By Maurice Chammah

The Baptist preacher Lester Roloff founded the Anchor Home for Boys to help troubled teenagers get their lives back on track. Nearly fifty years and three states later, the school that bears his name has transformed dramatically and escaped the allegations of abuse that once plagued its reputation. But many of its alumni are still haunted by questions.

TheFarm :: Inside the Anchor Home for Boys from blue cabin studios on

Vimeo.

Aaron Anderson’s dad had said they were going to the beach. Along with Aaron’s mother and younger brother, they were packed into the family car, careening past the sand and scrub of the Texas Gulf Coast on a spur of the moment vacation that so far had included an amusement park in San Antonio and the Corpus Christi aquarium.

It was 1998, and 16 year-old Aaron was still coming out of a rebellious stage. He had been taking drugs and sneaking around with his girlfriend. His parents tried to home-school him. He tried to run away. His parents relented, allowing him to attend high school in Burleson, their rural town south of Fort Worth. That seemed to improve things. The family was getting along better and better. This vacation was the proof.

Which was why things didn’t add up when his father started driving away from the beach.

Before he thought to ask where they were going, they had arrived. It was a small set of buildings surrounded by farmland, just outside of Corpus Christi. “This is where you’re going to stay for the next year,” Aaron remembers his father saying. He remembers his brother crying and his mother staying silent. He remembers an older man walking up and telling him to step out of the car.

When Aaron refused, the man left and returned with three more men. They yanked open the door and began pulling him out by force. “I was screaming at the top of my lungs,” Aaron told me. “You put up a fight. You want somebody to hear.”

Aaron learned that he had been taken to the Anchor Home for Boys, which offered a year-long residential treatment program for teenage boys with various behavioral issues. His parents had heard about it from their pastor. At Anchor, Aaron would read his Bible every day and be kept under close watch. Hundreds of boys had gone through the school and spoken glowingly of having their path corrected in a safe, warm community.

As his parents and little brother drove away, Aaron was taken inside. “The rest of that day,” he told me, “was pretty much non-stop beating.” The violence, he said, continued for weeks, until eventually he was put in charge of other boys and in turn oversaw harsh physical discipline.

When Aaron arrived at the Anchor Home, the institution had already been through a long and winding history of battles with the State of Texas over allegations of abuse and a lack of oversight. After he left, the home would move to Montana and again to Missouri, where it currently operates.

Throughout that history, one finds allegations of abuse from some former students. One also finds denials from other students and from staff, who say those allegations are exaggerated and that for the most part the school provided an encouraging, positively transformative experience.

Eventually this back-and-forth gives way to something more complex. Many alumni describe conditions and practices that fall into a grey area between discipline and abuse and simply not feeling right. They can’t always decide whether what they experienced was wrong or illegal or valuable or just inexplicably strange. One said to me, “I’m glad somebody can hear me, because it’s bananas.” Another said, “It was crazy. It’s hard to explain or to tell anybody.” Aaron Anderson said, “They have their own culture there. You never leave it.”

Hundreds of residential programs around the country — some religious, some not — promise to improve the behavior of teenagers through strict discipline or ‘tough love.’ For the most part, these programs face little to no regulation from state and federal authorities, and that creates the conditions for abuse, which has been well-documented by journalists throughout the years.

But the lack of regulation also creates the conditions for all manner of practices, punishments, and activities that are not abusive, not illegal, and not ‘wrong’ by any sort of official measurement but still may make some observers queasy and may have had negative psychological consequences on the teenagers who went through them. There’s no scoop here; just an endless stream of knotty questions. For many of the boys who went through Anchor, these questions — What really happened? Should it have happened? — are still unresolved.

+++

By the time Lester Roloff founded the Anchor Home for Boys, he had already built a national reputation for helping men and women cast off their self-destructive habits through faith and prayer. Born on a family farm in rural East Texas in 1914, Roloff was raised in a strict Baptist tradition and decided from age 18 to spend his life preaching. He picked cotton to pay his college entrance fees at Baylor University and brought Marie, his Jersey cow, to the campus, selling milk to pay for room and board. “I had to guarantee three gallons a day,” he later wrote. “That was a step of faith!”

