by Joe McKnight

This should not be my first interview. That’s what I’m thinking during my haircut, a feeble attempt to look more professional. I hear a classmate’s voice in the chair next to me; he asks what I’m doing and I tell him. Really? Yes, really. I hand him the fifth draft of my questions, and after he looks them over, I ask if he has any advice. “Practice deference,” he answers. Good lord, yes! Being from the South, if I’ve been trained to be anything, it’s deferential.

“Do you think I should tuck my shirt in?” I ask my classmate.

“Doesn’t hurt,” he replies.

When I knock on the door, no one answers. Maybe he forgot! Hallelujah! I ring the door-bell; there is rustling. I thought I’d left behind the notion of divine intervention after my first year of seminary, but the hope that it exists comes roaring back. I’m that scared. It will have to be God, James Cone, and me.

He stands in the doorway, grinning. Despite his 73 years, I’m certain his face has changed little since his youth. His once soaring afro, however, has. He is wearing black slacks and house slippers; he wears his button down oxford lightly. Its pattern can only be described as Africa-meets-hounds-tooth, a look befitting Dr. Cone’s legacy. He asks me to sit in a deep-seated chair in his spotless apartment. I do not lean back. Both of our shirts are tucked in. I am sitting alone in this living room with the father of black liberation theology.

This isn’t my first encounter with James Cone. As a student at Union Theological Seminary, I’m often within range of the famed and intimidating theology professor. But I was first introduced to Dr. Cone and his theology on cable news an election cycle ago.

In 2007, after Obama announced his campaign, I watched Sean Hannity interview Reverend Jeremiah Wright. Hannity accused Wright and his church, Trinity United, of employing institutionalized racism and separatism, all while the black man who would be president sat quietly in the pews. Wright was sowing the seeds of white hatred in his black congregation, Hannity charged. Wright went on the offense. He asked Hannity repeatedly, “How many of Cone’s books have you read? ”

Almost a year later, ABC aired this story highlighting selected clips of a few of Jeremiah Wright’s most controversial sermons. The cable news mob arrived and overnight, “black liberation theology” became the most serious threat to American politics. Five days later, his campaign hemorrhaging, Obama flew to Philadelphia to give his “race” speech, “A More Perfect Union.” The campaign survived, but the controversy proved to be one in a long history of attacks on the tradition of many black churches.

My introduction to Cone was not unlike that of many other white Americans previously removed from the world of black liberation theology and its indictment of the success of white America.

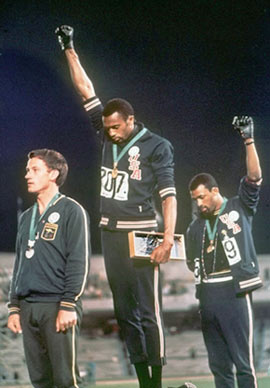

When I was 14 my mom handed me The Autobiography of Malcolm X. My life changed. A white boy from Tennessee, I read as much as I could about the militant element of the African-American freedom struggle of the 1960’s, a struggle necessitated by my people, in my home. With Malcolm at the center, figures such as Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, Angela Davis, Louis Farrakhan, George Jackson, and Fred Hampton pointed to the underbelly of what Malcolm X termed, “the American nightmare.” And yet, Cone, the man responsible for integrating the political identity of Malcolm X with the Christian theology of Martin Luther King Jr., was often absent from the more popularized discussions of the freedom struggle I studied in my late teens. The discovery of a theology that underpinned the Olympic black power salute of John Carlos and Tommie Smith in 1968 was a revelation. Years later, when applying to divinity school, I knew I wanted the perspective of liberation theology woven into my education.

Black liberation theology’s explosive re-entrance onto the national stage in 2008 – during my early twenties – made Cone as compelling as any of the activists or academics I had studied previously. I had grown up in moderate-to-liberal Presbyterian and Methodist traditions, groups that prided themselves on their stances of racial equality and social justice. How could I have heard nary a word about the fiery, prolific writer who illustrated how the Gospel spoke directly to the predicament of poor, marginal African-Americans? Forty years after the publication of Cone’s provocative Black Theology and Black Power, why was the nation’s reaction still so hostile? Just who then is James Cone?

