Part 2

Childhood and Exile: Rebel Politics and the Politics of Hunger. This post is the second in a series comparing the epic lives of Sundiata, medieval Malian ruler, and Iyad ag-Ghali, a power player and leader in Malian rebel movements for nearly forty years. You can read part 1 here.

(Portions of this article have been updated for accuracy.)

by Joe McKnight

“A short while after this interview between [King] Nare Maghan and his son the king died. [The son,] Sundiata was no more than seven years old.” – Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali

The exact date of Iyad’s birth is unknown, but it was sometime in the mid 1950s in the town of Abeibara, north of Kidal. Iyad was born into the Iriayaken tribe of the elite Ifoghas branch of the Malian Tuareg north, a distinction that afforded a measure of privilege, given their historical position of nobility within the broader Tuareg tribe and clan system. The Ifoghas were even identified as religious elites, tracing their lineage to that of the Prophet. His father had served in the French colonial army and later, as an advisor to the Tuareg elites of Kidal. The family’s privileged position—particularly Iyad’s father’s service to the French army, may have contributed to its future hardships. Iyad’s father was killed by rebels in late 1963. According to one prominent scholar of the region who spoke on background, Ghali ag Babakar had been shot in the head by a rebel commander who’d mistaken him for another elite, and widely hated, soldier. Iyad was probably around seven years old.

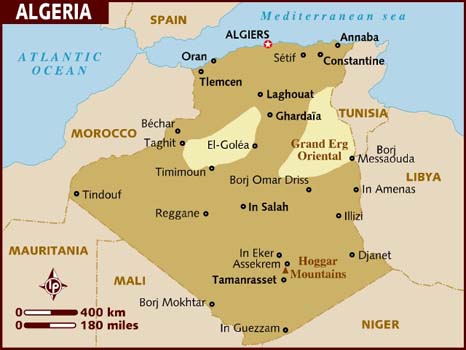

The political significance—the “meaning”—of this first uprising would continue to be debated and shaped for decades to come. One significant result of the conflict and the brutal reprisals from the Malian army was an initial wave of Tuareg emigration to other parts of the Sahel and Sahara region—to Libya and Algeria, in particular. Yet this emigration, which would also grow and continue, was intensified by environmental catastrophe. In 1969—Iyad would have been around fifteen—drought consumed West Africa, and didn’t let up for six years (many scientists consider the subsequent and current droughts in the Sahel part of the same cycle). Hundreds of thousands starved; millions became refugees; almost all livestock were decimated. International aid did make its way toward Mali, but was accompanied by controversy, suspicion and corruption, especially in Taureg northern Mali. To think that the drought wasn’t a formative experience for a young Iyad would trivialize the politics of hunger. Anthropologist Barbara Worley first visited Algeria in 1974 and encountered Malian refugees fleeing the drought, having been denied aid by their own government. As she described it to me: “They felt it was a deliberate attempt to destroy their people. They described vivid memories of government oppression and the Malian army’s brutal retaliations against innocent civilians following the 1960s rebellion.”

Thomas Miles, a scholar of politics and history in the Western Sahel, agrees with Worley, and sharpens her point. In his estimation, the drought had an even more drastic effect on northern Mali than the upheaval of the 1960s rebellion. He says the environmental catastrophe of the droughts in the 1970s and 1980s, “destroyed a way of life,” and fueled an already-existing sense of isolation and anger on the part of Tuareg northern Malians. Miles told me, “from the point of view of the Tuareg, it’s easy to see the early 1970s as a continuation of a planned destruction of their people, whether or not this is true…and it’s harder to fight back against a drought [than against the Malian army].” The legacies of French colonialism, the violence and tenuousness of the new state, combined with the environmental disasters of Mali’s early years as an independent state, were starting to harden into politics in ways that continue to haunt Mali and the Sahel region today.

The crisis of the 1970s—famine, and the repressive martial law imposed by the state on the rebellious north—also pushed the young, now fatherless Iyad into exile, along with thousands of other starving Tuareg. As distinct from most of those others, though, Iyad himself would go on to play a remarkable role in Mali’s future.

