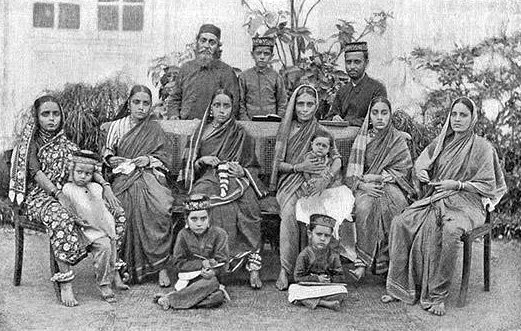

The Poona Haggadah (Poona, 1874). A haggadah published for the Bene Israel community in India features seder illustrations that show Indian dress and customs. Source: U.S. Library of Congress.

by Janaki Challa

Samson Koletkar is an Indian Jew. He is also “the only Indian Jewish stand-up comedian” known in the States, and frequently performs in the Bay Area. “Some of the questions people like to ask me when I say I am Jewish is: Really? Are you really Jewish? Were you born Jewish? Are both your parents Jewish?” Koletkar says in a striking Bombay accent during his well-received performance in the Mahatma Moses comedy tour. “Was I born Jewish? No. I was born a baboon. And as I evolved, I realized I am better than everybody!” he rolls his eyes with a resigned chuckle. Weary sarcasm aside, though, Koletkar highlights the particular grievances of being a minority within a minority—and the eternally debated question: Who is a Jew?

“The story of Jews in India is somewhat of a well-kept secret,” begins the introduction of Jews in India, a book of fifteen academic essays on this little-known element of the Jewish diaspora. The intro continues, “Indian Jews remain peripheral to both Indian and Judaic studies.” They also remain peripheral to the shared culture of the larger Jewish world. Within India itself, Indian Jews have been largely insulated from outside influences throughout India’s complex history. Their small numbers may have helped shield them from persecution, as they were neither very prominent—nor very threatening—as a religious community, though many Jews (such as poet and critic Nissim Ezekiel) have contributed to India’s cultural legacy.

The largest Jewish community in India is the Bene Israel—a Marathi-speaking people found in the enclaves of Bombay. They are descendents of persecuted Jews from Galilee, mostly oil pressers, who were left stranded on Indian shores by a shipwreck around the 2nd century BCE. Marathi speakers call them the Shanawar Tali, or “Saturday oil-pressers,” as they did not work on Saturdays in accordance with Judaic law. For thousands of years, the Bene Israel continued to keep the Sabbath, abided by kosher laws, circumcised their males, and kept the Hebrew language alive in religious practice—though it mainly survived through oral tradition. The Bene Israel’s rituals and rites are very particular—for example, one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Jews in India is in Alibag, where a cleft rock with wheel-marks is believed to have been the rock upon which the Prophet Elijah ascended to heaven on his chariot. Every year, the Bene Israel make this pilgrimage, light candles, and sing songs in Marathi about the Judaism, about the world they had left thousands of years ago.

After the founding of Israel, many Indian Jews emigrated “back” to their religious homeland. By the 1960s, many of them perceived racism in the Israeli state’s lack of official recognition for their community—as if the religious-state authorities didn’t accept them as “really Jewish.” In response to these concerns, the Israeli Rabbinate declared in 1964 that the Bene Israel are “full Jews in every respect,” a public validation of their Jewish authenticity. Today in Israel there are 70,000 Indian Jews, mostly centered around Haifa. This has left barely 5,000 Jews scattered around India.

India’s already small Jewish population has declined over the years since emigration to Israel began. Yet, in an unexpected way, they’ve become perhaps more entwined with global conversations about Jewishness and Jewish identity. Over the past twenty years, it’s become popular with some American Jews to travel to India in order to “educate” the remaining Bene Israel about the halakha, Jewish history, the Talmud, and texts written long after their separation from the global network of the Jewish world. Cradled in their Hindu host-culture, Indian Jews reconcile both their cultural situation and their religious piety—continuing ancient traditions that are not practiced in more text-oriented Judaism. Using green spices instead of dried spices on Passover, for example—or breaking coconuts and offering flowers and fruit upon Elijah’s rock. The oral tradition and isolation from the rest of the Jewish world inform a particular type of piety, which American Jews (apparently led by Hillel and the American Jewish World Service) have recently decided to address and “reconnect” to a perceived mainstream Judaism. There’s a missionary quality to the American Jewish orgs’ enthusiasm for teaching Indian Jews about the contemporary history and current practices of mainstream Judaism, including an emphasis on the written word.

Rabbi Hyim Shafner, an American rabbi based in St. Louis, spent several years in the mid-90s with the Bene Israel, having been appointed by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee to act as a “community rabbi” and resource for the Jews of India (some of whom, like the Bene Israel, have no tradition of rabbis at all). He wrote of his experience working with the Bene Israel:

The Jews of India are not like Western Jews, who need convincing that religion is relevant and meaningful. In India almost everyone is religious in some way, and the Jews of India just want to know how to observe, not why.

After remarking on the mysticism of “the East” (“for peoples…in the East, the spiritual and physical worlds are perceptibly and intimately intertwined”), Rabbi Shafner also chronicles some of the theological challenges generated in the Indian setting, such as the question often posed to him: “Do we Jews believe in reincarnation?” He writes:

The answer I must give them, … was not a complex one drawing on Kabbala or the Talmud, but rather, a clear, ‘no, we Jews do not believe in reincarnation.’ Reincarnation is perhaps the central tenant [sic] of Hinduism, the Bene Israel’s host culture. The Bene Israel work hard to be separate from their polytheistic Hindu neighbors while still living integrated among them. Knowing full well that much of Kabbala, philosophy, and even Midrash does accept the notion of reincarnation, I tried to muster a definitive ‘No!’

