By Don Jolly

“Mr. President, I’d like to pick up this Armageddon theme,” said Marvin Kalb. Ronald Reagan shifted his weight, eyes narrowed in concentration. It was 1984, his second debate with Walter Mondale, and the Kansas City Municipal Auditorium was done up like interstellar space. Everyone — the audience, the panelists and the candidates — floated against a curtain of black.

“You’ve been quoted as saying that you do believe, deep down, that we are heading for some kind of biblical Armageddon,” continued Kalb, the chief diplomatic correspondent for NBC News. “Your Pentagon and your Secretary of Defense have plans for the United States to fight and prevail in a nuclear war. Do you feel that we are now heading perhaps, for some kind of nuclear Armageddon?”

Reagan was indignant. And confused. “Mr. Kalb,” he said, “I think what has been hailed as something I’m supposedly, as President, discussing as principle is the recall of just some philosophical discussions, with people who are interested in the same things; and that is the prophecies down through the years, the biblical prophecies of what would portend the coming of Armageddon, and so forth, and the fact that a number of theologians for the last decade or more have believed that this was true, that the prophecies are coming together that portend that. But no one knows whether Armageddon, those prophecies mean that Armageddon is a thousand years away or day after tomorrow.”

He paused, then, pivoted to the Star Wars program. The answer doesn’t make any more sense now than it did in 1984. He crushed Mondale in a landslide.

Reagan’s oblique reference to growing Armageddon speculation over the “last decade,” is perfectly in line with the expansion of a kind of Christian theology known as “dispensational premillenialism” during the 1970s. While this tradition has deep roots in “fundamentalist” culture, it exploded into the national mainstream through Hal Lindsey and Carole C. Carlson’s paperback The Late, Great Planet Earth, first published in 1970. In it, the authors argued that world events such as the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine and the development of the atom bomb served to fulfill promises made in the Bible. Reading the news, they said, proved the end was nigh.

The Late, Great Planet Earth was past its thirty-sixth printing by the time Reagan answered Kalb. It sold more than any other non-fiction book of the 1970s. Prior to its pop-cultural and political success, however, dispensational premillenialism boiled on the fringes. Before Lindsey and Reagan, there was Salem Kirban — and a book that promised to tell its readers “HOW THE WORLD WILL END.”

“When this happens,” said its cover, and “if you still remain… READ THIS BOOK.” It would be, Kirban promised, your Guide to Survival.

The practice of looking for the fulfillment of biblical prophecy in current events is an old one. Dispensational premillenialism however, is relatively young. The approach solidified in the early nineteenth century through the ministry of a frustrated ex-priest from the Church of Ireland named John Nelson Darby. Darby, through a series of lectures and writings, transformed his readings of Ezekiel, Daniel, and Revelation into a nuanced model of history. Time, he said, was divided into a series of stages, called “dispensations,” governed by God’s behavior toward mankind. For him, the present dispensation was the Church Age — a largely meaningless pause preceding the coming “Kingdom Age,” wherein Christ would return and the final victory of good over evil would be enacted. This age would begin, said Darby, with the mass disappearance of the faithful, as revealed by First Thessalonians 4:16-18:

“For the Lord Himself will descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of an archangel, and with the trumpet of God. And the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air. And thus we shall always be with the Lord. Therefore comfort one another with these words.”

He called it the Rapture. Following it, he said, would be a time of troubles, primarily discussed in Revelation. Boils. Locusts. Moons of sackcloth. Seas of blood. “Dogs and cats — living together — mass hysteria!” to quote another landmark speech from 1984.

Darby’s theology came to be known as “dispensational premillennialism” because, for him, the thousand-year period of Christ’s dominion promised in Revelation would occur without the intervention of human beings. This set him apart from the postmillennialists. For them Christ’s kingdom was the culmination of his follower’s work in the world — their salvation arrived after the millennium began. Darby imagined to inverse — salvation by Rapture, before the millennium.

By the time of Darby’s death in 1882, dispensational premillennialism was an influential theology in Europe. Across the Atlantic, and over the course of the twentieth century, it became an integral part of many Christian organizations, including the Southern Baptist Convention and various charismatic and Pentecostal churches. It appears in the rhetoric of such American religious luminaries as the Billys Sunday and Graham, Pat Robertson and, of course, Ronald Reagan — hence Kalb’s unease.

