By Matthew Shaer

Last June, a federal judge in Washington ordered the Russian government to return to the Lubavitch-Chabad Hasidic movement a sizable library of religious texts and documents which had been seized by Bolshevik authorities in the 1920s. The library was later obtained by the Nazis, before finally ending up—in 1945—in the hands of the Red Army. By that point, Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, had fled to the United States, where he set about rebuilding his court on American soil.

The books have remained contested property ever since. In his ruling, the federal judge, Royce C. Lamberth, called the seizure by the Red Army discriminatory and pointed out that the Lubavitch leadership had received no compensation from Russia. The Russian government, for its part, has refused to participate in the legal proceedings, arguing that the library is “part of the Russian State Library’s collection, which… is indivisible.”

In a tersely worded statement this month, Russian Culture Minister Alexander Avdeyev called the claims of the plaintiff—Agudas Chasidei Chabad, the Crown Heights–based organization that oversees the entire Lubavitch movement—“provocative,” and hinted that further action could have real diplomatic consequences. The request by the plaintiff “aims to spoil the bilateral relations between our countries and to undermine the political reset,” Avdeyev said, according to Interfax.

Interestingly, this is not the first major court action involving a Lubavitch-Chabad library. In the mid-1980s, the Lubavitch community in Brooklyn was consumed by a different fight over a very different collection of texts—and unlike the case adjudicated last year by Judge Lamberth, this one pitted one descendent of Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn against another.

The story begins in the 1920s, after the original Lubavitch library was seized by the Bolsheviks. According to at least one account, the Bolsheviks later agreed to sell the library back to the Lubavitchers, but Schneersohn, never a wealthy man, was unable to meet the steep terms of the ransom.

Instead, in 1925, Schneersohn opted—with the help of several wealthy backers in the United States—to purchase the private library of a man named Shmuel Wiener, who had at one time served as the head of the Asiatic museum in Leningrad. When the Nazis began their march across Europe, Schneersohn fretted that the new library would suffer the same fate as the old. In 1939, in a last-minute bid to stave off disaster, he wrote a letter relinquishing control of the library to Agudas Chassidei Chabad, the Crown Heights–based organization that ran the Lubavitch empire.

“I have no apartment, and I find myself living with friends with my entire family in one room; consequently, I have no space for the books which Agudas Chabad loaned me for study,” Schneersohn wrote. “I would be pleased if Agudas Chabad were to take these books back.”

In 1946, with the help of American diplomats, Schneersohn managed to arrange the return of the library—the anthropologist Jerome Mintz, who has written a definitive study of Hasidic movements in the US, says the books were shipped across the ocean in a whopping 120 crates. Schneersohn himself oversaw their installation in the offices at 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, the headquarters—then and now—of Lubavitch Hasidism.

In 1950, Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn passed away without naming his heir. Many community leaders wondered aloud if the mantle of rebbe would be passed to Barry Gourary, Schneersohn’s grandson and trusted aid.

Schneersohn was rumored to have hinted as much. Years earlier, the sixth Lubavitcher rebbe had reportedly blessed Gourary with the hope “that this child grow to be the greatest of his brothers, and stand firmly on the same basis on which his grandfather is standing.” Schneersohn asked that God “grant that he tread the same path that was boldly trodden by my holy forebears, for in his veins flows holy blood that is bequeathed from a father to his son, to his grandson, and to his great-grandson.”

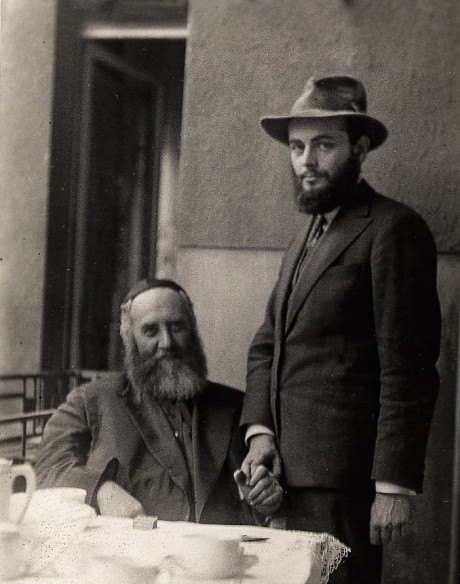

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, standing with his future father-in-law, the sixth Lubavitcher rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. ((TheRebbe.org)

The lineage, in other words, would be writ in blood: from father to son, or from grandfather to grandson. But by 1951, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Schneersohn’s son-in-law, and Gourary’s uncle, had showed himself to be a more charismatic leader than Gourary and, following a year of mourning, took his place at the head of the Chabad-Lubavitch court.

