By Ann Neumann

And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee. Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves? And he said, He that shewed mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go, and do thou likewise. Luke 10:35-37 KJV

Facts are facts but they are seldom the whole story. It’s easy for a journalist to get caught up in numbers and anecdotes but to miss the broader context. On my death and dying beat (I’m a hospice volunteer writing a book about how Americans die), there’s hardly a better example of a journalist losing his way than Ben Hallman’s recent “exposé” of hospices for Huffington Post, “Hospice, Inc.” Hallman, a senior finance reporter at the news aggregator, comes to the story of hospice from a financial perspective. He highlights the pain and suffering of several families who protest the quality and nature of their family members’ care, but proof of fraud against the US government is Hallman’s objective and to make it he focuses on hospice revenue growth across the country.

“Hospice, Inc.” has a flashy production value, with interactive maps and graphs and full-screen photos like we’re accustomed to seeing at other publications that specialize in longform journalism. Beyond the flash, though, it’s obvious from the first few paragraphs that Hallman has little familiarity with end of life care, the cultural or medical history of hospice, or standard medical practice. While Hallman may ultimately have a valid point — that hospice programs should be better regulated by the US government — he uses all the wrong reasons to explain why. “Hospice, Inc.” plays on existing misconceptions and fears about hospice–and dying in general–to argue that hospice is a flawed social service. Hallman uses several heart-wrenching but troublesome personal cases that are better examples of family grief and miscommunication, or independent cases of negligence, than they are of systemic misconduct.

It’s a critique of hospice that smacks of anti-”socialized” health care ideology: “Since Medicare is government-funded, and pays nearly 90 percent of all hospice claims, taxpayers ultimately foot the bill for this kind of fraud.” This concern for “taxpayer money” is reminiscent of the “entitlement” fights that claim basic programs and services should be paid for by charity or personal resources. This position is not only anti-poor but it removes government from responsibility for citizens’ welfare. (In fact, charity doesn’t eliminate poverty. As it turns out, even non-profit health care providers utilize the charity model when it serves their bottom line.)

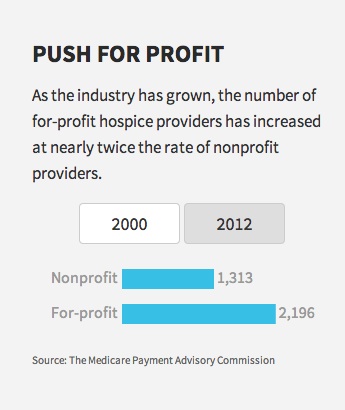

The villain of Hallman’s story is Hugh Westbrook, a Methodist minister who founded a small non-profit hospice in South Florida, later named Vitas Healthcare. Westbrook lobbied the state to legalize for-profit hospice, and later sold out for roughly $200 million in cash. Westbrook’s story falls neatly into the familiar narrative of a charitable minister turned bad by riches and many of Hallman’s examples of negligent care come from Vitas facilities, but he’s reaching for more than just the fall of a man of the cloth. Hallman’s criticism of for-profit hospices isn’t that health care shouldn’t be an enterprise for profit (it shouldn’t) but that such hospices are predominantly paid by Medicare and, thus, are making loads of money at taxpayers’ expense.

As hospice is currently structured, patients may enroll when they are diagnosed with six months or less to live. A doctor must certify their entry and at that time patients must end all curative treatments. Rationally, this makes perfect sense (and financially, it was done as a means of keeping costs down), but emotionally, it can be an especially great challenge to patients who come from religious or ethnic cultures where death is not discussed or acceptance of death is a lack of faith in God’s healing power. Sometimes the arbitrary structure of hospices causes problems for families who aren’t ready to acknowledge that death is coming.