“[Sundiata’s mother] and her children…fled from Mali. Their feet ploughed up the dust of roads…Doors were shut against them and kings chased them from their courts. But all that was part of the great destiny of Sundiata.” –Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali

So when did Iyad go into exile, and what does a young man—a boy, still, almost—raised to view himself as noble, a warrior, a leader—do when forced into exile? As early as 1972, according to Baz Lecocq[1], Iyad was part of a wave of desperate Tuareg who made their way north to Libya (many others instead went south to Mali’s bigger cities or to the other urban centers of West Africa). There’s little in the written record to illuminate Iyad’s years of exile but Lecocq observes of his longtime informants that the young Tuareg exiles immediately saw themselves as preparing for a future role in leadership, liberation and armed conflict in their homeland: they saw themselves as a vanguard, not just in military terms but intellectually. Lecocq identifies those exiles as ishumar (a word derived from the French chômage, or “unemployed,” and meaning roughly, “popular intellectuals”), and Iyad was one of them. (Check out a photo of Iyad in Libya in 1972 with one of Lecocq’s informants—we couldn’t get permission to reprint it, but it’s well worth a look at the young Iyad in bell bottoms—just scroll down a few pages). The ishumar set about rethinking the idea of a Tuareg nation, partially with an eye to loosening the old social hierarchies—towards greater equality among the Tuareg themselves. Lecocq describes their experience in the 1960s and 1970s:

[Their] reflections developed through the experiences of international travel, smuggling and (un)employment in various industrial sectors previously unknown in Tuareg society. Their reflections turned largely around the modernization of Tuareg society and the need for political independence through revolutionary action…developed largely through exposure to…revolutionary discourse in Algeria and Libya, which they compared to and measured against their personal experiences. (“Unemployed Intellectuals,” p. 93)

By 1980, Colonel Gaddafi offered displaced Tuareg in Libya an organization of their own (the whimsically named Popular Front for the Liberation of the Greater Arab Central Sahara, or FPLSAC), and military training camps, which Iyad attended. Lecocq told me via email about Iyad’s journey after Libyan training camps were closed in 1981. He wrote, “Iyad and about 250 other volunteers were shipped to Lebanon via Syria, where they joined the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, not out of ideological anti-Zionist or religious motives, but to gain combat experience for their own cause.” After Israel forced the Palestinians from Lebanon in 1982, many of the Tuareg fighters apparently returned to Libya, where there was once again a demand for supplemental fighters. In Lecocq’s observation, “many…later joined volunteer units or the regular Libyan army and fought in [Libyan] campaigns in Chad between ’83 and 85-86.” It’s possible Iyad was fighting among them, but nobody seems to know for sure the exact length and nature of his involvement with the Libyan army.

Those who know the region and its history best at least seem to agree that by the early to mid-1980s, Iyad was somewhere close to his northern Malian home—maybe in Libya or Chad, or maybe in southern Algeria. The English anthropologist Jeremy Keenan has spent decades working in northern Mali and Algeria and is particularly (some, including Lebovich, would say obsessively, polemically) expert on the role of Algeria’s state intelligence service (DRS) in regional politics. Keenan confirms that verifiable details of Iyad in this period are scarce, but told me that one of his longtime Algerian informants insists Iyad had worked in Tamanrasset, a southern Algerian city dominated by Algerian Tuaregs, in the 1980s. Keenan’s view is that Iyad was probably not just punching the clock. “If [Iyad] was working in Tamanrasset,” he told me, “he would’ve been checked out by the DRS…they would certainly have had his number.”

Keenan is not alone in his assessment of either the reach, influence or danger of Algeria/DRS, or of Iyad’s connections with them. John Schindler, professor of National Security Affairs at the U.S Naval War College, shares many of them, and advocates that the U.S. carefully reevaluate its relationship with Algeria and the DRS. When queried by email, Schindler simply responded, “IAG (Iyad ag-Ghali) has been in bed with the DRS for many years, nothing new here.” It may be impossible to “prove” the full extent of Iyad’s ties, but his extensive and documented involvement with the governments and other power players of Algeria, Libya and Mali at the very least suggest an incredible knowledge and sophistication about both the macro- and micro-politics of the region. Andrew Young, probably the single most knowledgeable journalist (writing in English, at least) about this part of North Africa, considers Iyad’s strategic understanding unparalleled, and crucial to the role he’s playing in the current conflict in the north.

Joe McKnight is an MA candidate at Union Theological Seminary, concentrating on psychiatry and religion. A graduate of the Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, he is working to integrate his writing on religion with his interest in foreign affairs in Africa as well as exploration of his Southern heritage.

Editing and additional research by Nora Connor.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.

[1] “Unemployed Intellectuals in the Sahara: The Teshumara Nationalist Movement and the Revolutions in Tuareg Society.” International Review of Social History 49 (2004). p 90.