“His last gesture was that he pointed to me that he had been shot in the back,” Aijaz recalls. “We barely managed to give him a spoonful of water and dragged him into a car. He took his last breath before we reached the hospital.”

By Saba Imtiaz

The Akram family’s house looks like any other in Nawabshah, a city in Pakistan’s Sindh province. Its exterior is made of brick and the lane is cramped because homeowners have expanded their properties, building gates and steps onto the road.

Nawabshah is most widely known as the hometown of Pakistan’s president, Asif Ali Zardari. But over the past few years, it has become known for something else: targeted attacks on families like the Akrams.

On February 29, 2012, 78-year-old Mohammad Akram was killed outside his house in this cramped lane.

Akram had been in the city for five months to spend time with his son and daughter. He had a flight booked for March 12 to Australia, where he had lived since 2005, and he had begun shopping for the trip.

On the day Akram died, his grandson Muneeb Ahmad had been driving him around the city. When he pulled up outside the house, Akram told him to park the motorcycle in a shaded area. As Akram walked towards the gate, gunshots sounded through the lane. Aijaz Ahmad, Akram’s son, ran out to find his bloodied father and his wounded nephew.

“His last gesture was that he pointed to me that he had been shot in the back,” Aijaz recalls. “We barely managed to give him a spoonful of water and dragged him into a car. He took his last breath before we reached the hospital.”

Across Nawabshah, another house has been in mourning since the evening of July 11, 2011. Malik Mabroor Ahmad and his brother were going to their office, where clients were waiting outside to see them. His brother went into the office, and heard the sound of gunfire. Mabroor had reached for his gun, but he wasn’t quick enough firing back.

One of his sisters called his home and told the family that their brother had been injured. His wife, Umtus Saboor, began to pray. “I was knelt in prayer, and then I heard that he was dead,” she said. “He used to hate spots on his clothes,” says his sister Rashida Bushra Malik, recalling her brother’s penchant for wearing white from head to toe. “His clothes were covered with blood.”

“When Mabroor was in the seventh or eighth grade, a Hindu spiritual guide had told him that he would not have a natural death,” she says. “We used to make fun of him, but when he died, I realized that we never took that saying seriously.”

Malik Mabroor Ahmad and Mohammad Akram lived separate lives. Mabroor was a well-known lawyer, and lived in a large house in a neighborhood named after his late father, Malik Mubarak Ahmad. Mohammad Akram had recently immigrated to Australia, was taking care of a shop in Nawabshah run by a family member and hoped that his son and daughter-in-law could join him in Sydney one day.

The two families are bound together by one basic fact, and one that led to the houses receiving the bloodied bodies of their loved ones. Malik Mabroor Ahmad and Mohammad Akram were Ahmadis, whose violent deaths are part of a series of attacks on Ahmadi Muslims since the creation of Pakistan. As Ahmadis, they are part of a religious group that is harassed, discriminated against, targeted and killed, all because their faith is considered a form of heresy by extremist groups that have made it their mission to eradicate them.