Born in 1938, Cone grew up in the small town of Bearden, Arkansas, in a tight-knit African American community. His childhood was one fraught with the contradictions of racism in the “Christian” South. He writes in The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011), “During my childhood, white supremacy ruled supreme. White people were virtually free to do anything to blacks with impunity. The violent crosses of the Klu Klux Klan were a familiar reality, and white racists preached a dehumanizing gospel in the name of Jesus’ cross every Sunday.”

At sixteen, he left home for the ministry and eleven years later, he graduated with his Ph.D. from Northwestern University. At the time, he was the only African-American with a degree in systematic theology in the United States.

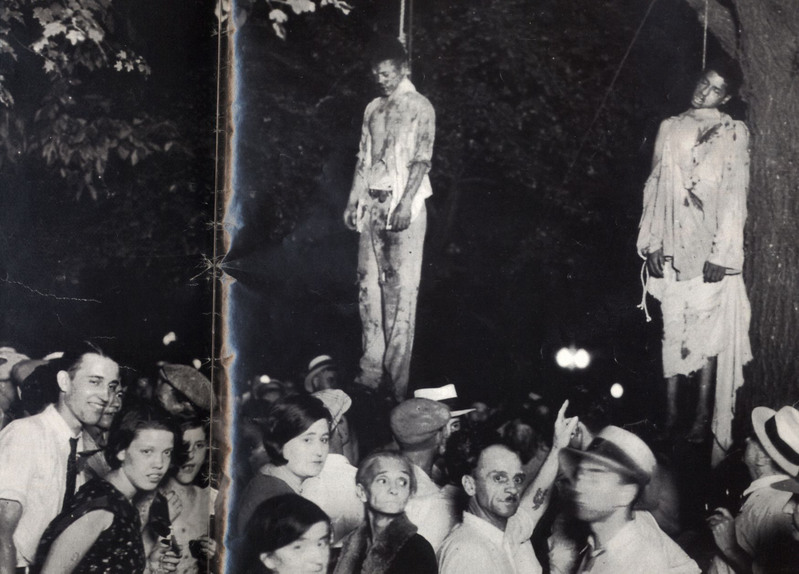

In Cone’s “Introduction to Systematic Theology” class last fall, a rite of passage in the Union curriculum, he described how, during his first three years teaching at Adrian College in Michigan, he burned with rage. In Cone’s judgment, since the Enlightenment and the rise of modernity, the primary theological discussion was belief vs. non-belief. The rise of orthodoxy in the face of biblical skepticism, the response of theological liberalism to the dogma of orthodoxy and neo-orthodoxy’s condemnation of liberalism’s acculturated God: all these ignored the issue of the non-person. Cone clearly saw that, at the very same time the debate over belief raged on, millions of Africans were being shipped across the Atlantic to be sold. While the authority of Scripture was called into question, Jim Crowe reigned supreme. When Reinhold Niebuhr engaged the symbol of the cross with new depth he still failed to draw any parallel to the modern American cross–which bore the deaths of some 5,000 African Americans – the lynching tree.

Cone spent the second half of his young life striving to move higher and higher within academia, as he tells it, to reconcile the Gospel with his own experience and the experience of his people. Instead, he found a Gospel that not only ignored his experience, but effectively denied it. Karl Barth, the founder of neo-orthodoxy–and the subject of Cone’s dissertation–became the “enemy.”

By the summer of 1968, the men through whom Cone had found his voice, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, had both been slain. They had been roughly a decade older than Cone; they were both dead by 40. Civil rights legislation had been passed, yet hundreds of cities across the country were burning. The “fire next time” that James Baldwin had written about in 1963 was burning down Chicago. Cone was on fire too.

Drawing on the centuries-old legacy of liberation within the black church, Cone endeavored to flip the Gospel of white Western Europe and North America on its head. He returned home to Arkansas for the summer possessed. He wrote eight hours a day, except on Sundays; Black Theology and Black Power was completed six weeks later.