By his senior year, Roloff was already preaching part time at the country churches, and after a few years at a seminary in Fort Worth, he became a regular on the revival circuit. His style was fierce and uncompromising. This was old time preaching, full of whispered pleas and shouted commands. In the middle of sermons, he would spontaneously burst into gospel songs.

After setting up Roloff Evangelistic Enterprises in Corpus Christi in 1951, Roloff’s ministry grew to include a daily radio program and — once he obtained a pilot’s license to fly his own small plane — regular engagements around Texas. He broke away from the Southern Baptist Convention in 1956, but his church was expanding, and that year he opened the City of Refuge, a residential treatment facility for men who had trouble with drugs, alcohol, and crime. “Some have suggested that we appeal to the state for funds, but [this] is a work of faith and there must be no strings attached that would keep us from preaching a full gospel and ministering to the spiritual needs of people,” Roloff said at the time.

In 1958, Roloff built a houseboat off the gulf coast near Corpus Christi, which became known as the Lighthouse, where men with drug and alcohol problems were sent either by judges or by their own choice, and where isolation from society was stressed as an effective means of breaking old habits. A similar home for women followed several years later. When a pregnant 15 year-old girl came for help, Roloff founded the Rebekah Home, which would take girls under 18.

The Anchor Home for Boys followed in 1967. Like the Lighthouse, it was isolated, set up on an old Air Force base in Zapata, Texas, a tiny town along the Mexican border. Where the men of Lighthouse had chosen to go there, now Roloff was accepting boys brought by their parents, often against their will.

Expanding to youth meant, among other issues, that the state had a more immediate interest in the home’s activities. The Texas Department of Public Welfare demanded that Roloff obtain licenses for the Rebekah and Anchor homes. He refused, arguing it would be a violation of the separation between church and state.

A long, protracted battle ensued. Roloff would spend several short stints in the Corpus Christi jail. The Anchor and Rebekah homes would be closed down and reopened throughout the 1970s, occasionally dispersing its students to other homes in Georgia and Mississippi and then returning them to Texas as the state’s supreme court, legislature, Department of Human Services, and Attorney General all took differing stances in the debate over whether Roloff needed licenses in order to care for the well-being of adolescents.

Through his radio sermons, Roloff gained widespread support, at one point attracting over 10,000 people to a rally in Dallas called “Save Our Nation.” He started calling his battle the “Christian Alamo.” He directed hundreds of followers to link arms in a circle around his People’s Baptist Church in Corpus Christi to keep state investigators out. Those investigators were bolstered by increasingly urgent reports that the children in these homes were facing horrific forms of physical and even sexual abuse.

+++

One of the boys in that circle of arms around the church was Jeffrey Barnes. Brought at age 13 after his mother had died and his father remarried, Jeffrey never really understood why he was taken to Anchor. On his first night, another boy tried to fondle him. “I hit him, “ Jeffrey recalled. “Another kid came at me. I picked up a wooden chair and put it across his head.”

The staff discovered what had happened and beat Jeffrey. From that day forward, the punishments never ceased. He’d be paddled with ten to fifteen licks for all manner of major and minor infractions. “They beat you for any little thing,” including mentioning any hint of the abuse to your parents over phone calls home, which were monitored by the staff.

In the 1970s, paddling was not far outside the norm of what parents around the country might do to kids who misbehaved. But things went further. Jeffrey said he was locked in a room and handcuffed to a bed-frame for hours on end, as a Roloff sermon was played through speakers. Staff members, Jeffrey said, would shoot BB guns at the boys, forcing them to run around to escape the little metal pellets. “Some of the men made a game of torturing us.”

In between the punishments, Jeffrey got used to the daily routines. The boys woke up at 4am to milk the cows, just as Roloff had done in his youth. They picked watermelons, and in the winter they burned tires to keep the field from freezing over. They learned from Christian educational workbooks, which Jeffrey learned how to cheat his way through, and memorized large portions of the King James Bible, which Jeffrey couldn’t get around and can still recite to this day.

He got used to the feeling that escape was impossible, since the school was surrounded by Mexican desert on one side and American desert on the other, but he also knew that if he could get word out to his family about he extent of the abuse, maybe he’d get to go home. He realized that the only boys who were allowed off school grounds were those in the choir, which toured to churches in nearby cities. He joined up. At a concert in San Antonio, he finally saw his stepmother and told her about the abuse. Shortly after, she pulled him out of the home.