Gourary, a graduate of Brooklyn College, eventually moved to Montclair, New Jersey, and found a job as a management consultant. For several decades, Gourary had little contact with his uncle. But he often visited his mother and father, who had remained in Crown Heights in a third-floor apartment above the shul at 770 Eastern Parkway.

In 1984—driven perhaps by revenge or simply by fiscal necessity—Gourary began removing hundreds of volumes from the main Chabad library at 770 Eastern Parkway. He took old books and new ones—essays on Lubavitch theology; the testimony of past Rebbes; histories of Hasidism; biblical exegeses. He brought the books back to his home in New Jersey, compiled a computerized catalogue of the rarer volumes, and sold a stack of texts to various dealers; in the end, he made $186,000 from the transaction.

Several years later, in an interview with Jerome Mintz, Gourary claimed that Chaya Schneerson, his aunt—and the wife of the seventh Lubavitcher rebbe—had given him permission to take the books:

In 1984, my mother and my aunt had reached an accommodation on the library. They were the two heirs. My aunt had been depressed by grandfather’s death. She said: “I’m not going to read those books. Why don’t you take what you want?”. . . I took the things that had no emotional value for the movement to sell them.

But the volumes did have great value to the Lubavitch movement, as Gourary soon discovered. Over the centuries, Hasidic courts have traditionally compiled great libraries of their central texts and treatises, which are passed from one rebbe to the next. The books are keystones to the movement, and beacons back to a shared religious history.

In 1986, Agudas Chassidei Chabad filed a suit in civil court seeking to block the sales of future volumes from the Lubavitch library. “These books were not taken for sentimental reasons, but because [Gourary] wanted money. Some people rob banks, and some steal books,” Lubavitch spokesman Yehuda Krinsky said. “He’s a thief, an outright thief.”

The Lubavitchers were chastised by other Hasidim who argued that the squabble over the books should be settled—as was custom—by a rabbinical court. To bring suit in a civil court, in front of the media and the goyim, was to embarrass all in the Hasidic world.

The Lubavitchers, for their part, maintained that in the case of the library, a civil suit was a necessary evil. The Shulhan Arukh, or the code of Jewish law, forbids a Jew from taking a case before “heathen judges” unless the other litigant is unlikely to abide by the ruling of the Beis din, or rabbinical court. The Lubavitch leadership worried that Gourary, who had long ago abandoned the Hasidic lifestyle, would be unlikely to hand over the volumes on the basis of a Beis Din ruling alone. Furthermore, Gourary was in 1985 in the active process of selling off the library. If he was permitted to continue—if Agudas Chassidei Chabad waited around for a ruling that was duly ignored—the books would be scattered into the hands of dozens of different collectors. They would be impossible to retrieve.

In the spring of 1985, the rebbe went public with allegations that Gourary was looting the sacred library of Lubavitch, going so far as to call the missing books “bombs” which would detonate unless they were immediately returned to their rightful owners.

Gourary certainly didn’t do himself any favors. He continued to maintain that about a third of the books he had taken were actually secular texts. “Grandfather was a collector and he enjoyed collecting,” he explained. “Some [books] were sacred and some were not. Books that I had taken were far from sacred in the Jewish sense—the Old Testament printed by missionaries, with notes by priests in beautiful handwriting.”

Although he told Mintz that he had never been interested in the job of rebbe, the library case “reopened”—in Mintz’s phraseology—“old wounds that had existed since the death of the old rebbe in 1950.” Gourary lashed out at his uncle, noting that at “one time, Chabad was concerned with joyful worship of God.” No longer:

Nowadays the group is primarily interested in proselytizing. My uncle organized the outreach movements, and some of this is good and some is bad. He became power hungry. He began to measure his achievements. After a while he began to encourage anyone who would treat him as the Messiah.

These were incendiary charges, and Gourary quickly found himself the target of threats and intimidation. A strange car attempted to run his daughter off the road, and a group of thugs broke into his parents’ residence at 770 Eastern Parkway, leaving his mother with a fractured hand, nose, and palate. (Community leaders blamed the attack on Hanna Gourary on a deranged man, who they claimed had since escaped to Israel.) “My uncle never said anything about it, and they took this as a sign of approval,” Gourary said later. “Three weeks later, they started the case against us.”