“The 1967 riot in Detroit killed 43 people. I was living at the time in Adrian, MI, about 70 miles from Detroit. That was the event that changed my life and made me decide to write the book,” Cone told me via email.

Black Theology and Black Power remains one of the most poignant expressions of the righteous fury that was swelling within the more militant Christian and African American communities in the 1960’s. Almost thirty years later, Dwight Hopkins, professor of theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School, spoke of the impact of Cone’s book, “The publication of Black Theology and Black Power was the first time that liberation for the poorest in society was interpreted to be the central message in the gospel,” Hopkins said at the “Black Theology as Public Theology” conference in 1998.

“In the book, Cone said that churches may need to be concerned with the salvation of individuals, but the black church as a whole is not a Christian church if it does not concentrate on the structural liberation of poor communities,” Hopkins continued.

The year of the book’s publication, 1969, was the same year Cone began teaching at Union Theological Seminary in New York. Only a year later, he published A Black Theology of Liberation which is still regarded as the systematic manifesto of black liberation theology. He’s since published eleven more books, edited numerous anthologies, written hundreds of articles, and lectured on almost every continent. Still at Union, Cone is considered to be a pioneer within his field, the African American community, and an icon of his time. And I’m sitting in his living room.

Regardless of how my perception of Cone and black liberation theology has changed since enrolling at Union, my fear of him remains. The anger of his late twenties, splattered in quotes across the screen, made for sensational headlining. I viewed black liberation theology, with its condemnation of white America, as an existential threat to the God of privilege and neo-liberalism (to which I could only belong). The characterizations, dated and misleading, ignore both historical context and, certainly, any notion that Cone or black liberation can evolve. But they’re still powerful.

By the time of the interview, I had read enough liberation theology and heard enough of Cone’s lectures to understand the gross hyperbole that accompanied the reporting in 2008. My anxiety about interviewing Cone wasn’t necessarily fear or intimidation, but Cone’s critique of privilege; that we will be judged both here and in the great beyond according to the condition of the dispossessed and the marginalized. As Cone said during the interview, “If America were interested in the poor or if the media were interested in the poor, then there would not be nearly 50 million poor people in this society.” To be in conversation with a man whose personal and professional life have been a sometimes complicated, often controversial, but permanent commitment to the struggle for justice necessarily demands a re-evaluation of one’s own priorities.

Towards the end of our interview, I asked Cone about the importance of love in his upbringing and in the world today. He responded, “For all times, first thing people need is love,” his voice cracked, “They need to be loved and they need to love.” At seventy-three, the self proclaimed “angriest theologian in America” was almost in tears at the mere mention of love. It was clear that the word resonated deeply with the man known mostly for his commitment to justice. Perhaps, it was only on the long and treacherous journey towards the “mountaintop,” of which King spoke in the hours before his death, that Cone had glimpsed the paradox of his life and his struggle – that the fight for justice without love negates both. That’s the kind of wisdom beyond any theology or parable, but is arrived at only through the experience of walking along the precipice that Cone and few others have been willing to tread and that I, frankly, am terrified to follow.

Joe McKnight: What did you think of the nation’s reaction to black liberation theology, in the form of Jeremiah Wright, in 2008?

James Cone: Well, you know, it reminded me just how much the media gets it wrong. And it also reminds me just how much the media is really not interested in knowing what black liberation theology is or what Jeremiah Wright really is about or what his church really does for the community in which it serves. And also not really interested in the positive role the church might have played and Wright might have played or black liberation theology might have played in the life of Obama. I don’t think the media or the public was really interested in that.

I think the political discourse and the religious discourse is really not intended, as it comes through the media, to really explain anything in a way that serves the other purposes they have. I felt that about how Wright and Obama were talked and how black liberation theology was used in that context. I felt that there was very little I could do to clarify what black liberation theology really is about, largely because they weren’t interested in it. They were interested in the explosive nature of it rather than the reality to which it pointed.

JM: Has that reaction influenced your work since? You’re up against quite a machine ,the media.

