media, and commentary like el Dahshan’s certainly brings a level of attention. Finally, as el Dahshan and Amir Ahmad Nasir have pointed out, media coverage is not just about bringing attention to the protests, it could also be a factor in their success or failure. The media cannot pick winners and losers in Arab streets, but their choices have political consequences there.

Alex Thurston is a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Northwestern University. For 2011-2012, he is conducting dissertation fieldwork in Northern Nigeria. Alex has written for the Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, and The Guardian. He blogs at http://sahelblog.wordpress.com, and is a regular contributor to The Revealer.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.