By Laura McTighe

This is the fourth in an ongoing series of articles that Laura McTighe is writing for The Revealer about issues at the intersection of race and religion. She will be writing about incarceration, activism and organizing, reproductive justice, and more, with an eye to questions of history, violence, and justice. You can find the previous three articles in this series here.

***

Author’s Note: In the last two weeks, our national conversation about race has moved from the absurd interrogation of Black womanhood because a white woman donned blackface, to the calculated massacre of Susie Jackson, Ethel Lance, Clementa Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Cynthia Hurd, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Depyane Middleton Doctor, Daniel Simmons and Myra Thompson under the guise of protecting white women’s purity. The #NotInOurNames hashtag has emerged as an affirmation that white people will not be complicit in racist terrorism any longer. Black women started us chanting and tweeting #BlackLivesMatter. If we are going to realize their vision, we must learn to embrace the leadership they have been providing for centuries – and we must confront the ways in which when we have unwittingly and willfully erased their work.

***

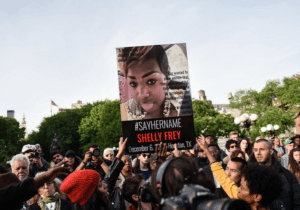

#SayHerName vigil in Union Square, New York on May 20, 2015. Photo: Andy Katz/ Corbis via For Harriet

“All that you touch You Change. All that you Change Changes you. The only lasting truth Is Change. God Is Change.” In the Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler breathed to life a new religion – Earthseed – based not in the sacred scriptures of elders and prophetic pasts, but in the presents and possible futures of the living. In accepting that God Is Change, believers were called to stand in their own power, to shape themselves, to shape the universe, to shape God. “Why is the universe? To shape God. Why is God? To shape the universe.”

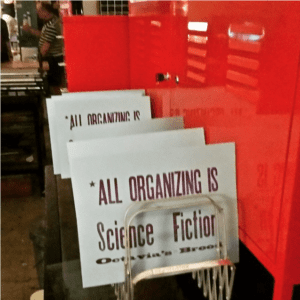

My reintroduction to Octavia Butler came from Walidah Imarisha at a conference I co-organized with Josef Sorett last Fall, Are the Gods Afraid of Black Sexuality?: Religion and the Burdens of Black Sexual Politics. At the conference, Imarisha introduced us to the idea of “visionary fiction” that she and her co-editor, adrienne maree brown, had employed in their newly published anthology, Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements. As Imarisha explained, “Visionary fiction is not neutral. It does not purport to be neutral. The goal of visionary fiction is to create social change. All organizing is science fiction.”

It’s a jarring idea to bend your mind around. Every organizer, every change maker, every visionary is writing science fiction. Envisioning a world in which every person has the full freedom to be their full self is science fiction. Affirming that #BlackLivesMatter when nine Black people are gunned down in one of the oldest Black sacred spaces in the country is science fiction. As any organizer will tell you, vision is essential to social change. It’s the end that every protest held, every call made, every sign flown is pointing towards . It’s the hope for dreaming the impossible into existence.

As we struggle to realize the vision that Black lives matter, we have had to swallow yet another bitter truth. Amid the everyday terror of anti-Black violence in the United States, some Black lives matter more than others. We called out for Michael Brown, but could not remember Tanisha Anderson’s name. We set Baltimore ablaze for Freddie Gray, but forgot to light a candle for Rekia Boyd. Activists and scholars alike have pointed out the irony of this occlusion given that the #BlackLivesMatter movement was started by Black women, and that Black women’s leadership has defined what it means to defend the dead. Just as this violence has a history, so to does this occlusion. In the long and unbroken state of emergency in the United States, it is impossible to understand the contours of anti-Black violence and Black people’s resistance without reckoning with the history of how Black womanhood has been produced as a category of non-being – of how Black women’s very humanity has been made illegible.

Signs made by the Octavia’s Brood Letterpress for a book release party at the Independent Publishing Resource Center in Portland. Photo by Walidah Imarisha

That work of exclusion and erasure is also science fiction, albeit of a different sort than what Octavia’s Brood is writing. When Imarisha calls all organizing science fiction, she implores us to think about the gap between what is and what could be, and about how organizers strive to prefigure the future society they are working towards in their everyday political lives. I am calling Black women’s “paradox of non-being” science fiction because it is not reflective of Black women’s actual lives and work; it bespeaks a debased society that totally and completely erases Black women’s lives. The truth is, Black women face real and horrific state, structural, and interpersonal violence every single day. And it is also true that Black women are leading the movements to end this violence. They’ve been doing so for generations. To not speak this truth, to not #SayHerName, is science fiction. When we do not speak this truth, when we do not Trust Black Women, we become part of bringing to life this sick and twisted universe; we help write a future that looks far too much like our present and past.