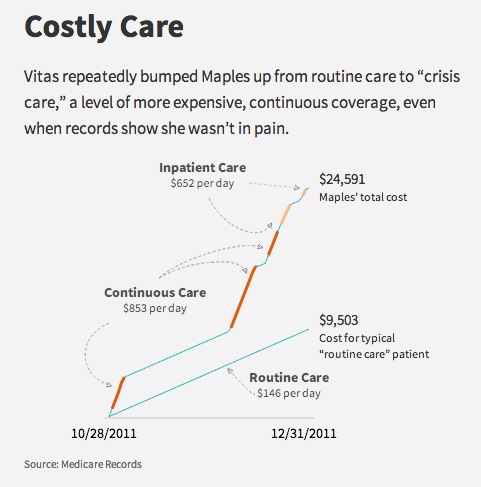

“Hospice, Inc.” is framed around one of those families. Evelyn Maples, an 83 year-old Florida resident, suffered from diabetes and other health issues. When Maples was hospitalized for a recurring urinary tract infection, the staff suggested that her daughter, Kathleen Spry, who was overwhelmed by Maples’s care needs at home, enroll her in hospice. Most of the ensuing complaint comes from what seems like miscommunication between Maples, Spry, and her son, David Dunn. Spry and Dunn didn’t understand what hospice was. They claim that they never signed a “do not resuscitate” order, a request that Maples not receive extraordinary measures to keep her alive, and that a form stating the stipulations of hospice was not in their files. If the family was not informed of what hospice does, indeed Vitas was negligent.

But the circumstances surrounding Maples’s death are not so clear. When Spry found her mother unresponsive at the hospice facility, she called Dunn who called an ambulance. This is seldom done for hospice patients; hospitals are for crisis situations and saving lives. If a patient is dying, hospitals are a place to avoid. According to the family, Maples died at a hospital one month later. They claim that hospice precipitated her death.

“Once she was on hospice, they did whatever the hell they wanted to do. It’s like she was a prisoner in their system,” Dunn told Hallman. Dunn’s anger, his call for an ambulance, his and his mother’s complaints about Maple’s medications, and Dunn’s exclamation when they found that Maples had a blood infection, “Were they just going to let her die?,” all sound like examples of a grieving family unwilling or unable to accept Maples’s condition.

Telling a patient that they’re going to die is hard. Doctors are seldom trained how to do so. If doctors haven’t helped patients to face their terminal diagnoses, neither has our broader culture which continues to treat impending death as a taboo subject. Patients and families are often left in the dark about how to plan for a death, how to assess their options, even to know what their options are. Ending curative treatment is a horrifying sacrifice for those who are still hoping for a cure.

Hallman tries to blame hospices, particularly non-profit ones, for taking advantage of our fear and lack of information by enrolling the ill-informed, by pressuring the hesitant or even the healthy. And while I grant that financial incentives certainly lead hospices to aggressively seek enrollments (this isn’t all bad!), the issue is much more nuanced. As a hospice volunteer, I’ve encountered patients and families (both in in-hospital facilities and at home) who are still hoping for recovery, still receiving get-well cards from friends, still bargaining with their bodies and their gods for the gift of extra, miraculous years.

Medicine may be a science but it’s not exact. When a doctor determines that a patient will likely die within six months, it’s an approximation. What enrollment really means is that there is no longer any chance that a patient’s illness can be cured. Hospice currently puts a limit on the time a patient can be cared for in the way they want, outside a “do everything” hospital setting. It’s a false and inexact way to mete out one’s health care needs and a symptom of our inadequate and deeply flawed health care system.

Hallman criticizes increasing lengths of stay in hospice and poor pain management, but here too he shows a lack an understanding of how unpredictable the human body (and the human will) can be. It’s hard to trust his examples of egregious behavior when he knows so little about what medicine can and can’t predict. He assumes that the growth of hospice is the result of nefarious behavior on the part of hospice directors, rather than a positive development or even one driven by the growing elder population. Hallman also misses the opportunity to discuss the broad changes in how health care is delivered in the US, as independent hospitals are gobbled up by large health management organizations (HMOs).

Hallman rightly notes that part of the increase in hospice enrollment has to do with admittance of non-cancer patients, those with long-term diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and kidney disease. As hospice has grown, patients have learned that hospice isn’t just for those dying of cancer. But from a care perspective, this is a good thing. For patients who don’t have the money for assisted living but aren’t critical enough for a hospital (or are being pushed to leave one) hospice provides professional care when they wouldn’t otherwise get it. Instead of attributing this increase of hospice patients to a problem with hospice enrollment, we should view hospice as imperfectly meeting the needs of those who’ve fallen between the cracks in our care system.