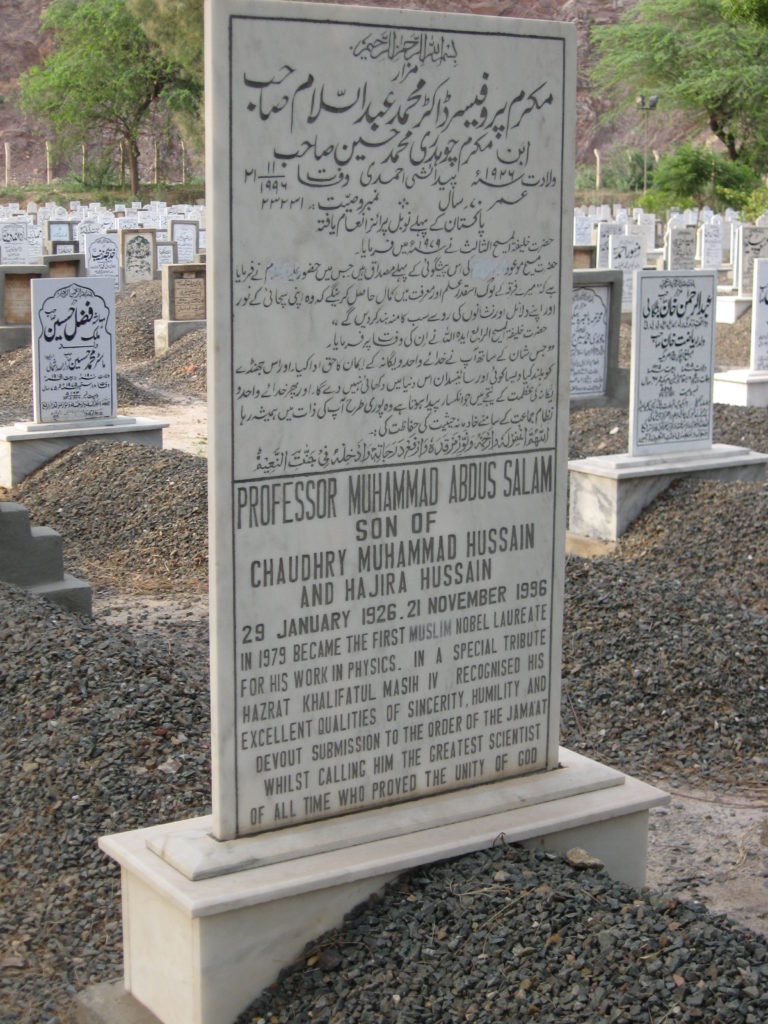

Headstone of Dr Abdus Salam, theoretical physicist and Pakistans first Nobel Laureate in Physics. Dr Salam was a member of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community.

The way we were

It wasn’t always like this in Nawabshah, or in Pakistan, for that matter.

The Ahmadiyya community was once among the most influential in the country. Its ranks included Pakistan’s only Nobel Laureate, Dr Abdus Salam, and its first foreign minister, Sir Chaudhry Zafrullah Khan, along with noted military officers, bureaucrats and doctors. The Ahmadi community is headquartered in Rabwah in Punjab, a picturesque town whose educational institutions were among the best in the district.

Several Ahmadi families migrated from Punjab to other parts of the country, including Malik Mabroor Ahmad’s mother, Mubaraka Tayyaba, and her husband Malik Mubarak Ahmad. Mubaraka Tayyaba is 82 and bore eleven children, all of whom were brought up and educated in Nawabshah. She has partial hearing loss, and her family walks on eggshells around her, trying to shield her from bad news on account of her age and health. In her native Punjabi, she recounted her life and how she came to live in the city. The couple was originally living in Lala Musa in Pakistan’s Punjab province, but after incurring financial losses in their business, they moved to Nawabshah and built a life for themselves. Malik Mubarak Ahmad became an influential figure in the area: the kind of influence that elders in a small city have because they are known for being outstanding citizens, for their land holdings and wealth, and for their wise counsel. Malik Mubarak Ahmad—known as ‘Malik chacha (uncle)’—would endorse candidates for the elections and whoever he backed eventually won. He donated land to the Ahmadiyya community to build a mosque. Contributing money and land to build a mosque is considered an act of charity for Muslims in Pakistan.

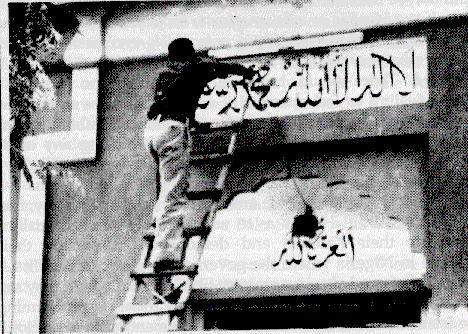

In the 1980s, Malik Mubarak Ahmad found himself being hounded by the police for his donation. In 1974, the government of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had declared Ahmadis non-Muslims in order to appease critics from right-wing religious groups. Ten years later, the country’s military ruler General Zia-ul-Haq passed an ordinance that made it a crime for Ahmadis to identify themselves as Muslims. According to the law, it was made illegal for Ahmadis to use minarets in their mosques, to offer the call to prayer or even to call their mosques, mosques. They are now obliquely referred to as ‘worship places’. Ahmadis who had grown up calling themselves Muslims were no longer allowed to do so, or refer to their faith as Islam. Almost overnight, Ahmadis had become a ‘minority’. The last population census conducted in Pakistan in 1998 states that 0.2% of the 132 million population is Ahmadi. According to the ordinance, Ahmadis could now face prosecution for doing anything that ‘outrages the religious feelings of Muslims’. These laws, combined with the country’s controversial blasphemy legislation, meant that Ahmadis can face the death penalty or jail time for practicing their faith.

These laws have given official sanction to the decades-old campaign of persecution and have led to systematic murders of Ahmadis throughout the country, often by people inspired by religious sermons. The state makes its citizens reaffirm this legal excommunication. When registering to vote, or applying for a passport or an identity card, Muslims must sign the declaration that “I consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Quadiani [sic] to be an imposter prophet and also consider his followers whether belonging to the Lahori or Quadiani [sic] groups to be non-Muslims.”

