By Natasja Sheriff

Just weeks after the sentencing and incarceration in Egypt of three Al Jazeera journalists on terrorism charges, anti-terrorism laws are once again being used to jail and silence the press. This time, it’s Ethiopia’s journalists who are falling foul of a law that feeds off the global ‘war on terror’ and the pervasive fear in the west of Islamic extremism.

On July 17, an Ethiopian court charged nine journalists with inciting violence and terrorism. The journalists, including six bloggers from Zone 9, an independent collective writing news and commentary online, were arrested in April and accused of working with foreign human rights groups and using social media to create instability in the country, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Ten days later, Ethiopian authorities arrested photojournalist Aziza Mohamed for covering protests at Addis Ababa’s Anwar mosque.

But the Ethiopian government is not taking its lead from Egypt; Ethiopia’s anti-terrorism law has been used to imprison more than a dozen journalists, as well as opposition politicians and activists, since its introduction in 2009. The law has been widely criticized by human rights groups and press freedom advocates as a tool to stifle dissent.

Ethiopia shares its borders with some of the world’s most fragile states; including Sudan and South Sudan to the west, and Somalia to the east. It has cast itself as a bastion of stability in a volatile region and a key player in regional counterterrorism and anti-extremism operations. Somalia-based al-Shabaab—an offshoot of the Somali Council of Islamic Courts that merged with Al Qaeda in 2012—is considered a primary terrorist threat by the U.S State Department and Ethiopia is strategically placed to help counter that threat. Ethiopia’s 2009 Antiterrorism Proclamation (ATP) is seen as part of those efforts. As a result, Ethiopia’s government is rarely on the receiving end of international condemnation for its repressive laws, and still receives millions of dollars in aid each year. (In 2013, Ethiopia received $508.7 million in aid from the United States, more than any other sub-Saharan country).

As Alex Thurston wrote for The Revealer in 2013:

“[Prime Minister Meles Zenawi] and his successors have proven particularly skillful at positioning themselves as a “U.S. ally in combating terrorism” and positioning domestic dissidents as extremists. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have charged the Ethiopian government with using its Anti-Terrorism Proclamation of 2009, which “includes an overbroad and vague definition of terrorist acts,” to “stifle peaceful dissent.” In May, Meles said, “We are observing tell-tale signs of extremism. We should nip this scourge in the bud.” The language of the “Global War on Terror” has become useful for the country’s rulers as a domestic political weapon.”

As a result of the government’s crackdown on the press, 41 journalists have fled Ethiopia since 2009—Ethiopia is now fourth in the global ranking of journalists forced into exile, behind Iran, Syria and Eritrea. One of those journalists, Kassahun Yilma, spoke at last year’s press freedom day symposium at NYU, ‘Information on Trial.’ He described how more than 50 newspapers have been shut down by the Ethiopian government since parliamentary elections in 2005 failed to return the majority Meles’ government had hoped for. The post-election violence and government crackdowns forced many journalists to leave the country to find safety elsewhere. Yilma left for Kenya when Addis Neger, the magazine he worked for, was closed in 2009.

I spoke to Yilma, who goes by Kassa, last week, and asked him if anything has changed in Ethiopia since the symposium, and what it means for him to live in exile. Yilma currently lives in Washington D.C. where he works for ESAT, an Ethiopian news channel.

Kassahun Yilma: At that time, there were four or five journalists in prison in Ethiopia. Since then, there are a lot of changes. Ethiopia has become a very dangerous place but not just for journalists, bloggers and activists, but also for any organized citizens who are writing on social media.

Since press freedom day last year, many have fled to the neighboring countries, but the Ethiopian government is abducting journalists and opposition leaders in neighboring countries and from elsewhere—Andargachew Tsige, a prominent opposition figure, was kidnapped from Yemen airport, on June 26.

At the time, Ethiopia was number two in Africa for jailing journalists. Now the list has become very long, I don’t know how many I can mention; six bloggers and three journalists have been detained, it will be 100 days for them in prison. After that, one fellow journalist has been taken into prison a week ago on covering Ethiopian Muslim’s protests, and before this came there are two journalists who have been writing on the religious newspaper called ‘Muslim Affairs’ so that will take it to 12 total, and we are getting information that the government is still planning to imprison the rest.

