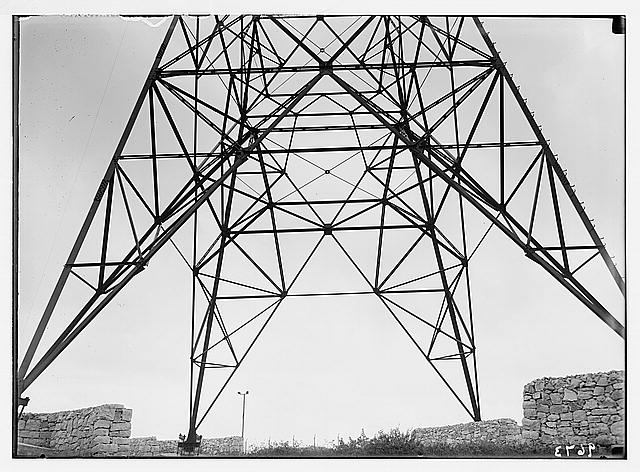

Radio masts and station, Ramallah, approximately 1935. (Photo: American Colony (Jerusalem), Library of Congress collections.)

A review of Arab Media: Globalization and Emerging Media Industries. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2011. 256 pp.

by Narges Bajoghli

Arab Media: Globalization and Emerging Media Industries, edited by Noha Mellor, Muhammad Ayish, Nabil Dajani, and Khalil Rinnawi, provides a succinct overview of many different facets of Arab media. The editors include a breadth of information on books, publishing, radio, television, cinema, and the Internet across Arab countries. What is compelling about this book is its useful series of short chapters that provide a brief and overarching introduction to the media landscapes in Arab countries, and for that reason, it can be used in classrooms. In this way, the editors provide an almost encyclopedic overview of Arab media set against the socio-political changes in Arab countries from the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Despite the work’s accomplishments, three missed opportunities stand out in particular: an analysis of specifically religious and Islamic media; engagement with a wider array of sources, including primary sources; and inclusion of ethnographic work to complicate their reliance on media structures alone. The authors do not seriously engage with the plethora of religious media in the Arab world, thus ignoring an important arena of media production and consumption and leaving gaping holes in the book’s coverage. Virtually no primary sources are cited and little attention is paid to anything beyond the macro-structures of media industries in the Arab world. The authors draw mainly upon secondary data (surveys, economic statistics, think tank and policy papers, and research from other scholars), including no ethnographic material on how producers and consumers of media negotiate the various financial and political constraints on the ground in creative ways. In general, this book reads more as a policy paper, which makes specific recommendations for the “improvement” of Arab media in a quest for democratization, rather than a complex academic study. For example, Nabil Dajani writes in the chapter on Arabic books: “Another serious challenge to printing and publishing is the mushrooming of television channels that mainly distract the viewers from published work and have addicted Arab viewers to kitsch and low cultural products. Improving the quality of television programs can perhaps stretch the viewers’ interest to seek more information in published works” (43). Dajani provides nothing to back up his claims. In what ways do television channels, themselves, addict Arab viewers? Who are the agents involved in this process, if we are to take it seriously? And what makes the programs he refers to “kitsch and low cultural products”?

The authors of this book should have instead looked to the work of Lila Abu-Lughod in Dramas of Nationhood, who provides in-depth research with viewers of Arabic language television (in this work, the focus is on Egypt, popular media and notions of the Egyptian nation). By not engaging with consumers, distributors, and producers of various forms of Arab media, the authors have created a highly simplistic account of media in the Arab world. Muhammad Ayish states in his Arab Media chapter on television: “television in the Arab world is more likely to remain captive to patriarchal and authoritarian political traditions than define how populations relate to society and the state” (102). In this regard, research by the likes of Lila Abu-Lughod, Lisa Wedeen (Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric and Symbols in Contemporary Syria), and Julie Peteet (“The Writing on the Walls: The Graffiti of the Intifada”), for example, provide a stark contrast to this book. These authors are exemplary in avoiding simplistic frameworks to analyze “state-controlled” or “privately owned” media versus “illegal” or “democratic” media. Through providing on-the-ground examples of the ways in which people engage with and produce media, these authors move us towards an appreciation of the mutually constitutive relationship between the forces that ultimately shape social identities. This creates the space to recognize and analyze the social and political agency of individuals in contributing to and creating media of all types.

It is true that mass media have been used (and still are, in some contexts) as a means of social engineering: to foster national development, as Abu Lughod points to in Egypt; to create loyalty to the state, evident in Wedeen’s depiction of Assad’s cult in Syria; or to advance specific ideologies. In this fashion, national media is/was utilized for political and social projects, specifically in postcolonial nations, as Abu-Lughod notes of Egyptian popular media: “the addressee was the citizen, not the consumer. Audiences were to be brought into national and international political consciousness, mobilized, modernized, and culturally uplifted.” Nonetheless, while recognizing the ways states have used media in projects of control or domination, we must complicate our understanding of the hegemony of state-controlled media. The state is a complex set of institutions comprised of different people with various goals and ideologies. We cannot grant “the state” an individual, all-powerful identity; it is not “the state” that censors or creates media, but individuals within state structures who themselves have a complex and multilayered relationship with the state. As Wedeen aptly points out, vis-à-vis Syria, “even members of the regime who are directly responsible for disseminating propaganda and ideology sometimes acknowledge the disparity between the slogans they produce and the political convictions they hold.”