Now in his 50s, Jeffrey reserves far more hatred for these staff members than for Roloff himself, whose knowledge of Anchor’s worst punitive excesses remains a mystery. “I think Brother Roloff’s intentions were good,” he said. Still, he knew that Roloff, in defending himself in a state hearing, had said, “Better a pink bottom than a black soul.” Attorney General John Hill had famously responded that he was more concerned about bottoms “that were blue, black, and bloody.”

+++

Lester Roloff died in 1982 when his private plane went down. “The month after Roloff died stuff really descended into chaos,” recalled Robert Nicholson, who attended Anchor shortly after Jeffrey. Anchor moved from Zapata to join the other Roloff homes near Corpus Christi. According to Robert, the numbers grew, and the school began accepting boys with more severe psychological problems.

Like Jeffrey, Robert remembers older boys “taking great joy in having attention put on new ones.” They’d watch as boys were beaten with “paddles, belts, whatever object could be made into a hard surface and used for beating somebody on the ass.” One time, Robert had to “chew up and swallow soap because I looked at a girl too long in church.” On another occasion, “Somebody stole a Snickers bar from a charity basket. The whole home was on their knees in the hallway being paddled and passing out from pain.”

At one point, Robert escaped and made it to Corpus Christi. “The cops found me and saw my ass was black and blue and bleeding,” he recalled. “The Corpus Christi jail had the best chili. I was so happy to be in jail.”

As the State of Texas continued to put pressure on the home to get a license or close down, Roloff’s successor Wiley Cameron defended his practices, telling the state that they had never abused the boys, and that harsh discipline was necessary to help them divert from a sinful path. “Our homes,” Cameron said in an official statement, “have dealt with the most desperate cases imaginable of truly ‘terminal’ young people” (Roloff too liked to use the word “terminal” to describe his wards). “We have tried to help them with love, with understanding and with the discipline which will help them get their lives in order and to cease being a prey upon others.”

After more negative press and allegations of abuse, the Anchor Home eventually shut down. Wiley Cameron continued to lobby the Texas Legislature to create an alternative method of accreditation that would allow him to reopen in Texas without regulation from the Department of Human Services. In 1997, he got his wish.

+++

When Aaron Anderson was dropped off by his parents in 1998, he became a member of the inaugural class of the revitalized Anchor Home in Corpus Christi. The year before, the Texas Legislature had passed a bill allowing faith-based children’s homes to be overseen by the newly founded Texas Association of Child Care Agencies. Wiley Cameron, the head of the Roloff homes, served on the association’s board of directors.

After Cameron reopened the Anchor Home, it took almost no time before journalists and liberal activists, familiar with the Roloff homes’ earlier history, started looking for signs of abuse. Then-Governor George W. Bush had pushed the faith-based initiatives legislation in Texas as a prelude to his run for President, hoping to lure evangelical voters. With the Roloff homes, liberal activists had found a sensational cautionary tale about what happens when the state gives too much leeway to religious institutions. Where Roloff had once been cast in the role of antagonist to a secular state government, now his homes were entrenched in the culture wars, battling for the heart of that government. Responsibility for the abuse at these homes could now be pegged not only on a handful of religious eccentrics, but also on the most powerful politicians in the state, and perhaps, if Bush became president, the country.

Of course, Aaron had no idea about any of this as he settled into life at Anchor. He’d tried to escape on his second day and fell into a mud pit before he got too far away, which led to more beatings. “My ribs hurt for a couple months after that,” he said. “Who knows if I cracked or bruised one— They never took me to a hospital.”

Over time, he learned to avoid getting hurt. The main way to do that was to stay totally silent. When he arrived at Anchor, Aaron told me he was placed on “verbal probation.” He was barred from speaking to anyone except for staff and a single “keeper,” and could only speak to them when instructed. Later students would use the term “guide student,” and the practice has lasted until today, defended by staff as a good way to break old self-destructive habits that the boys bring to Anchor.