Malik Mubarak Ahmad was charged with blasphemy because the building that he had helped construct was called a mosque. Ahmad was initially unable to find a lawyer to represent him, in a city where his influence and opinion had once held weight. He was charged, convicted and then freed on appeal. He vowed then that he would provide his son, Malik Mabroor Ahmad, with whatever he needed to help him become a lawyer.

Mabroor married his cousin at the age of 25 and had five children. Two of his brothers also studied law, but Mabroor rose through the ranks. He was known in the city for pro bono work and routinely ran for the local bar association elections just to give the leading candidate a run for his money. “The rival lawyers would hand out fatwas during the voting,” his sister Rashida Bushra Malik says.

After the death of Malik Mubarak Ahmad, Mabroor and his sister took on the task of caring for the extended family. Rashida looked after the house, while Mabroor built up his legal practice.

His acquaintances included Faryal Talpur, President Asif Ali Zardari’s sister, who Rashida recalls once asked Mabroor, “Why are you people persecuted? Explain this to me, I have no idea.”

It’s a question that has plagued the Ahmadiyya community for decades. The difference between the mainstream Sunni and Ahmadi faiths is that Ahmadis believe that the promised Messiah in the Qur’an arrived in the form of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, India, who was the founder of the Ahmadiyya faith. Another group, the Lahori Ahmadiyya Community, believes that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad has no divine link to the succession of prophets. Sunnis, however, believe that the promised Messiah in the Qur’an has not descended on earth as yet.

In Pakistan, it is commonly believed that Ahmadis consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad to be a prophet, thus invoking the notion that they are blasphemers who have disputed the belief that Muhammad was the last prophet. This perception and idea of “blasphemy” – a criminal offense in Pakistan – has led to the Lahori and Qadian groups being banned from identifying themselves as Muslims. Those driven to persecute Ahmadis believe that they are protected by the Shari’a and a Constitution based on Islamic principles, since blasphemy carries the death sentence in Pakistan. Annual conventions are held in Pakistan to reaffirm this opposition to Ahmadis, often with the support of local politicians.

“When registering to vote, or applying for a passport or an identity card, Muslims must sign the declaration that “I consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Quadiani [sic] to be an imposter prophet and also consider his followers whether belonging to the Lahori or Quadiani [sic] groups to be non-Muslims.”

Mabroor had narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in 2008 and had begun to carry a gun, though his sister and sister-in-law fondly recalled how brave he was, and how he didn’t seem cowed by the threat. Rashida remembered telling her brother that clerics ‘scream a lot in September’ – a reference to clerics making angry speeches and holding rallies, during a time that marks the anniversary of Ahmadi excommunication – so she would send him away to a relative’s home in Punjab.

The family had cause to live in fear. Mabroor’s own best friend was killed in an attack. Since Pakistan’s Constitution was amended in 1984, over 200 Ahmadis have been assassinated. Last year, Saad Farooq, 26, was shot dead in Karachi in an ambush after his own wedding. His father-in-law Chaudhry Nusrat Mehmood died of his injuries a month later. Saad’s own father was shot six times and his brother, Ummad, had to be operated on in Birmingham.An Ahmadi graveyard in Lahore was desecrated last December. Organizations such as the Aalmi Majlis Tahafuzz-e-Khatm-e-Nabuwwat (Group for the Protection of the Finality of the Prophethood) routinely leave flyers at Ahmadi houses or stores owned by members of the community. These include lists of Ahmadi businessmen and their shops, or contain warnings for residents of the neighborhood against buying anything produced by Ahmadis. One flyer proclaims “Killing these people in an open market is jihad and is also an act of virtue.” The group’s campaign has even reached London where the Ahmadiyya community has been headquartered since the 1980s.

Mabroor was often approached to stand for public office, but refused because the Ahmadiyya community does not contest elections, nor do Ahmadis vote. This is based on the grounds that Ahmadis do not agree with their legal excommunication from Islam, and hence will not deny their faith in Islam by voting as ‘non-Muslims’ or running for elections on seats reserved for religious minorities.

The state of Pakistan does almost nothing to protect Ahmadis, who frequently ask that if the government does not think of them as Muslims, can it at least consider them as citizens? Malik Mabroor Ahmad would tell his children and nephews and nieces to always follow the advice of the country’s late founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah: work hard and strive for achievements. One of his nephews is also studying to become a lawyer.