***

“THE REVOLUTION WILL BE INTERSECTIONAL OR IT WON’T BE MY REVOLUTION.” These words united a crowd of New Orleanians on May 21, 2015, a national day of action to highlight state and structural violence that Black women face. Not only does local and mainstream media tend to treat this violence as invisible, but it also consistently ignores Black women’s protests against it. The small photo gallery uploaded to Nola.com after the May 2015 event did not name a single organizer or speaker. It was a sick sort of poetic justice. On a national day to #SayHerName, the local media would not. There was not even a mention of the significance of the location of the action: Miss Penny Proud, a transgender Black youth leader at BreakOUT, had been murdered on that site just three months prior. The press did such a poor job of covering the action that one of the co-organizers, Mwende Katwiwa (aka FreeQuency), had to pen her own story about it.

This is certainly not the first time the media has left us with an effaced portrait of Black women’s resistance. On August 14th 2014, people nationally took to the streets to mourn and protest the murder of Michael Brown. Hundreds of people gathered in New Orleans’ Lafayette Park as part of this National Moment of Silence (NMOS). The local news station WGNO ran a simple image-free story covering only the short, scripted portion of the vigil in which Chanelle Batiste read aloud the names of Black people who had been killed by the police, and called all to raise their hands in the now iconic “Don’t Shoot” pose.

What the news omitted was that there were several Black feminist visionaries in front row of that protest crowd. Among them were Mwende Katwiwa and Desiree Evans, both members of Wildseeds: The New Orleans Octavia Butler Emergent Strategy Collective and staff of Women With A Vision (WWAV), a quarter-century old Black women’s health and social justice collective. They completely failed to mention that when the August 14th 2014 vigil crowd began to disperse, Katwiwa asked those next to her, “Really? Is that it?” Then she pushed to the front and called: “EXCUSE ME! Is that all? I know too many busy people here who could be somewhere else but chose to be here. For Mike and others. There is too much collective energy here to waste. If we took to the streets, would you join us?” They did. And people joined. The vigil-turned-march grew to 400-strong before occupying the French Quarter police station – grievances were hurled by a community already well-organized against the everyday racism and terror of its local police force. It took The New Orleans Advocate more than a month to upload a small photo gallery of the action. As with the #SayHerName action, the real coverage of this vigil-turned-march had to be penned by Mwende Katwiwa herself.

National Moment of Silence march on August 14, 2014 in New Orleans. PIctured left to right are Anita Dee, Samai Lalani, and Mwende Katwiwa. Photo by @Small_Affair

There are so many stories like this. For instance, we could go back a few years prior to March 29th 2012. WWAV, under the leadership of Executive Director Deon Haywood had just secured a massive victory. With a carefully selected team of civil rights attorneys, WWAV brought a federal suit against the state of Louisiana for criminalizing Black cisgender and transgender women working in the city’s underground economies. WWAV leadership and strategy created a climate in which a federal judge could, and did, rule that a Louisiana statute for prosecuting sex work as a “crime against nature” was unconstitutional, thereby securing the removal of more than 800 Black women from the Louisiana sex offender registry.

However, the media coverage the next day featured a large picture of the judge, celebrating his courage to rule in the case. WWAV was not mentioned in the article; they had been written out of the story of their own win. Deon Haywood had to write the story of this monumental victory by and for Black women. Resisting media portraits that exceptionalized the “crime against nature” statute as an arcane relic of old South justice, Haywood connected the law and its enforcement to the broader climate of injustice Black women moved through daily in the post-Katrina neoliberal deluge. She claimed WWAV’s victory for everyone who had ever been criminalized and named it as the continuation of the long Black Freedom Struggle. When WWAV’s offices were firebombed and destroyed by unknown arsonists just two months later, Haywood again explained how the attack (and the government’s refusal to investigate) should be interpreted: Fire has long been used as a tool of terror in the South, but it can also be a powerful force for rebirth.