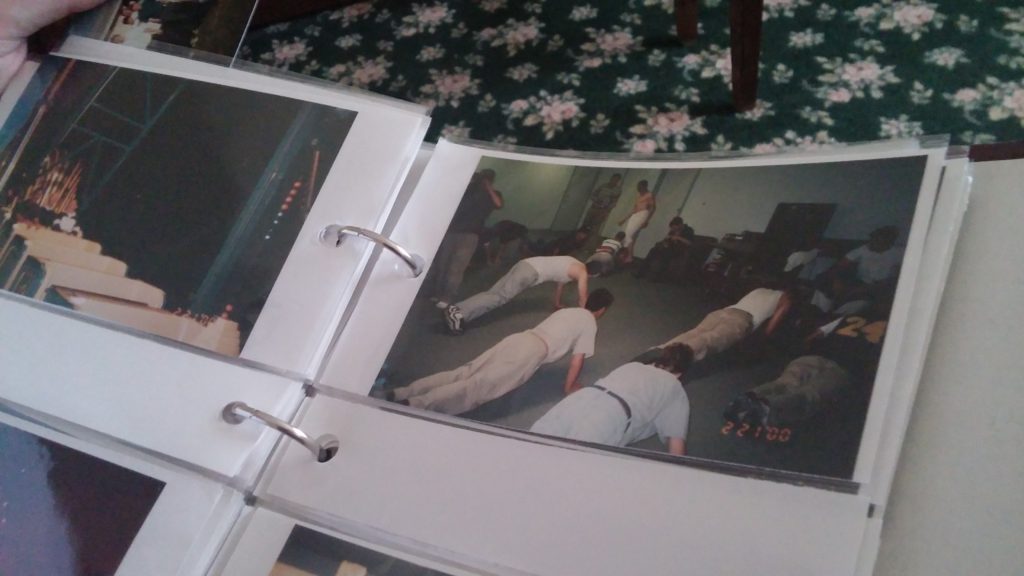

Aaron told me that the punishments — for looking at others, for speaking to anyone outside of the approved structure — included hits and kicks from staff or from men at the Lighthouse home next door. He described being forced to kneel on rice for hours while weights — usually heavy books — were added to his outstretched arms. If he was put on “Red Shirt,” a special punishment designation whose numbers ranged from a few to as many as 20 other boys, he would have to run for hours on end, and be kicked if he fell down. He would have to spend hours digging holes and filling them back up again.

Roloff, though he had died 17 years earlier, was a constant, ghostly presence. “They had his picture everywhere,” Aaron recalled “They talked about him all the time.” Every few months, the boys would be woken up late on Saturday night. They’d walk to the chapel and kneel while Roloff’s sermons were played over speakers. “I felt like I was a prisoner in a cult, to be honest,” Aaron told me. Over time he learned how to talk the talk. “If you pretend with a group of people long enough it feels real.”

Nearly every one of the alumni I spoke to described a moment when the line between pretending to believe in the Anchor system and actually believing in it started to blur. A student from around 2008, going by the name “Drake” on an online discussion forum wrote:

“My peers who were there for reasons usually far worse than mine scowled at me. Treated me like I was the scum of the earth and showed no sympathy even though however long ago they were in the same position as I. Then without my realizing it had happened, I had become what had bewildered me. I had become the one slamming kids into the ground and forcing their noses onto surfaces. At the time I thought I was doing what was right and wanted nothing more than to please my superiors. I was helping to uphold the very system I thought so unjust.”

Less than a month after Aaron was allowed to talk to other students, he was put in charge of punishments. Instead of sitting in the classroom, where other kids had self-paced Christian workbooks, Aaron was out on the track, watching kids run endless laps and kicking them if they fell down from exhaustion.

His sole education was Bible memorization. If he succeeded in his memorizations, he might be treated to a John Wayne movie in the lunchroom or a short trip to a carnival with other “crew leaders.”

Fifteen years later, Aaron regretted how he had used his authority. “I get emotional, shaky when we talk about this,” he told me. “I’m constantly questioning how I felt back then. Did part of me enjoy it?”

***

As Aaron left in 2000, pressure was mounting on the school to open itself to scrutiny. News stories had been coming out about Anchor’s sister school, the Rebekah Home, where girls were telling stories of being whipped, beaten, bound with duct tape and locked in isolation cells with Roloff’s sermons blaring over speakers. In June 1999, Texas Child Protective Services issued findings of physical abuse and medical neglect at the Rebekah Home and banned Wiley Cameron’s wife Fay Cameron, the head of the home, from working with juveniles in Texas ever again.