How is freedom of expression in Ethiopia affected by social and digital media?

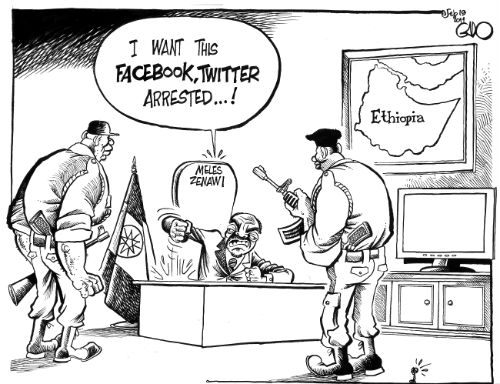

The daily newspaper in Kenya ran a cartoon about Ethiopia. The cartoon was the former prime minister giving orders to jail Facebook and Twitter. Now the government has assigned cadres on social media who can write and argue in favor of the government.

The Zone 9 bloggers and the three journalists were arrested three months ago because they blogged and they tweeted and were posting on FB consistently, almost every day. The evidence for the prosecution has been what they have tweeted and posted on their FB pages. It’s considered as evidence for being a terrorist, for working with a terrorist organization.

The three Al Jazeera journalists who were jailed in Egypt last month were also jailed on terrorism charges. How are terrorism laws being used in Ethiopia?

Ethiopia introduced its very vague anti-terrorism law in 2009 and it’s working very well to prosecute journalists, religious leaders, opposition figures and citizens. The word ‘terrorism’ is scaring all the western countries, so the government knows very well how the western countries will be convinced very easily if they mention terrorism. The Ethiopian government regards three opposition parties, Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), Oromo Liberation Front, and Ginbot 7, as terrorist organizations.

In Ethiopia, it’s not allowed to write about the opposition; if you write about them you will end up in jail because you write about ‘terrorists’. If you write about injustice or freedom you’ll be considered as a threat and that anti-terrorism law used as a tool to prosecute and to erase all journalists activities and all citizens who care about press freedom, democracy and justice.

What does it mean for you to live in exile?

It means a lot for me. I was not a very prominent journalist when I left that country, but I was in one of the very credible newspaper, Addis Neger. When the newspaper was shutdown, all of us left our country. I wasn’t ready that time, and nobody was ready, to leave that country.

I was in Kenya three years without work, but I was writing. I was trying to write and to be active on social media at that time, and my colleagues have been in different countries, in Uganda, United States and UK. We constructed an Addis Neger website and we tried to write and tried to continue our profession. The other life takes a lot of energy, because you are not settled and you don’t know what will happen. We were living in a precarious situation. When I moved to the US, thanks to [The Committee to Protect Journalists] CPJ and CUNY [City University of New York] I got a fellowship and I moved to New York.

The Ethiopian government knows that when you leave that country it will be over, because it will be about survival, and you won’t have time to write. The government is very happy if you leave.

I have family who live in fear in Ethiopia. I know that they fear. It’s five years since I saw my mom, since I saw my sisters, and I don’t call them every time, because I know that there is only one telecom service owned by the government, so all calls are intercepted. Even the internet is risky because they track you and it’s been written in the news that the government is spending many millions of dollars to buy technology from one of the spyware company in Italy.

ESAT is working for the people of Ethiopia. It’s supported by contributions from the Ethiopian diaspora. I’m very proud of working for this media, but we are in exile, no matter how the situation is we decided to commit ourselves for this media and Ethiopian people because there is no media in that country.

I’m living here but I’m always in Ethiopia because we follow up every situation in that country, and it’s getting from worse to worse.

But there are millions in a very dangerous situation in that land and many journalists and activist in jail, so this is an easy job, a very tiny contribution compared to those who are paying a huge sacrifice.

***

Natasja Sheriff is an freelance journalist based in New York. From 2012-2014 she was the Luce Foundation Fellow at the Center for Religion and Media and served as The Revealer’s international editor. Natasja co-organized the Information on Trial event with members of Amnesty International Local Group AI280.