It also inspired a robust popular literature. After the Second World War and prior to 1970, premillenialist literature was a staple of specialty Christian publishers and booksellers. This is why Salem Kirban’s Guide To Survival, first published in 1968, could boast “over 1/4 million sold” on its exquisitely designed cover. The achievement has won him little enduring fame.

Today, Guide to Survival is almost forgotten, even in premillennialist circles. Its format is a kind of prophetic collage, containing Kirban’s analysis of current events and his predictions for the future, copiously illustrated in a variety of styles. His predictions, rooted as they are in the late Sixties, seem less than credible today. Few now look at the 1968 Democratic Convention as a sign of the end-times, for example. Political rearrangements have alienated Kirban from the American “fundamentalist” audience as well. His warning against the proliferation of guns in American life, for instance, seems dangerously progressive for 2014. That said, there are richer rewards in Kirban than either accuracy or political expedience.

Salem Kirban’s interest in dispensational premillenialism began around 1938, when he was a child. The author first encountered it, according to Guide to Survival, in “a little missionary Church in Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania.” There, overhearing talk of Revelation served as the “first spark that kindled [his] flaming desire … to understand God’s prophetic promises.” It would prove a lifelong practice. Beginning in the late 1960s and ending with his death in 2010, Kirban wrote over fifty books, many on premillenialist topics. By 1970, he was the head of his own independent ministry and religious publishing imprint. It was then that Lindsey and Carlson, and their competing efforts, made it big.

The success of Late, Great Planet Earth was won in large part by its “slang-filled colloquial style” and “mass-culture allusions,” argues the historian Paul Boyer. Kirban, by contrast, writes in a style that might best be described as breathlessly circuitous. An ecological passage from Guide to Survival, for example, begins by asking, “can it be that America is reaping a harvest of destruction brought about by sowing the seeds of corruption?” “The heritage that they will rapidly leave to the world is fast bringing us to Destiny Death,” he concludes — “Destiny Death” being the name of the chapter in which these words appear. This trick of concluding with titles comes up again and again in Guide to Survival. As a result, it reads something like a two hundred page movie poster. According to contemporary reviews from such outlets as NPR and the SF Weekly, Kirban’s prose is “so bad it’s good.” I don’t think so. It’s weird, certainly; a work of strange rhythm. Disentangling it, though, works to disorient the reader in a way entirely appropriate for a book about the end of time. Lindsey’s embarrassing counter-culture patois, which renders the apocalypse as “the ultimate trip,” comes off tame in comparison.

Kirban’s constant repetition of chapter titles for emphasis is part of a larger rhetorical strategy employed throughout Guide to Survival. At all points within the text, Kirban carefully reminds his readers of their position — signposting the concepts which have preceded any given section and stating, plainly what is coming next. This structure is assisted by the book’s standout feature: charts, illustrations and photographs. Take this graphic depicting the timeline of the Rapture and its succeeding tribulation:

Not only is it clear and attractive, its sense of design works to impart Kirban’s theology with a minimum of words: the Rapture portion, for example, draws the eye upward from “the grave” to a full, round space containing a relevant snippet of Thessalonians. Visually, it mimics the action it describes while privileging the biblical verse upon which Kirban’s beliefs are founded. The author’s use of red spot-coloring, too, suggests an admixture of blood and ink. Kirban employs the technique throughout Guide to Survival.