A marked life

The police never found who was responsible for Malik Mabroor Ahmad’s death, or for Mohammad Akram’s. Law enforcement officials have rarely acted against individuals involved in hate crimes against Ahmadis, and are often complicit with religious-political groups trying to deface the community’s mosques. They do not act against the discrimination of Ahmadis either, which is prevalent at workplaces, schools and colleges.

Perhaps on account of their elevated social standing, the women in Malik Mabroor Ahmad’s family have been spared the kind of harassment that has dogged other Ahmadis and led to their deaths or seeking asylum abroad. “We are Punjabis, but we are like Sindhis,” Rashida laughs, referring to Sindhi customs of women staying at home. “We do not need to go out to buy anything, even fabric for clothes. Our brothers and nephews do that for us.”

But Mohammad Akram’s middle class family has to step outside the house every day and face the consequences of the decades-long campaign against the community. Unlike Malik Mabroor Ahmad, they have no political influence or arms licenses. They go to their jobs every day, and pray that each member comes home alive.

Aijaz Ahmad is frequently taunted on the street with cries of “Oi Qadiani! We know who you are.” In order to spare his child from being targeted, Aijaz Ahmad has stopped taking him to school. His sister, Sajida Rafiq, had a government official angrily toss aside her son’s passport documentation. A local bakery refuses to serve Ahmad’s family, telling him that, “It is obvious. There isn’t anything for you here.”

Aijaz Ahmad’s wife, who works as a teacher at a government-run school, laughs with a tinge of bitterness. She recounts how a co-worker didn’t give her a traditional gift of prayer mats and spring water after she came back from religious pilgrimage, but gave them to every other teacher at the school.

Malik Mabroor Ahmad’s funeral was well attended, and many turned up to tell stories of how he had helped fight their cases in court without charging any money. When his brother got married, he invited “half of Nawabshah” to the wedding.

But Aijaz Ahmad and his wife are left off the list of invitees to religious meetings in the neighborhood. “Our prayers are slightly different, but we believe in the same thing,” his wife says. The family recalls that there was a time when there wasn’t this much hostility towards Ahmadis but something has changed in the past few years.

“The shopkeepers recognize our burqas,” adds his wife. The burqas worn by Ahmadi families are usually styled as a coat and show more of the face than those worn by women of other religious sects. “And so they don’t serve us.” Ahmadi men wear a distinctive wool cap at religious events, but not as part of their daily wardrobe.

At risk

Mohammad Akram’s children say that a relative told them she was warned of an attack on their father, but never revealed who told her. They would often tell their father to be more cautious. Akram donated money to the Ahmadiyya community and wanted to develop a space for it in his neighborhood in Nawabshah, a city where he spent over forty years of his life before he immigrated with his wife to Australia. The couple was free there: they were able to walk to their children’s homes (five of Aijaz’s siblings live in the country). But Pakistan was always on their mind, even though as Ahmadis, their lives were always at risk.

Purging Ahmadis from the mainstream Islamic faith has been a triumph for the right-wing in Pakistan. The campaign began just a few years after the creation of Pakistan. In 1953, anti-Ahmadi riots broke out in Punjab, stemming from demands by right-wing groups to declare Ahmadis non-Muslims and remove the influential foreign minister, Sir Chaudhry Zafrullah, Khan and other Ahmadi officials from the government. The riots were preceded by attacks on Ahmadi mosques and officers, a campaign of hate speech against Ahmadiyya community leaders and the foreign minister, and calls for Ahmadis to be killed.

A judicial commission that investigated the protests, and the Majlis-e-Ahrar group that led them, found that the riots were well organized, supported by sections of the press, religious leaders and politicians. The position that Ahmadis held in society and politics rankled the Ahrar, as did their own lack of political influence since the Ahrar had opposed the creation of Pakistan in the 1940s. Using religion and the politics of blasphemy became a convenient way for the Ahrar to create a support base in Pakistan and declare that Ahmadis had no space in an Islamic state. This has set a pattern that is now cemented in Pakistan, particularly where allegations of blasphemy are concerned.