Not long after, scandal hit the Lighthouse, the Roloff home that housed young men too old for Anchor. Aaron Cavallin and Justin Simons were 16 and 17, young enough to attend Anchor, but placed at the Lighthouse, for men 18 to 25, due to their size. Cavallin and Simons were overheard talking about running away and a staff member named Allen Smith punished them by tying their wrists to the back of a pickup truck and forcing them to run through brush and thorns barefoot. Then he forced them to dig at the bottom of a pit 15 feet deep. Simons told investigators he was there for more than 16 hours, and that he asked to take a break and was told he would have to jump across the pit. When he tried to do so, he fell in, spraining both ankles. Other students told investigators that the boys were instructed to throw food and compost into the pit, and that a pipe spewed sewage at their feet. Cavallin told me that a boy had urinated into the pit.

Allen Smith was found guilty of “unlawful restraint” a year later at trial, and ordered to complete a year of probation and 150 hours of community service. Soon after, Wiley Cameron resigned from the Texas Association of Christian Child Care Agencies. The national press swarmed to the story in order to discredit presidential candidate George W. Bush’s faith-based initiative program.

The Corpus Christi Caller Times, the city’s paper of record, showed ample sympathy to Cameron’s cause. “Youths find structure at church homes,” was the headline of a Sunday feature story several weeks after the pit incident, which described how “residents of the homes and others” had “defended the ministry’s work following recent abuse allegations made by two young men.” Anchor was barely mentioned, except to provide a vivid image. “About 20 boys clad in white shirts, red ties and khaki pants finished up their school work for the day, stood in a line and sang a religious song,” wrote reporter Dan Parker. ‘Run if you want to, run if you will,’ the boys sang, in part. ‘But I came here to stay.’”

Day to day leadership of the Anchor Home was handed over to a 25 year-old named Dennis McElwrath, who decided to move the facility out of Texas. He reestablished the school as Anchor Academy and set up on two different sites in Montana before financial problems led him to relocate to Vanduser, a tiny cotton-ginning town in southern Missouri, where he operates it to this day.

+++

Here are some of the punishments and general policies described by graduates of Anchor Academy during its years in Montana: spankings with a wooden paddle, hours of physical exercise in freezing weather with improper clothing, being prohibited from speaking to anyone other than a direct superior, spending eight hours on a Saturday scrubbing a single spot on the floor, eating peanut butter sandwiches for weeks at a time and having to carry them around in plastic sacks if you failed to eat them, having to hold a broom above your head while your feet were tied together, so that any movement required hopping around. Graduates described having to write hundreds and even thousands of repetitive lines of text by hand until their hands cramped. If you got behind, they said, you would be forced awake for thirty minutes every hour of the night to stand and write lines, which amounted to sleep deprivation.

“That place brainwashed, whether they intended to or not, an ideology, a dogma, and a fear of physical and eternal punishment if you didn’t comply,” said Michael Quinn, who attended from 2002 to 2004 in Havre, Montana. On the lingering effects of verbal probation, he said, “I ran out of things to talk to myself in my head about. I couldn’t remember words. There was nothing up there in my head.” On the system of authority, he said, “I always to this day have trouble looking at people. I look at the ground.”

“Put your back against the wall and put your leg at a ninety degree angle and raise your arms,” he told me of one punishment. “If you drop your leg I’d punch you. If you drop your arms I’d punch you. If you say no I’d punch you. I’d say that’s torture. As a 16 year-old kid viewing this stuff, all I know is that it felt wrong.” When he described kids whose parents seemed like they might never come back, he broke down crying. “Nothing too terrible happened to me,” he said. “I played the game as much as I needed to.”

Michael’s memories were echoed by those of his friend, Samuel Speights, who attended from 2001 until 2003. Sam’s father had attended Anchor in the 1980s. Sam had been skipping school and doing drugs. “My mom took me there because she wanted me to graduate high school,” he said. “She had pretty good intentions for me. She didn’t want me to fail in life.”

As an older student, Sam said, he rose quickly to become a leader. Even still, he wasn’t immune from punishment. One time, a student directly under his supervision had to go the bathroom in the middle of the night. The doors of the dorm-style room were locked, so Sam woke up a staff member. The next morning, Sam learned that he had lines to write.