And we must recognize that the overarching term “state-controlled media” can be a misnomer because the state does not have complete control over all media products. Rather, creative, diverse, individuals take part in the production of media. If we ignore the negotiations and struggles that take place within states to produce various programs for “state-controlled” television, we then run the risk of essentializing the state and its powers and we rob citizens of their agency by ignoring or overlooking their specific roles and struggles in the production process. Wedeen points to the ways in which artists and organized opposition created a “thaw” in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Syrian media: “This ‘thaw’…was a response to…the persistent attempts of individual, educated artists, playwrights, film directors, poets, cartoonists, and novelists to produce work offering an alternative to the regime’s self-proclaimed ideals of omnipotence and indispensability.”

It is also imperative to remember that the state cannot control how people interpret what they see. Though a state may wish to control its media, it does not own any conceptual system; hence, it may want to produce power and generate community through its symbols of spectacle and mass media, yet it cannot control the ways in which its public will consume and potentially subvert these symbols. It is precisely through consumption that transgressive actions and responses may develop, leading to a dynamic interplay between the regime’s power and people’s reaction to that power, as Wedeen reminds us. The existence of “illegal media,” such as the Palestinian graffiti that Peteet examines, can create and evidence a contested space and challenge prevailing hierarchy. Palestinians are denied a political and cultural space, and graffiti during the first intifada became visible responses to, and resistance of, an occupying force that blatantly excluded them from any public space. The graffiti challenged hegemony and, Peteet observes, “simultaneously affirmed community and resistance, debated tradition, envisioned competing futures, indexed historical events and processes, and inscribed memory.”

Yet all illegal media is not the same. Like “state-controlled media,” the term “illegal media” begs for additional explication. Resistance and reactions develop within the space of specific assertion and repression, using the tools at hand and operating within the constraints and possibilities that this space allows. As such, each resistance is a (by)product of its environment, specific to its circumstances and not reducible to a generalized notion of “illegal media” as a whole. In order to better understand and analyze illegal media we must understand the particular power and domination at work. In the case of Syria, it calls for an understanding of the myriad ways Assad’s cult induced complicity; in the Palestinian territories it requires an analysis of the multilayered forces of occupation; and in Egypt it calls for a deeper look into the role of developmentalism in nation-building, to say nothing of the myriad forms of media in other Arab states. Examining resistance in a particular context allows us to view illegal media in their complexity and diversity, acknowledging the variety and specificity of transgressive acts within media ecologies.

If we gain a better understanding of resistance when we analyze the particular situation from which it arises, we are likewise prompted to look at the ways in which state-controlled media and illegal media are in a dialectical relationship. In Syria, for example, Wedeen points to the fact that the Assad cult and its attendant media spectacles not only produced power, but they also, paradoxically, invited transgressions. The spectacles and the regime’s iconography delineated the images and vocabulary for not only complying with the regime, but also contesting it. Therefore, the play on words and the symbolism used in cartoons, comedies, and dramas in Syria carefully treaded close to the redlines, while allowing viewers to actually cross these redlines in the privacy of the home through joke-telling. Abu-Lughod looks at the ways in which the pedagogical messages of television serials are not simply transmitted from ‘the state’ to its ‘objects,’ but between two performative subject-groups: an elite who produces media and an audience who critically interprets the media. These subjects, moreover, are not isolated; the audience interacts with the producing elite through a series of encounters depending on their experiences and the alternative discourses available to them.

Peteet, similarly, looks at the ways in which graffiti were polysemic in the Palestinian case. The graffiti addressed two publics, the Palestinian community and the occupier. The graffiti simultaneously communicated messages to the Palestinian public, built community, and registered resistance, while signaling defiance and lawlessness to the Israelis. This illegal graffiti not only provided political commentary and directives to its readers, but it signaled resistance to occupation and “suggested the sense of community and assertiveness of a readership bound by common political experience and language.” In this interplay between resistance and domination meanings are constructed: in the case of Syria, this interface produced a vocabulary not only for complying with Assad’s regime, but also for contesting it; and in the first intifada, the interplay affirmed a sense of community and a common social identity which sought to overthrow hierarchy.

The above examples exemplify the importance of an ethnographic approach when analyzing media. Ethnographic data positions the researcher to look at how people interact with and interpret media, allowing us to move beyond generalizations by looking at real practices. As Wedeen observes, ethnography helps “get at the meaning of symbols, rituals, and practices in a way that avoids a simple functionalist interpretation.”

References:

Abu-Lughod, Lila. Dramas of Nationhood: The Politics of Television in Egypt. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Peteet, Julie. “The Writing on the Walls: The Graffiti of the Intifada.” Cultura Anthropology 11(2), 1996.

Wedeen, Lisa. Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Syria. The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Narges Bajoghli is a PhD candidate in socio-cultural and linguistic Anthropology at New York University as well as a documentary filmmaker in NYU’s Center for Culture and Media. Her research focuses on the production of media and popular culture in Iran. She is the director of the Chemical Victims Oral History Project in Tehran, as well as the co-founder of the 501c3 organization Iranian Alliances Across Borders (IAAB, www.iranianalliances.org). Read Narges’ other work for The Revealer here.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.

Front page image from “Wendell Steavenson’s “Revolution in Cairo: A Graffiti Story,” New Yorker, July 27, 2011.