While many blasphemy cases stem from actual opposition to a religious sect, religion is often used as a cover to bring blasphemy cases motivated by business rivalries or disputes over land. It is a convenient way to ensure criminal charges are brought against a person: Someone merely needs to say they witnessed an act of blasphemy, amass a crowd, compel the police to arrest the person, and accusers never have to repeat the allegations in court because doing so would constitute an act of blasphemy. In some cases, people accused of blasphemy have been lynched by crowds whipped up by the hysterical allegations of accusers. In Daur, near Nawabshah, an Ahmadi landowning family was recently forced to take the support of its larger clan – who is not Ahmadi — to defend itself against allegations that it had defiled the Qur’an after the family had evicted people from their property. Many Ahmadi families have been forced to sell valuable land and leave the country. Business owners in cities keep a low profile and avoid expanding their operations in order to deter rivals who would use religion to attack them, and to avoid extortionists and kidnappers who would have twice the reason to target rich Ahmadis.

Slowly, and very publicly, Ahmadis have been shoved out of the public space, with no representatives or activists willing to openly call for changes to the constitution to reverse the campaign of discrimination.

Pakistani police erasing the name of the holy prophet Muhammad (saw) from the Kalima of a Ahmadiyya Mosque in Faislabad (at “Sir Shamsheer Road”), Pakistan. Markazan-e-Tasaweer via Wikicommons.

The judicial commission that investigated the 1953 riots against Ahmadis also documented violence against Shia Muslims and conflicts among Islamic sects, pointing to a larger and more worrying issue in Pakistan: that religious intolerance would one day devour the country. A note by a government official cited in the report predicted that “What is happening now, seems almost a writing on the wall and God help us if we do not stop these ignorant people from cutting each other’s throat and thus bringing comfort and cheer to our enemies.”

Far from stopping people from cutting each other’s throats, the government set a precedent by declaring Ahmadis non-Muslims. Anti-Shia groups – led by the Deobandi group, the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan – have demanded that Shias be excommunicated from faith the same way the Ahmadis were. Ironically, several Shia groups had backed the right-wing movement against Ahmadis. But protests against Shias began in the early 1950s as well, with armed attacks recorded in Punjab in the 1950s and in Sindh in 1963. Today, attacks on Shias in Pakistan have grown to an extent that has prompted activists to call it a full-fledged genocide, given the scale at which prominent Shias have been assassinated and their processions bombed.

Just as anti-Shia groups chant slogans calling for their death, calls to kill Ahmadis still echo at rallies by right-wing groups and in the press. In September 2008, prominent televangelist Aamir Liaquat Hussain announced on an episode of his highly popular TV show that Ahmadis were legitimate targets to be killed. Two days later, Ahmadi leader Seth Mohammad Yusuf was shot dead in Nawabshah. A junior cleric in a neighboring district reportedly confessed to the murder. A relative, who declined to be named for this article, said that the intelligence agencies whisked the cleric away and they have no idea whether he was prosecuted. Aamir Liaquat Hussain is still employed and continues to host a religious TV show.

In 2010, 94 Ahmadis were killed in a coordinated terrorist attack at two community mosques in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city, as men had gathered for the Friday prayer congregation. Militants besieged the two mosques and fired at Ahmadi worshippers. Visuals of the attackers scaling the walls were broadcast live on Pakistani television channels, as reporters struggled to find the politically and legally correct terms to refer to the mosques and community. Three days later, militants attacked a hospital in Lahore where many of those injured – including a captured attacker – were recovering. No one has been convicted, even though some of the attackers were handed over to the police after the siege.

There is no one to question what happened to the attackers, or to call on the government to act against those openly calling for Ahmadis to be killed. Since 2010, violence against Ahmadis has expanded across the country. It was once considered to be largely restricted to Punjab, the scene of the violent protests in the 1950s, and Karachi was believed to be relatively safe for Ahmadis. But over the past few years, the growth of extremist and banned groups in the Sindh province has led to similar campaigns against Ahmadis. At least nine Ahmadis were killed in Karachi in 2012 in targeted attacks, a marked increase from recent years. According to annual reports produced by the Ahmadiyya community, two Ahmadis – Hafeez Ahmed Shakir and Dr Najmul Hasan – were killed in Karachi in 2010 and one was injured in an attack in the city in 2011. The spike in killings prompted the Ahmadiyya community’s spokesperson to write to government officials, calling on them to “take action and fulfill your duty to protect the life and property of all citizens without discrimination.” But for Ahmadis to be ‘protected’ by a state that has all but put out a death warrant on them and institutionalized discrimination, is a dream they have long abandoned. For now, they continue to pray.

—

Saba Imtiaz is a freelance journalist in Karachi, Pakistan. She reports on politics, culture, human rights and religion for local and foreign publications and is currently working on a book about the conflict in Karachi. Her work is available on her website, http://sabaimtiaz.com and she can be contacted at saba.imtiaz@gmail.com.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.