Hallman also targets perceived drug abuses in order to show that hospices are incompetent, but he has little understanding of how such drugs are used, how unpredictable bodies can be, and what grief can do to families watching the process of dying. Hallman writes:

“In one example described in court filings prosecutors allege a Vitas patient was given crushed morphine, even though she wasn’t in pain. The morphine treatment continued even after the patient showed signs of having a toxic reaction to it–even seizures, prosecutors claim. Vitas then elevated the patient to its crisis care service to deal with the reaction it had caused, according to the lawsuit, at a cost of four times the standard rate.”

Morphine has various uses. It can alleviate pain, yes, but it is widely used in a hospice setting to make breathing easier. (Maples suffered from a disease that afflicts former smokers.) Unless a patient has prior experience with morphine, it’s hard to know whether a reaction will occur. He continues:

“In lawsuits and complaints with state law enforcement officials, hospice families claim their directives were ignored and that loved ones received too many medications, or not enough.”

Of course, once signs of a negative reaction are evident, increasing a patient’s care service is justified. The needs of a dying body can change by the hour. To families who don’t understand what death and dying look like, how it can happen, these adjustments and changes can look like incompetence. Families are disoriented by grief and uncertain of what to do. To a journalist writing about such things, lack of understanding can lead to false conclusions.

Most disturbing is the fact that Hallman never considers Evelyn Maples’s wishes, if she gave consent for hospice care, if she asked for a DNR. Her wishes could have been different from those of her daughter or grandson, something only her doctors could know. According to records, she did tell a nurse that she no longer had any good days. Could she have been shielding her family? Hallman never considers medical confidentiality. Maples’s story is tragic, but as Hallman tells it, it doesn’t prove that Vitas did anything wrong.

By framing the story around Maples as an example of fraud, Hallman fails to make his case. Hospice programs provide a service that is desired by most patients, that is wildly popular, and that is frankly, in my experience, more caring than other institutional alternatives. Because hospice fits under the Medicare payment structure, it’s available to many low-income patients. And, as recent studies have shown, enrollment in hospice (or more specifically, ending curative treatment) helps patients to live longer. Two more months of life at home, surrounded by friends, with good pain management? I’d say yes.

To many, hospice is the model for the future of health care, a more holistic approach to treating patient illness, pain and grief. And for supporting care-taking and grieving families. Many experts have long said that US health care is in crisis and that the Affordable Care Act is only a short term fix; that our aging population and the exponentially increasing costs of health care will force us toward single-payer, national coverage.

From the hospice trenches, it’s hard to see increased enrollment, even if it extends beyond the arbitrary and impossible six month limit, as clear fraud. Yes, companies that are dishonest, that over-bill, that don’t provide good care should be more closely regulated. And yes, medical malpractice is a tragedy that must be addressed. But Hallman never examines why patients are staying longer and he never contextualizes the claim. In 2013, more than one-third of hospice patients either died or were discharged after a mere seven days. Across the hospice world, the short length of patient stays is a dire concern, not their increasing length.

There’s a reason I’m being so critical of Huffington Post and Hallman. They’ve invested incredible amounts of time and labor into a hit piece that doesn’t make its case effectively (read the comments). More importantly, there are ethical ramifications to publishing a story like this. While I agree that better oversight is important and that, if confirmed, the experiences Hallman notes are tragic and should not be ignored, it’s stories like “Hospice, Inc.,” that perpetuate a fear that is already too prevalent. They prevent patients and families from facing the facts of dying, from being better-informed decision makers. “Hospice, Inc.” fails to prove that there’s a great systemic problem in how hospice patients are treated and it fails to present readers with a greater understanding of how best to care for patients as we die. It’s a shame that Huffington Post didn’t take the time to do this right.

***

“The Patient Body” is a monthly column about the intersection of religion and medicine. Prior columns can be read here:

Your Ethical and Religious Directives

Hospitals and the Pretense of Charity

***

Ann Neumann is a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Religion and Media at New York University and contributing editor at The Revealer and Guernica magazine. Neumann‘s book about a good death, SITTING VIGIL, will be published by Beacon Press in 2015.