Cone: My writing of black liberation theology has not been primarily for the media. And it’s not been primarily for the masses in the political public, that is, people who are interested in symbols and distortions and simple sound bites. Black liberation theology is not a sound bite. To understand Jeremiah Wright, you can’t do it with a sound bite. I think the media is primarily interested in that – sound bites. They are interested in that for their purposes and not for the purposes that black liberation theology might have in mind or I might have in mind.

JM: Did it affect The Cross and Lynching Tree, which came out last year.

Cone: I’ve been writing The Cross and the Lynching Tree over a long period of time. I was writing it before the Obama and Wright controversy emerged. The book emerged out of my attempt to understand what the gospel of Jesus and his cross might mean for America. Especially for America since they crucified so many marginal black people in its history through lynching, the same way Roman society crucified Jesus and so many marginal and poor people during the time of the empire.

I wanted to suggest that maybe if Americans could see the cross in the light of the lynching tree, they might be able to understand what the cross really meant in the 1st century and what the cross might mean for the people who have put other people on crosses.

JM: Why does the media interpret black liberation theology the way they do?

Cone: The media wants to sell papers, they want to attract viewers to the cable shows, the mainline shows. I don’t think the media is interested in understanding anything deeply about black liberation theology. I didn’t write it for the media – I wrote it for people who were struggling for justice. Black liberation theology is the voice of voiceless people. It’s the voice of the marginal groups, people within the black community and also within America. Black liberation theology was not written for upper class black people. I wanted to provide hope for hopeless people and I wanted to provide faith for a people who had their backs against the wall. Who were not recognized and acknowledged by America. So I wanted to speak for them – that’s what I think the gospel of Jesus Christ is about. It is not about being the most popular theology or the most popular preacher. And that’s why I did not respond to all of the requests that were made from all the cable shows for me to come on TV and explain black liberation theology. I would have done it, if I thought they were really interested in it. But I knew they were not and I knew they would take what I said and do what they did with what Rev. Wright said.

JM: Is that the voice America is still not ready to listen to, the people struggling for justice?

Cone: I think America is ready to listen to the dominant voices, the dominant people. Dominant people in terms of economics, politics, and religion. That’s who has a voice in this society, but you know, society at the time of Jesus was not interested in Jesus, that’s why they crucified him. So it does not surprise me that the American public is not interested in the gospel of Jesus or black liberation theology or any type of liberation theology because that theology speaks for the poor and America is not interested in the poor. If America were interested in the poor or if the media were interested in the poor, then there would not be nearly 50 million poor people in this society.

JM: Despite Jeremiah Wright, where is black liberation theology in Obama’s administration?

Cone: I don’t think it plays any particular positive or negative role. I’m sure if it has any positive role to play, I’m sure President Obama is probably not conscious of it. I think black liberation theology is a prophetic theology, not a theology of the Democractic party or the Republican party or any party in this society. Black liberation theology takes its cue from Moses, Abraham, Isaac, Amos, Jacob, Jesus, Paul. It takes it cue from the biblical message, not from the American political process. So black liberation theology will never be very popular in America. I didn’t write it to be popular, I wrote it to speak the truth about America through the eyes of the Christian gospel and that’s why it will not be good news from the standpoint of America, but it would be good news from the standpoint of the gospel itself.

Hear audio of this response: James Cone on the media and Black Liberation Theology

JM: Will Mormonism have as much of an impact on the 2012 election as black liberation theology did in 2008?

Cone: I don’t know. It’s hard to say. I think Mormonism is certainly not a very popular faith expression among white evangelicals or evangelicals of any sort in this country. Certainly, it’s not popular in the black community because Mormonism just recently corrected its belief that African-Americans were an inferior people. Even then, you won’t find many black people responsive to that, but you will also find many white conservatives not finding Mormonism as an expression of the Christian faith, but more like a cult.

So, its going to have its own controversies, but I think America will be able to accept Mormonism as a part of its own religious diversity, the way it accepted Roman Catholicism, the way it accepts black religion, the way it accepts other religions – Islam, Buddhism. I don’t think Mitt Romney’s Mormonism is going to have a lasting negative effect on the political process in this country. It may have a negative effect this time, but I don’t think it’s going to be permanent.

JM: How is black liberation theology, how are Malcolm and Martin operating today?