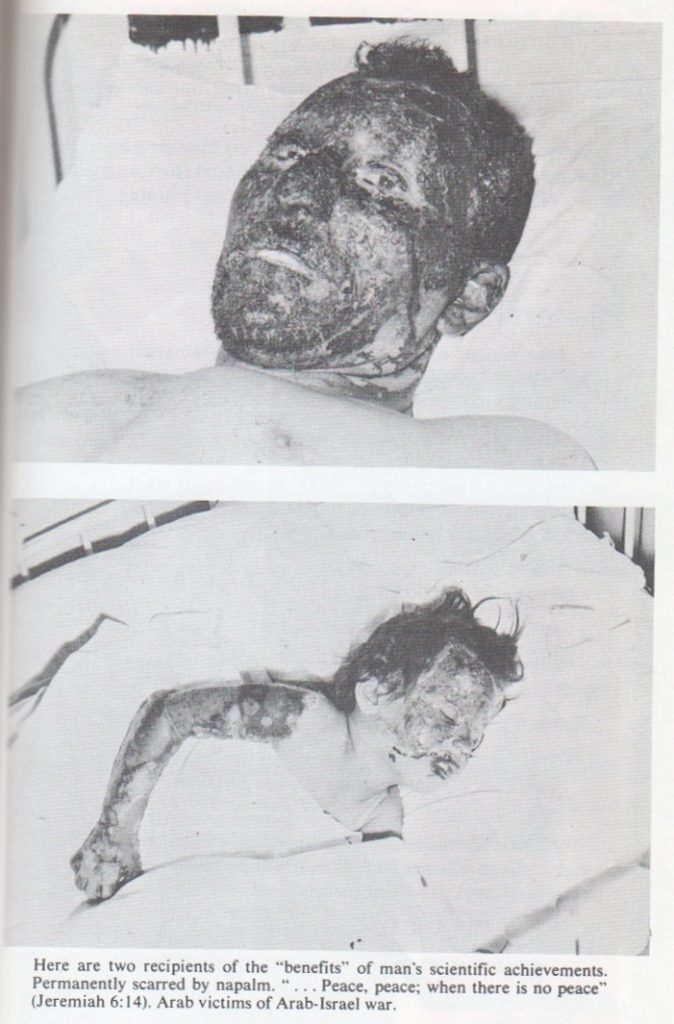

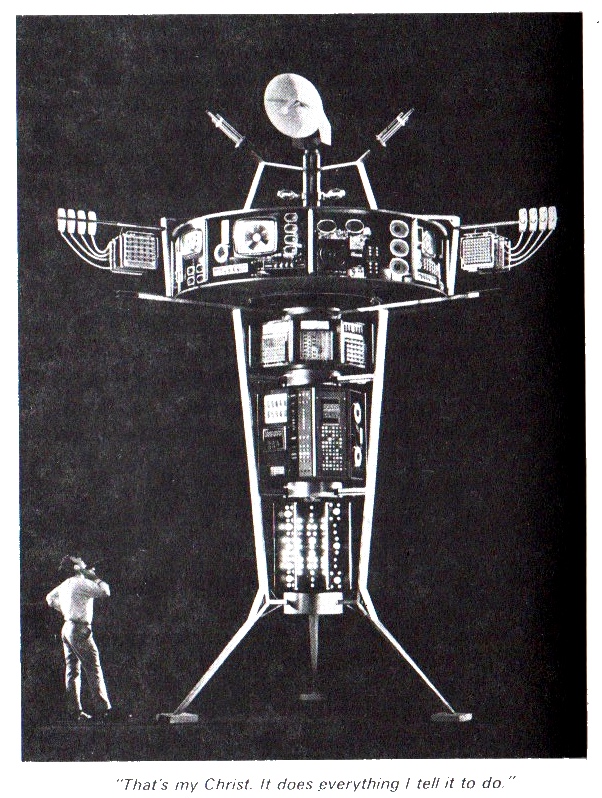

Dispensational premillenialism, since its inception, focused on orienting its adherents within history — a history that, Darby believed, had both a definitive ending and a definitive end. Thus, Rapture charts and timelines have long been a feature of premillenialist material culture. Kirban, working more than a century into the tradition, clearly means to make his contribution along accepted genre lines. Guide to Survival’s aesthetic, however, is highly idiosyncratic. In sections of the book dealing with present social ills, for instance, Kirban relies on artfully selected black and white photographs to accompany the text. Some were even taken by the author, including a haunting image of coffins piled for use on an American military base in Vietnam. Kirban pulls no punches — when Guide discusses the horrors of technological war, he fills the page with actual napalm injuries — including those inflicted on children.