As with his predecessors, Sam described occasional rewards, like screenings of action films. The food was filling and tasty. The system didn’t guarantee you would have a miserable experience.

In fact, other Anchor alumni say these punishments were wildly exaggerated by boys who were so undisciplined that getting up before noon could be spun into an act of torture. Sam and Michael’s memories of Anchor, as well as those of Aaron Anderson, contrasted irreconcilably with those of Daniel Minnick, who started in Corpus Christi in 1999 and then returned as a staff member in Montana intermittently until 2003.

Daniel described Anchor as a “watered-down” version of the military, which he later joined. Getting up early, exercising intensively, and staying silent around other students were all reasonable methods to help kids get on a straight path. “We had it easy,” Daniel said. “I almost think that some of the folks that see it in a bad light never woke up to adult responsibilities.”

Was there violence? Daniel said, “Obviously you put those kind of youth in an environment with each other, there’s going to be tension. One student is going to punch another student. Was that tolerated or perpetuated by staff members? No. But were there times I recall somebody got punched in the face? Sure. Boys will be boys.”

Many recent alumni of Anchor Academy in Montana and Missouri have described their experiences in online discussion forums, offering advice to parents of prospective students. Most of these alumni either vigorously denounce the school’s practices as abuse or write in glowing terms of its ability to save troubled kids.

A few, however, lie somewhere in the middle. Jordan Harrell was at Anchor for two years and four months between 2003 and 2005. “What I do know is that they do love their students,” he wrote on one online forum in 2009. “Just do your research before sending your children there.” He credited Dennis McElwrath with incremental positive change. “If you choose to follow the rules as your told, you can escape with a very positive experience.”

But as his posts multiplied (“Wow this brings back so many memories”), Jordan’s anecdotes slowly grew more extreme. He described a boy tied to a five-foot rope and dragged around, a boy beat up nearly every day for a year, a boy on peanut butter sandwiches for months who on one occasion watched the staff feed his sandwich to a dog.

Less than a year later, Jordan posted on a different forum, going into more detail. He described the systems of verbal probation and guide students, and said that on occasion his guide gave him conflicting instructions, and then punished him for following one instruction instead of another. “After that, he told me to bend over and put my nose on the bunk. In this position, you must keep your legs straight, and bend over to put your nose on something. Try it with a table for instance. After standing in that position for long enough, it will bring tears to even the strongest of people.”

Where less than a year before, Jordan had been measured in his criticism of the punishments, he now revealed a deeper level of trauma, as if the memories were a scab he had picked raw. “I saw things that would make parents cry. Still to this day I feel terribly guilty about not trying to do more.”

“Some people will read this and try to say that I am lying, try to say that I don’t know what I am talking about,” he continued. “I dare someone to say that to my nightmares, tell it to the hundreds of boys who have gone through there and now have some sort of anxiety problems.”

One theme that pervaded every interview about Anchor, particularly after its rebirth in the late 1990s, was the idea that the program fostered a very particular subculture that outsiders would find perplexing. Sitting in a tiny coffee shop in Modesto, California, Samuel was anxious to describe the abuse, letting story after story spill out. But he seemed even more anxious to say how strange it all was, interrupting himself constantly to say, “It’s so crazy, It’s so crazy,” as if he had once convinced himself that none of it had happened, and was still wondering what exactly was wrong about the situation, if anything at all.

And to illustrate that point, Sam told me that Dennis McElwrath, or Brother Dennis as they call him — the current head of Anchor Academy, who I would soon meet — had a select group of boys come to his room each night. Those boys would rub his feet and serve as informants on what was happening outside of his gaze. Michael corroborated this story. “They tried to get me to rub feet,” he told me. “They woke me up in the middle of the night.” He was sleepy and confused. “Then the kid came back and said ‘nevermind go to bed.’”

Michael paused and then spoke, as if responding to this late-night silhouette of a boy from a decade before: “You’re damn right! That’s the weirdest thing ever!”

