By Don Jolly

In the slickly produced, “Beat It” style video for his 1993 song “The Resurrection Rap,” the once-popular Christian contemporary muscian Carman recasts the narrative of the passion as a brawl between theologically inclined street gangs. His Jesus is white, unshaven and wears a leather jacket with a blue bandana, the signifying accessory of his “crew.” At the climax of the song an all black gang, implicitly led by the Devil, beats Jesus to death with knives, chains and nun-chucks. They toss his body in a dumpster.

The media scholar Heather Hendershot, in her 2004 volume Shaking the World for Jesus, devotes several lucid chapters to the rise and transformation of Christian Contemporary Music (C.C.M.) in the latter half of the twentieth century. Naturally, she touches on Carman — as do her subjects. “I try to avoid Carman like the plague,” one unnamed professional in the Christian music industry told Hendershot. “I think he’s a heretic… His whole thing… I think it borders on prostitution of the gospel, quite frankly.”

Last month, when I reviewed Carman’s music video collection The Standard, I concluded with a throwing up of hands. Whatever message Carman was trying to transmit had been hopelessly garbled, I said, by its medium of transmission. Interestingly, Hendershot’s correspondents in C.C.M. agree with this sentiment, albeit on theological grounds. It’s tempting to end the conversation there: Carman, whatever his final intentions, simply failed to entertain or uplift. As an artist he was, at best, a clown and, at worst, a prostitute. So, why keep talking about him?

The answer is simple, and injurious to my critical vanity. Whatever my opinion of Carman’s comprehensibility, his work has certainly communicated with its intended audience on a massive scale. When “The Resurrection Rap” was released, Carman’s donation-supported stage shows were commanding national and international audiences in excess of 50,000. Over the course of his career, he’s moved ten million albums. Billboard magazine, in 1990, named him “Contemporary Christian Artist of the Year.” What’s more, C.C.M. producer Cindy Montano, in her interview with Hendershot, noted that Carman’s work ignites a religious spark in its audience. After Carman T.V. specials, Montano said, people often call into the network “seeking salvation, wanting someone to pray with them… Carman’s videos are very effective at touching people.”

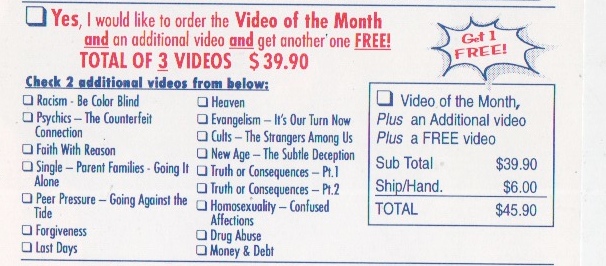

Montano was speaking of Carman’s music videos — but works such as The Standard weren’t his only releases in the VHS format. In the early 1990s, at the height of his career, the singer’s Carman began a monthly “video club,” called “Time2,” whose members received a monthly VHS dispatch featuring new music videos, tape of live C.C.M. performances, interviews on evangelical topics, ministry from Carman himself, and, as one advertisement for the series put it, “[comedy] sketches with an apparent purpose.” These tapes, running a highly-televisable thirty-minutes each, play like a gaudy, early-nineties riff on the ramshackle 1944 radio-magazine The Orson Welles Almanac, which was an attempt by Welles to merge broad comedy, serious drama and political comment into a showy half-hour capable of selling Mobil gasoline. Critics at the time were quick to point out that Welles, whatever his talents, was no Jack Benny. Carman, in turn, is no Orson Welles.

“Time2” is a mess. The comedy fails to land, the interviews play like shrill monologues and the split-second editing employed throughout makes even straightforward segments nearly incomprehensible. Where the club succeeds, however, is in the clarity of its intent. Each episode articulates a proper evangelical “response” to a relevant issue, using a variety of sequences and tones to deliver an unwavering didactic message. In so doing, I believe, the series lays bare Carman’s appeal — and the features of his work which either embarrass or inspire, depending on your point of view.