Cone: I see Martin always expressing what America could be but is not. I think Malcolm will always be an expression of the nightmare. Of why America is not what it could be. I think most people in the urban ghettos respond to Malcolm’s description of the nightmare in America largely because it’s apart of their experience, that’s what they see. They don’t see easily how they can get out of it. The nightmare is real for the people at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder in urban centers.

But Martin King speaks of hope that the nightmare is not the last word. That people can actually change the nightmare and move toward the dream. I think you need both Martin and Malcolm today, as you did when I first wrote that book [Malcolm and Martin in America: A Dream or a Nightmare (Orbis Books, 1992] or as we’ve seen it in the history of America. Namely, Malcolm expressing the nightmare of the very depth of black suffering created in part by white supremacy.

Martin King expresses the dream–the possibility, the hope–that America is not just for black people, but for people all over the world. America has always been regarded as a white man’s country and yet, at the same time, we know that’s not how America always will be. It will be a country for all of the people of this society and not just for whites.

JM: How can Martin and Malcolm speak beyond the black community?

Cone: I think Martin and Malcolm represent two dimensions within all marginal groups who are struggling for justice in any society. Malcolm represents that nightmare, the loss of hope. He articulates that loss of hope. Any group that’s struggling is in part addressing a nightmare. They are addressing the failure of the society to acknowledge their full humanity. That’s what Malcolm represents.

King represents the hope that these people can actually change their nightmare into a dream, into a new world. I think all people struggle with that. I think there’s a little bit of Malcolm and Martin in the women’s movement. I think a person like Mary Daly in religion expresses what Malcolm expresses. The despair of women trying to achieve justice in this society. I think a person like Rosemary Reuthe–and some of the more progressive voices in the context of the Christian faith–expresses more of that same hope you find in Martin. They are struggling for the same things and they sort of converge, but you need them both. You need Mary Daly to articulate the extreme suffering and pain and loss from misogyny, from sexism, from patriarchy. She expresses what is really bad about that. Rosemary Reuther expresses what is bad about it, but she also expresses what we can do about it. What resources within women’s communities shows hope. That’s the Martin and Malcolm in the women’s movement.

You find it in the gay movement too. The LBGT people. You have people who express that hope that we will one day treat same-gender loving the same way we treat heterosexual loving. Yet there are also those who articulate the despair. You can see it in the bullying, you can see it in the violence, you can see it in the persistence of the churches that do not accept LBGT people in full ministry, in full fellowship of that church and that creates a sense of despair–and that’s the Malcolm side.

But as long as people have hope, they struggle. If they only have nightmare, if they only have despair, they won’t struggle. So, even in Malcolm you got hope, because you wouldn’t have him articulating so strongly, so powerfully unless there was hope in the articulation itself. So, while King expresses the hope, he also articulates despair too. King and Malcolm have each other in each other and that’s true of all groups who are struggling for justice. You have one group that’s going to emphasize the negative side and one that’s going to emphasize the positive side, but both have both. Because it ain’t all positive and King knew that – that’s why he was fighting. And it ain’t all negative, Malcolm knew that, that’s why he was talking. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be talking to his people if there was not hope, if they, through his discourse, wouldn’t be empowered about the situation in which they found themselves in.

Hear audio of this response: James Cone on the legacy Malcolm X and MLK

JM: Are you blending scholarship with activism?

Cone: I am closer to James Baldwin than I am to Martin or Malcolm. James Baldwin was a writer, he was a preacher. He was one who bore witness to the nightmare in his prose, in his writing–that was his calling. King’s calling was not to be a writer. His call was to lead a people – that’s why he’s called the Moses of his people. Malcolm’s calling was not to be a writer – he was an orator, one who could articulate the hurt and pain of America, of black people, so clearly and so powerfully that they got up to do something about it. I am not an orator and I am not a leader of a people – I’m not Moses like King. I’m closer to James Baldwin: I write. I try to use words in ways that others can see me as a witness to what Martin and Malcolm were doing. Not that I did what they were doing, but I was close enough to it to be a witness so that the black church and the religious community in America can see that the struggle for justice does not conflict with the gospel of Jesus. It IS the gospel of Jesus. That’s what my role is, to bear witness in the theology of the gospel that is happening in the activism of Martin King and in the oratory of Malcolm X.