• • •

In the fall of 1985, District Court judge Charles Sifton ruled that the library ownership issue would be resolved by bench trial. Agudas Chassidei Chabad, which alleged that the books were the legal property of the Chabad Hasidic movement, was the plaintiff; Barry Gourary and his mother, Hanna Gourary, were the defendants. The Gourarys issued a counterclaim, arguing that the books removed from the library—along with some of the volumes that remained at 770—were the legal property first of Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn and now of Barry and his mother.

News of the trial consumed the Jewish community in Crown Heights. Every day, the courtroom swelled with Lubavitch spectators, the men assembled in neat rows in the front of the gallery and the women in the back. Because so many Lubavitchers wished to watch the proceedings, a lottery system was devised by the leadership on Eastern Parkway—the winners would be ferried to and from Crown Heights in a school bus.

As Mintz noted in his study Hasidic People, there was much more at stake than the fate of the library, “a precious (if little used) archive.” There was also the issue of the rebbe’s authority, which might be seen as greatly diminished if the defendants were awarded the decision. Schneersohn had lectured regularly and loudly about the missing books; his Hasidim believed that God himself wished the whole of the library restored to the rightful hands of Agudas Chassidei Chabad.

“Gourary’s contention of familial rights was a poisonous thorn threatening the Rebbe and the well-being the community,” Mintz wrote. “Gourary’s actions could undermine Chabad and retard the spread of Yiddishkeit,” or the Jewish way of life. In this way, Judge Sifton was seen by Lubavitchers as presiding over not a secular problem but a divine struggle: the pretender versus the rightful king. A win for the plaintiffs would be proof that God was on the side of the Chabadniks.

The Agudas Chassidei Chabad case was relatively simple: a rebbe’s library traditionally belonged to his Hasidim and to the movement at large. Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn himself accepted this truth, the organization’s lawyers said. As evidence, the plaintiffs cited three letters: the 1939 note that signed over the collection to Agudas Chassidei Chabad; a missive to Rabbi Israel Jacobsen in Brooklyn, reiterating that the library belonged to the Chabad movement; and a request mailed in 1946 to the scholar Alexander Marx, requesting help in getting the Lubavitch library to Crown Heights.

“In order that the State Department should work energetically to locate these manuscripts and books in order to return them to their owners, the State Department needs to understand that these manuscripts and books are great religious treasures, a possession of the nation, which have historical and scientific value,” Schneersohn wrote. He continued:

Therefore, I turn to you with a great request, that as a renowned authority on the subject, you should please write a letter to the State Department to testify on the great value of these manuscripts and books for the Jewish people in general and particularly for the Jewish community of the United States to whom this great possession belongs.

The Gourarys acknowledged the veracity of the letter to Marx, but they claimed that the letter itself was a necessary lie on the part of the rebbe, who knew that his request would not be honored unless the retrieval of the library was seen as important to the whole of the Hasidic world. Sifton duly refuted this claim. “It does not make much sense that a man of the character of the sixth rebbe would, in the circumstances, mean something different than what he says, that library was to be delivered to the plaintiff for the benefit of the community.”

On January 6, 1987, Sifton rendered his verdict:

The conclusion is inescapable that the library was not held by the Sixth Rebbe at his death as his personal property, but had been delivered to plaintiff to be held in trust for the benefit of the religious community of Chabad Chasidism.

The defendants, Sifton wrote in his ruling, had no rights to the library. Gourary filed a cursory appeal, but the appeal was denied, and in 1987, Chabad headquarters dispatched an armored car to pick up the missing books from Gourary’s New Jersey home.

In Crown Heights, news of the ruling was greeted with a day-long celebration. The NYPD helped cordon off the cement in front of 770 Eastern Parkway, and jugs of vodka and soda were quaffed. Later in the day, the rebbe himself marched into the basement shul and joyously linked Sifton’s ruling to the 1798 release of Rabbi Schneur Zalman, the first rebbe of Chabad, who had been confined to a tsarist prison for allegedly supporting the Turks in their war against the Russians. On being freed from prison, Schneerson pointed out, Zalman had redoubled his outreach efforts—and now Schneerson, on the day of the emancipation of the Chabad library, would widen the reach of the Lubavitch movement.

Adapted from Among Righteous Men: A Tale of Vigilantes and Vindication in Hasidic Crown Heights by Matthew Shaer. Copyright © 2011 by Matthew Shaer. Used with permission of the publisher, John Wiley & Sons.

Matthew Shaer is the author of Among Righteous Men. His writing has appeared in Harper’s, Foreign Policy, and The Washington Post, among other publications. He is a regular contributor to New York magazine.