The episode “Faith with Reason,” provides a representative example. On this videotape, Carman promises to address the idea of the scientific and historical “accuracy” of the biblical text, with his position being that direct evidence — while nice — is of secondary concern. Towards this end, “Time2’s” regular “Buzz” feature is devoted to attacking the material culture of dirt-bike and dune-buggy enthusiasts, implicitly because their fanaticism is unproductively worldly. Following a performance from the C.C.M. artist Cindy Morgon, the theme is again picked up in a comedy sketch featuring two redneck caricatures sharing a porch and discussing “belief” over a deafening soundtrack of canned birdcalls. One of them “believes” only in things he can see — including wallpaper and pickles. The other, a Christian, takes these pronouncements in stride for four excruciating, mirthless minutes. In the end, afraid that its audience might miss the point, the “Time2” provides an onscreen quotation of John 20:29: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believed.”

The latter half of the tape is dominated by Carman. First, the musician flashily appears on “Time2‘s” Saturday Night Live-like main stage to interview an author of popular Christian apologetics, making sure to provide the requisite talk show plug.

An unrelated C.C.M. video follows, preceding the climactic moment when Carman takes the stage alone to minister directly to his viewers. “Don’t follow what you hear or what you see or what you experience,” he says, over a score of weeping pianos. “Follow what’s already there in God’s revelation to mankind.” Biblical quotations are helpfully presented throughout by colorful, frame-filling graphics.

As in Carman’s music videos, a series of obvious cross-pressures are at work in “Time2.” Television is probably the most visible, given the series’ focus on dividing itself into segments of three to five minutes in length, complete with simulated commercial breaks. Along with this format comes an attempt to be entertaining in a familiar, televised way — hence “Time2‘s” eclectic mix of talk show, sketch comedy and musical performance. Often this approach muddles “Time2’s” religious message, as in the segment on desert sports from “Faith with Reason.” In this sequence, loud rock music plays over scenes of leaping dirt-bikes and sand-spitting dune-buggies, glorifying the supposedly “material” world the segment is ultimately meant to attack. The world outside of evangelical culture can be fun to look at, “Time2” acknowledges, but it is also a domain of spiritual threat.

These two stances toward the non-evangelical are played out prominently in “Time2’s” choice of episode topics.

Each month, for the most part, the club devoted its time to articulating the proper evangelical “response” to a contemporary topic of religious, social or political interest. Two of the entries I managed to track down, “A New Age” and “Psychics: The Counterfeit Connection” explicitly dismiss the spiritual claims of practitioners in non-evangelical traditions.

Psychics, Carman says, exist in an area of “profound spiritual darkness,” a zone made all the more dangerous by its omnipresence in “secular” pop-culture. Throughout this episode of “Time2,” seemingly independent artifacts such as Ouija boards, psychic hotline commercials and roleplaying games are woven into a singular demonic conspiracy bent on the seduction and death of the evangelical audience.

“A New Age,” an episode that finds similar malevolence in “Star Wars,” crystal healing, the recycling movement and “relative morality,” carries a particularly paranoid message. In one sequence of interviews, a number of evangelicals describe a conspiracy to indoctrinate children in “new age” practices through public education. Johanna Michelson, a reoccurring “Time2” expert on the occult, argues vehemently that the tainting of public education is simply the first step in a secretive plot that aims to create an irreligious one-world government, necessitating a future where “Christianity will be the enemy of the superstate.” This apocalyptic pronouncement is presented without comment or counter-argument. In “Time2,” such a scenario is the logical outcome of a culture where religious doctrines have become disturbingly fluid — one sequence, late in the episode, shows a car bumper gaining and losing political stickers over the passage of time. The effect is both humorous and chilling — in “Time2’s” conception of the world, such everyday sights are evidence for the proactive reality of evil.