***

The history written by New Orleans organizers like Haywood and Katwiwa refuses to script their work as reactionary, episodic, or somehow secondarily reactive to the oppressions they resist. Nonetheless, no matter how contextual, no matter how historically informed, no matter how deep its roots, Black women’s work is too often treated as though it is an eruption or a reaction, not the continuation of a centuries-long legacy.

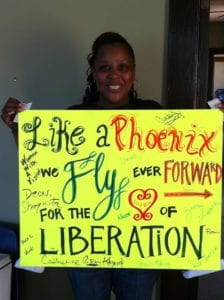

Deon Haywood speaking at a July 13, 2013 Solidarity Rally in New Orleans organized in the wake of George Zimmerman acquittal in the murder of Trayvon Martin. Photo by Sasha Matthews.

The denial of coevalness is one of the oldest colonialist tricks for constructing the “Other” as spatially and temporally different from themself. We might recognize this denial in its more overt manifestations: the descriptions of peopled lands as “empty” or as “blank canvasses;” the minimization of indigenous social and cultural work as “primitive” or “backwards.” However, the scripting of Black women’s resistance as always already reactive is a no less powerful way of naturalizing the time and space of white heteropatriarchy.

To be clear: The strategies, forms, and histories of Black women’s resistance were not created by the oppressive forces with which their work has engaged. Black women created these strategies, forms of resistance, and histories. This work is Octavia Butler’s science fiction. It is Imarisha’s, and Katwiwa’s, and Haywood’s visionary organizing in which God is Change. It is the creation of a world in which Black women write their own stories and their own futures.

To say, think, or write otherwise is no less sci-fi. Ignoring Black women’s work, writing their stories for or without them, can only bring to life a sick and twisted universe in which Black womanhood continues to be produced as a category of non-being – in which we still do not #SayHerName.

***

“The only lasting truth Is Change. God Is Change.”

When we speak the truth of Black women’s lives and work, we become part of changing the universe into ones in which ALL Black lives matter. We also learn a very different way of analyzing our current social order. Human life is deeply and radically connective – in the clutch of an arresting officer’s hand, in the cut of a judge’s tongue, in the grimace of a store clerk; and also in the scarce resources nonetheless shared within each community, in the cascades of laughter that fill the darkest of institutions. This relationality gives everyday Black feminist resistance a vital elasticity. It’s possible to “hunker down” in times of crisis and gather loved ones close; just as it is possible to stretch out and re-form the severed threads of community and thus unravel those of the American empire. In each case, the strategy is the same: Counter social death with a defiance of living. Organize into a world in which it is possible to realize these collective visions together.

We all live history every day. But is that history writing us? Or are we writing it? Octavia Butler asks us to recognize Black women’s writing and organizing as powerful, sacred work – as a collective force that spins the present and future into existence. When we #SayHerName, we are participating in the visionary fiction demanded and crafted by Black women. When we affirm #NotInOurNames, we are participating in the visionary fiction demanded and crafted by Black women. This participation touches us. It changes us. And through the leadership of Black Women, it changes the universe.

“Why is the universe? To shape God. Why is God? To shape the universe.”

Zina Mitchell photographed at the offices of WWAV on May 29, 2012, days after the arson attack. Photo by Laura McTighe

***

Previous articles in Laura McTighe‘s series on race and religion are:

Making Time: Religion & Black Prison Organizing, with Hakim ‘Ali

Haunted Passages: On Carrying the Past and Envisioning Justice

To Take Place and Have a Place: On Religion, White Supremacy & the People’s Movement in Ferguson

***

Laura McTighe is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Religion at Columbia University. Through her dissertation project, “Born In Flames,” she is working with leading Black feminist organizations in Louisiana to explore how reckoning with the richness of southern Black women’s intellectual and organizing traditions will help us to understand (and do) American religious history differently. Laura comes to her doctoral studies through more than seventeen years of direct work to challenge the punitive climate of criminalization in the United States and support communities’ everyday practices of transformation. Currently, she serves on the boards of Women With A Vision, Inc. in New Orleans, Men & Women In Prison Ministries in Chicago and Reconstruction Inc. in Philadelphia. Laura’s writings have been published in Beyond Walls and Cages: Bridging Immigrant Justice and Anti-Prison Organizing in the United States (2012), the International Journal for Law and Psychiatry (2011), Islam and AIDS: Between Scorn, Pity and Justice (2009), and a variety of community publications.