As Kirban moves into the Rapture and the tribulation, his Guide relies increasingly on cartoons. Visually, it grows both more approachable and more abstract, even as the text grows darker. When describing the divine wrath of the last days, for instance, Kirban tells us that, “with the judgment of the First Vial, there comes a great running festering sore upon the body of every man who gave allegiance to the Antichrist and the False Prophet.” It’s a spare sentence, but the imagery is appropriately grotesque. The actual image accompanying the passage, however, gives the Cliffs’ Notes of the situation: “BOILS,” it says. “Malignant sores affect those with the mark of Antichrist.” Helpfully, a cartoon of a man with a 666 tattoo and a chest full of red spots appears beside this summary. In an aesthetic touch that is perfectly Kirban, he’s smiling. No other Rapture writer could be as comforting — and as unsettling.

Guide to Survival is an evangelical text in the broadest sense of the word. At its conclusion, Kirban implores his readers to “give [a] simple prayer of faith to the lord,” noting that it need be neither “beautiful” nor “oratorical.” He even offers a form, in half-page box, which the faithless are encouraged to sign and date. “If you have signed the above,” he says, “I would like to rejoice with you in your newfound faith… you are saved, and are a saint of God.” In this passage, Kirban’s odd aesthetic reveals its arc.

For Darby, the Rapture was a necessary innovation. By positing that the “Saints” would rise before the time of tribulation, the first dispensational premillenialist removed the sting from the horrors produced by a literal reading of Revelation. The tribulation, for premillenialists, may be a time of unspeakable and unknowable horror but it is also a time that can be easily escaped. This is why Kirban confronts his readers with the ugly reality of the world circa 1968, as captured on film. And this is why he illustrates the tribulation with bold, informational charts and spare caricatures. With nothing but design, he’s arguing for escape and, by the end of the book, offering it directly. As a work of visual and written art, the Guide to Survival stands out.

Since 1968, dispensational premillenialism has waxed and waned as a strand of thought in American Christianity. In charting its course, it’s tempting to focus on the premillennial presence in politics and publishing. Figures like Pat Robertson, Hal Lindsey and George W. Bush have brought the teleology of tribulation and Rapture onto our television sets and drugstore paperback stands. Neither place is where it started however. Within the massive body of dispensational premillenialists since Darby, there have been many writers, ministers and interpreters — each with some unique contribution to the field. To ignore those achievements is short sighted. Kirban, whose idiosyncratic Guide was published just before premillenialism’s latest mainstream explosion, is one premillennialist worth retrieving. To me, he seems like a great American eccentric —and, as usual with great eccentrics, a great artist too. When Ronald Reagan spoke circuitously and opaquely about the Rapture we elected him president. It’s too late to do that for Kirban — but we could at least keep his books in print.

Guide to Survival is, as I said, a collage of styles and approaches. In one of its stranger chapters, Kirban renders the moment of the Rapture through first person narrative. “It is sometimes difficult for one to imagine what will happen when the actual Rapture occurs,” he writes. “Therefor I have written the next chapter in novel form … [perhaps] it can more graphically describe to you the vivid realities of these events.”

What follows in this chapter, which Kirban titles “I Saw The Saints Rise,” is a strange admixture of science fiction, domestic drama and prophetic interpretation. It ends with a pair of pitches.

First: “While there is still time … you have one choice to make,” Kirban says. “DEATH by rejecting Christ,” or “LIFE by accepting Christ as your personal Saviour [sic]… I pray that you choose LIFE!”

Second: “I SAW THE SAINTS RISE is the first chapter of a novel entitled 666. You may secure this novel … by sending 2.95 to SALEM KIRBAN, Inc. Kent Valley Road, Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania 19006.”

I must confess that, despite my respect for Kirban, I haven’t taken him up on the former. The latter, however, worked like a charm.

Next Month:

***

“The Last Twentieth Century Book Club” is a monthly column about religious ephemera. Prior columns can be read here:

***

Don Jolly is a Texan visual artist, writer, and academic. He is currently pursuing his master’s degree in religion at NYU, with a focus on esotericism, fringe movements, and the occult. His comic strip, The Weird Observer, runs weekly in the Ampersand Review. He is also a staff writer for Obscure Sound, where he reviews pop records. Don lives alone with the Great Fear, in New York City.