This paranoid stance helps explain Carman’s engagement with popular culture as a whole. While the musician assumes the aesthetics of pop, quoting from Michael Jackson and Nirvana in his music videos and aping a variety of television forms in “Time2,” this act of assumption is predicated on the necessity of divorcing such stylistic forms from whatever “secular” content they might contain. The status of this project, even among evangelicals, is by no means uncontroversial. The Revered Jimmy Swaggart, for instance, once famously argued that using the aesthetics of rock n’ roll to convey a Christian message was like “giving a drug addict methadone.” From his point of view, the format of secular popular culture was inherently corrupt. Carman, implicitly, takes the opposite position.

While “Time2” reveals that Carman views the “secular” world as deeply threatening to evangelicals, it also proposes a cultural landscape where such threat has been expunged. When Carman quotes from “Beat It” in his “Resurrection Rap” retelling of the passion, he is actively creating a world where all the aesthetic pleasure of Jackson’s product is ideologically vacated, the resulting void neatly filled with clear evangelism. There is nothing wrong, Carman seems to say, with enjoying the look and feel of non-evangelical pop — these elements, in and of themselves, are meaningless. In a world where evangelism is the only acceptable content, Carman would be the king of pop.

Carman exists, however, on our world — and within the material subculture of evangelical film and music. Hendershot, in Shaking the World for Jesus, carefully explores the nature of this space, arguing that growths in evangelical education and affluence since the mid-twentieth century have rendered it profoundly unsettled. Even as Carman doubled down on open didacticism and a healthy paranoia towards “secular” ideology in “Time2,” his contemporaries began to push more nuanced, ambiguous and conversational approaches to faith. In the field of C.C.M., for example, the most popular artists at the turn of the last century were those whose music could “cross over,” finding airtime on such “secular” venues as the cable channels M.T.V. and V.H.1. This passage necessitates a certain amount of subtlety in regards to a musician’s evangelical message — it must be present for those who know what to look for, and invisible to the larger, non-evangelical audience the artist wishes to reach. Carman is rarely subtle, and his faith in the invisible is, ironically, never invisible itself. “Time2,” and Carman’s work as a whole, deliver an openly evangelical message with a maximum of flash and expended capitol. This, Hendershot argues, makes Carman the “most evangelical in theory and the least evangelical in practice” of any contemporary Christian musician. He preaches, exclusively, to the choir.

The antipathy towards Carman expressed by Hendershot’s contacts in the C.C.M. industry makes perfect sense in this context. For them, a certain amount of submission to the aesthetics of non-evangelical pop is seen as necessary for success — maybe even hip. Carman, on the other hand, creates a world in his videos wherein pop aesthetics are made to submit themselves, totally, to evangelism.

Last month, I spoke of the science-fictional occultism of the VHS format. “Time2,” and Carman’s works as a whole, are a perfect example. They’ve fallen to earth through a tear in space-time, a portal to another universe. In their place of origin, Carman is not “the Christian Michael Jackson,” but is, instead, a wholly novel cultural force who fulfills the role of Jackson within a fundamentally altered system of culture. In this world, everything is evangelical. Evangelical pop is simply “pop.” No submissions, substitutions or alterations are required.

VHS tapes are products of a different time, the unknown of not-quite twenty years ago. Even when they were new, such tapes were artifacts — small documents, speaking out of turn, imagining a world where the dominant cultural discourses have been displaced. To those without such imperial aims, evangelicals and non-evangelicals alike, Carman will always come off tasteless. To his core audience, his “subscribers,” however, things like “Time2” must look at least a shade millennial.

***

Don Jolly is a Texan visual artist, writer, and academic. He is currently pursuing his master’s degree in religion at NYU, with a focus on esotericism, fringe movements, and the occult. His comic strip, The Weird Observer, runs weekly in the Ampersand Review. He is also a staff writer for Obscure Sound, where he reviews pop records. Don lives alone with the Great Fear, in New York City.