+++

Anchor Academy and Anchor Baptist Church sit on one corner of the main intersection in Vanduser, Missouri, by far the nicest buildings in a town of decaying wooden houses and vast cotton fields. Dennis McElwrath was standing on the front porch, chatting with a group of young men when I drove up on a recent Tuesday. We’d spoken on the phone. “How did you target us?” he had asked me. I said I was interested in the legacy of Lester Roloff’s homes. “I can’t speak for the Roloff homes of the 80s since I was barely born,” he said, but he agreed to let me come visit, adding, “I’m not looking for publicity to get more students. We are full, turning people away…We’re overwhelmed with calls.”

McElwrath has a boyish, ruddy face and a bald spot he likes to point to when describing some of the more stressful moments working with boys. He stressed that the new Anchor Academy had no contact with Roloff’s church, and said he tried to increase community involvement. He introduced financial literacy classes and set up accounts so the boys — he calls them “the fellas” — could get paid for work at the cotton gin and other projects, taking their savings when they left the home.

Over a dinner of goulash, string beans, and garlic bread, McElwrath said that the two major issues facing young men today are the fracturing of families and the emphasis on status — physical, social, financial — which makes them feel inadequate. He mentioned the high rate of teen suicide. “They get to a place where they don’t want to face it anymore. We want a young man to come here and be safe, to know that they’re not going to be made fun of or ridiculed.” He said that assigning guide students to newcomers and strictly managing whom new students can talk to is part of the process of “putting the past in the past.” The guide students are supposed to exert “positive peer pressure” and the enforced silence keeps the new boys from “reinforcing old addictions.”

McElwrath often resorts to analogies that call to mind the moment in a sermon when a pastor uses a real-life example to illuminate a biblical verse. When we finally got to disciplinary policies, he was not defensive about the accusations of abuse we had both read on the Internet. He chose the analogy of traffic tickets, which if unpaid may lead to higher fines and then jail time. Small disciplinary infractions had minor penalties, he said, and the vast majority of the time that was enough.

He said that the practices Michael, Samuel, Aaron, and Jordan described were consequences given to only a tiny percentage of students who simply would not follow the rules, and that many of the most intransigent boys made a game of taunting staff members. He pointed to his bald spot and described an instance where one student had to run a single lap on the track as punishment and instead stood in place, ridiculing McElwrath as he was bitten by mosquitoes. “There are kids with unbelievable amounts of stubbornness,” McElwrath said. “There are times where you’re worn to a complete frazzle. To them it’s a game, to us it’s like, ‘Will anything get through to them?’”

He said the practice of making the kids sleep in intervals and write lines through the night was short-lived because it exhausted the staff and was only ever used for a few of the most obstinate boys. “None of it was unreasonable. It would just come down to a battle of the wills.” He said nobody had to eat peanut butter sandwiches for more than five days, and that they were also given carrot sticks and an apple. Even still, some of the kids “wouldn’t eat the peanut butter and would say ‘I don’t care. I’ll just starve to death.'” Usually, he said, they’d give in pretty quickly and go back to eating food.

“A lot of the fellas that would be very complaining, I think you’ll find, are not willing to take responsibility for their lives,” McElwrath said. “There were a select few who were always the victim, whose problems were always the result of somebody else.” In order to reduce the number of boys like this, he increased the minimum age and started turning away kids whose problems were so severe that he felt the program could not help them.

“I’m not going to tell you there haven’t been mistakes made,” he said, giving credence to the criticism that he does not have extensive training in counseling. He mentioned Anchor Academy’s only brush with the law, in 2004, when an employee named Justin Peterson was charged with fondling a 15 year-old student and was promptly fired. “There is no substitute for experience,” McElwrath said. “If you do things the wrong way a few times you’re apt to learn the best way to do it, and we’re always open to change in the program overall…I’m not going to have doctor’s degrees on the wall, but after 15 years we’ve been around the block enough times and know the heart of young people.”

After dinner, McElwrath gave me a tour of Anchor Academy, and I saw the perfectly-made cots, the cozy living spaces, the schoolroom with its individual desks and a school store with snacks you pay for with good grades and behavior, the clean and unadorned chapel, the vast stores of food, much of it fresh. All around me, boys were doing their evening chores: sweeping, cleaning plates from dinner, loading laundry by the armful. A few boys were on the phone with their parents. They nodded and smiled at McElwrath and I as we passed by. We walked outside, where a boy who had bought a car with money he had personally earned working at the cotton gin was cleaning the vehicle with a sponge and soapy water. McElwrath had helped him pick out the car, and he beamed with a father’s pride.