Hear audio of this response: James Cone on James Baldwin, Malcolm X, and MLK

JM: How do you see theology operating in the world?

Cone: I think you can see how theology affects the lives of people by understanding it as taking place and being done in the context of ministers as activists out in the world. So I see myself acting through other people, through the students I teach, like you. And I’ve been teaching at Union for 43 years so it’s a lot of students out there. I get a lot of mail and they write me all the time, in ways that you have done, to articulate the impact that my teaching and my writing has had on what they do. I’m like King, all I can do is bear witness to what I think God has called me to be, the rest is left up to God. I’m supposed to do my part, which is write and teach and bear witness to the truth, to the insight that God has given to me about the Gospel.

JM: How did you find that calling?

Cone: It started early for me. It happening before I knew it was happening. The model of my parents; they loved me. They deeply loved me. That gave me the strength to be able to speak with a kind of self-confidence. There was the Macedonia AME [African Methodist Episcopal] church which was an extension of the kind of love that I received at home, with the people expressing their confidence in me and in their belief that God had put me–and not just me, but all of us–on this earth to do something special. And then there was my segregated school, my teachers in the school who were a part of my church and the other churches – they also reinforced that. So by the time I was 16 years old and graduated from high school, I had been kept safe with the love of my parents, with Macedonia AME church, and at my school and in the community itself. When you are loved you are empowered.

So I went into the ministry when I was 16. I felt the calling, I never doubted that was what I was supposed to do. Never doubted that. What I didn’t know was exactly what form that ministry would take. I didn’t knew it would lead to me being a professor at seminary and a writer of books because I didn’t grow up in a home with books. My father only finished thesixth grade and my mother the ninth grade at the time I was home and we didn’t have books. We told stories. They told Bible stories. They told stories of people in our community. It was a story telling community, it wasn’t a reading community, it was a storytelling community. So I grew up listening to stories and telling stories.

When I got to graduate school and had to write, I didn’t know how to write and I had to learn and it was James Baldwin that taught me how to write, I kind of learned from him. And then I found my voice and it was Martin and Malcolm that helped me find that voice in the context of the black community struggling for justice in the 1960’s. And it was James Baldwin who gave me the language and the imagination to articulate the gospel that I learned in seminary.

JM: How important was a loving community to your achievement?

Cone: I could be a lot of things. I could be a genius – I’m not a genius – I could know a whole lot of things. I could be a Karl Barth of theology, I could know almost everything there is to be known, but that is not going to give me the inner self-confidence that I know what I’m talking about. Not in terms of whether I know what Thomas Aquinas said or what Luther said or what Jonathan Edwards said. No, I know what that Gospel is. I can learn a lot from Barth and Luther and they can give me clues about how they articulate that gospel for their time and their place, but they cannot be a substitute for my own voice in my time in my place. I have to do what they did, I have to do that for my time and that is not just about conceptual knowledge, that’s about a knowledge you receive through one’s encounter with God and Jesus in the struggle for justice.

JM: Contrast communities

Cone: For all times, first thing people need is love. They need to be loved and they need to love. Without love there can be no real genuine truthful struggle. King always said love is the most durable power in the world and it is. Because love can withstand any power. The paradox is that love can never be defeated. If you got love, you may be knocked down, but you’ll get up. I think what young people need today and what I needed in my time was a community that loved me. If they don’t get it at home they gotta find it from somewhere if they are to be creative participants in the world, in society, making it a better place in which to live. I think love and justice stand at the heart of what I grew up with and what I think young people today need. If they are not loved, it’s hard for them to find their way in the world. You can’t know God loves you unless there are people who love you because God’s love is expressed through people.

Joe McKnight is an MA candidate at Union Theological Seminary, concentrating on psychiatry and religion. A graduate of the Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, he is working to integrate his writing on religion with his interest in foreign affairs in Africa as well as exploration of his Southern heritage.

homepage image: James Cone at Union Theological Seminary in 1969