Rabbi Shafner—and those American Jews participating in an organized trip to India—are guests in an Indian Jewish setting, though they may assume or represent a kind of “mainstream” Jewish authority or knowledge. When Indian Jews are part of a diaspora, though, such as in the United States or Israel, the question of their connection to the “story of the Jews” comes to the fore in a much different way. What about minorities within the minority, whose lives and histories were so far removed from Europe and the Jewish world for so long, whose experiences were largely untouched by anti-Semitism or religious persecution? How does Jewish identity manifest itself without those connections to the “Jewish story” as most of us commonly understand it—the holocaust, Israel, the Ashkenazic history and cultural influence?

My interviewees in New York, members of an Indian-American Bene Israel community, have some answers to this question. One, who asked to remain anonymous (I’ll call him Ezekiel), is a twenty-four year old Indian-American Jew, born and raised in Brooklyn and part of an Ashkenazi community near Crown Heights. Ezekiel explained it this way: “It doesn’t matter whether it [the Holocaust] was in Europe or anywhere else, it does not matter—the point is that it happened, and we are Jewish brothers. And it was a crime against humanity…all Jewish history is a part of my own history. I am a part of the nation [of Israel] as much as I am Indian.”

Bene Israel Jewish cemetery, Bombay. Photo: By Christophe cagé at fr.wikipedia, from Wikimedia Commons.

But what of the ways in which American Jews, and the broader American public, may perceive—or fail to perceive—Ezekiel’s Jewishness? Does the visibility of his Indian-ness in this American setting interfere? “Obviously, I look Indian, and I am an Indian Jew. But I am also Jewish, and that is cultural too. It doesn’t matter,” Ezekiel told me when I asked about race. “A Jew is a Jew. Of course, there are people who make you feel like you are not ‘really’ Jewish, or ‘Jewish enough.’ But there are always those people in any community. We follow the Torah, go to temple, we follow all the mitzvot [613 Judaic commandments], we keep kosher. It doesn’t matter what others say. I know what I am.”

Romiel Daniel is an Indian-born rabbi, and president of a mostly Ashkenazi synagogue in Queens. When asked about discrimination from other Jews in the US, he had an interesting response: “We want to integrate within mainstream Judaism, not assimilate.” Rabbi Daniel also founded the Indian Jewish Council (IJC)—because, as he said in a 2008 interview with The Jewish Press, “there was nothing in place for [Indian Jews] to celebrate our culture, rituals and traditions.” He emphasizes that Indian Jewish rituals date back over 2000 years (surviving more or less in isolation), and are very different than Sephardic or Ashkenazi rituals. He implores “mainstream Judaism” to learn about these different—but equally important—cultural practices.

There is no binding, formal collective of Indian Jews in New York—though there is the IJC, and a rented synagogue on 12th street that occasionally opens up for worship and lectures. I’ve interviewed and spoken informally with ultra-Orthodox Indian Jews, who are integrated into Sephardic communities. I’ve spoken to a Hasidic Jew of partial Indian (Bene Israel) origin. I’ve talked with people of Indian descent who have recently converted through conservative rabbis, and those who dismiss those converts for not having gone through an Orthodox conversion. Some are Zionists; some are not.

There seems to be an element of elasticity with Indian Jews, in contrast to other diasporic populations such as the Yemenite, Ethiopian or Persian Jews— a seemingly individual integration into Jewish communities of their choice rather than holding on to a history of specific practices, or any tightly clustered collectivity. There are kosher Indian restaurants on Lexington Avenue, such as Shalom Bombay Glatt Kosher Restaurant or Madras Mahal, exclusive internet groups and forums, now mostly transitioned to Facebook groups (generally open only to members of the Bene Israel diaspora), a few cultural organizations. But generally, perhaps due to lack in numbers or resources, it seems this community is more or less bound by word-of-mouth connections, and eager to rejoin the larger Jewish world—at the risk of losing an ancient set of traditions, often dismissed by their co-religionists as “outdated,” though some–like Rabbi Daniel, argue that they are worth preserving in integration with a more mainstream sect.

In many cases, social tensions about identity, race and the like are not explicitly expressed in conversation. Oftentimes, grievances are written about in literature, manifested in art and performance—as with Samson Koletkar’s humor: “Are my parents Jewish? [other Jews often ask]. No, my mother is a Christian, and my father is a Muslim, and they hated each other so much, they decided to make me Jewish!” He shakes his head, and extends the mimicry of such suspicious questioning by directing it at Biblical figures. “[Would you go to Abraham and say] Are you really Jewish? Were you born Jewish? Are both your parents Jewish?” Obviously, the Biblical Abraham wasn’t “born Jewish” and neither were his parents. “So according to that logic, there are no Jews in the world,” he concludes, and throws up his harms, almost muttering an “oy!”.

His point is well taken: the question of identity is complex, and inconclusive. It is at once more complicated than it looks on the surface, and, paradoxically, at times far simpler than it sounds. When Rabbi Daniel’s wife, Noreen, was asked in an interview, “What might surprise our readers about Indian Jews?” she responded aptly, and anecdotally: “The first surprise would be that there are Indian Jews.”

Janaki Challa is a writer and graduate student in the NYU Religious Studies Program. She is a research fellow at the Howard & Edna Hong Kierkegaard Library. Janaki is currently working on a book about Jewish minorities, including the Bene Israel. She can be contacted at jc4844@nyu.edu.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.