We climbed into a truck and McElwrath drove me several blocks to the cotton gin and the pond where the boys go swimming up to five times a week. McElwrath described the boys and the staff as a family with their own particular habits and quirks. “You may certainly see things that appear as strange, and you can ask me anything,” he said. As an example, he said I might see one boy having a friend work the knots in his back, since he had been to the doctor for these knots and that was the prescribed treatment.

Then, without prompting, McElwrath told me that he has a similar problem. “I have a lot of trouble with my feet; my feet will get so knotted up,” he said. “Sometimes guys will be a blessing and work on some of the knots in my foot.” The activities might seem strange to an outsider, he said, but “it’s not uncommon when you live together…you’re with them all the time, it’s like a family.”

+++

I started reporting on Lester Roloff’s Anchor Home and Dennis McElwrath’s Anchor Academy expecting to find accusations of abuse and denials of abuse and expecting the accusations, even the sensational ones, to appear to be more credible than the denials. This would be one more story about injustice, in which places designed to help young people ended up hurting them. Bearing that out, several of the men I talked to seemed truly haunted by their experiences. One broke down in tears. Another said he got “shaky” when talking about his memories.

The pervasiveness of abuse at residential homes for troubled teens has been well documented. In 2007, a series of deaths at residential programs for teens led to an investigation of teen deaths and “thousands of allegations of abuse” by the Government Accountability Office and a series of proposals for reforming the regulation of teen homes that since then have failed in Congress. In 2009, House Resolution 911, which would have created a national database of programs and increased access to abuse hotlines for teens, passed the House but did not make it through a Senate committee. In the years since, bills have not fared better. The Stop Child Abuse in Residential Programs for Teens Acts of 2011 and 2013 failed. The same bill was reintroduced this past February and has stalled in committee.

There are advocacy organizations trying to increase awareness of the issue. Two of the men I interviewed found one another through a group called HEAL, which aims, in the words of its coordinator Angela Smith, to “improve laws so children and families are better informed and protected from fraud and abuse.” A group called Survivors of Institutional Abuse recently held their annual conference in New York City, where alumni and parents of schools like the Roloff homes traded stories.

Anchor predictably fell into this trend, and like the other Roloff homes it was covered it two different ways by reporters. There were short, celebratory stories in local newspapers over the years about what the homes said they were doing: helping kids. At the same time, thorough investigations by skeptical journalists have produced shocking stories of abuse at Roloff-founded or Roloff-inspired homes in Louisiana, Florida, and Missouri.

But the more I read and reread my notes, the more I kept coming back to the stories like the one about boys rubbing McElwrath’s feet or the one in which Aaron was woken up in the eerie dead of night, sent to the chapel, and forced to listen to Roloff sermons. These stories do not demand a word as dramatic as “abuse.” A better description might be “unsettling.”

To some of the boys at the school, and certainly to the staff, these sorts of stories are normal and unremarkable. Just as there were men who still appear traumatized by what they witnessed and experienced, others remember a kind, peaceful environment. Feelings of where a line has been crossed — and where the law should get involved — are inconsistent, and might even change over time for a single person. Many of the boys simply accepted their experiences, but then years later as adults came to see what happened to them as wrong. Often it took finding someone else who had the same experience to validate the idea that what happened truly was wrong. If it was illegal, there is little recourse: in many cases around the country, staff at abusive residential programs have not been prosecuted due to the passing of statutes of limitations.

Still, just acknowledging what occurred can sometimes feel like its own small victory. About a decade after they left Anchor, in 2012, Sam found Michael living in Houston. They hadn’t spoken in years, but Sam drove down from his home in Dallas and they spent the day together. They found themselves coloring in each other’s sketchy memories of Anchor. “For a long time I started to believe I dreamed it,” Michael told me. Sam “showed up and said, ‘Hey, this stuff really did happen.’…He made it real.”

***

This story was produced for the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

***

Maurice Chammah is a writer and musician in Austin, Texas who studied journalism in Egypt as a Fulbright student, 2011-2012. More about him at http://www.mauricechammah.com. He writes regularly for The Revealer.