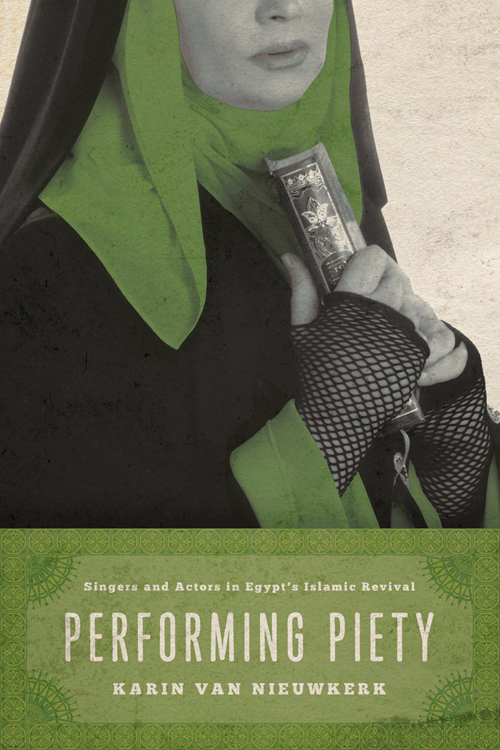

“Performing Piety: Singers and Actors in Egypt’s Islamic Revival,” by Karin van Niewkerk (University of Texas Press, 2013)

By Maurice Chammah

Mickey Rooney, Chris Tucker, Kirk Cameron, Bob Dylan, Mr. T. This list of celebrities, which you don’t see very often, represents some of the bigger names who reinvented themselves as born-again Christians. Of the group, only Cameron really left the mainstream entertainment business to star in Christian films like Left Behind and Fireproof. Many others made the transition with less fanfare. Mr. T mostly speaks at small community churches. Chris Tucker has said almost nothing publicly.

But together these celebrities show us something else. They represent a slow and broad turn towards evangelical Christianity that permeated American popular culture throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Their born-again narrative tapped into a broader cultural movement that by the 2000s had already found a place in American political life, in Jimmy Carter, the Moral Majority, and years later in George W. Bush’s oft-professed faith. Born-again politicians and born-again entertainers create a context for one another, and allow non-famous Americans to see their own decisions to join a church and have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ as part of the mainstream.

That dynamic has been easier to understand since I began exploring it in the context of Egypt, a country that also saw a huge swing towards public religiosity at the same time that Islam found a voice — albeit a constantly repressed one — in the country’s political life. The US had Jimmy Carter, who talked about being born again only to lose an election to Ronald Reagan’s merger of the far right with evangelical Christianity. Egypt had Anwar Sadat, who bolstered his image as a pious Muslim just as he crushed radical Islamists. Carter lost a second term to his co-religionists. Sadat was assassinated by his.

Danish anthropologist Karin van Nieuwkerk, explores these dynamics of religion and public life in her new book, Performing Piety. A study of celebrities who publicly renounced “sinful” lifestyles as dancers, singers, and actresses, the book looks at how they reinvented their public images as beacons of worship, preaching, and charity.

Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, Egypt underwent a social transformation in which much of the population turned to Islamic ritual in their daily lives. A small group of anthropologists, Saba Mahmood and Charles Hirschkind among them, have studied in rich detail the Islamic culture that came out of that period—mosque study groups, sermons distributed by cassette and religious television. Van Nieuwkerk’s study of celebrities who “repented” and turned their back on previously “sinful” (if highly lucrative) careers, adds to this literature.

Van Nieuwkerk argues that their self-styled narratives of finding faith are a repository for the imaginations of ordinary Egyptians, who see themselves in these stars. “Since they are famous stars,” she writes, “they themselves feel an urgent need to ‘celebritize’ piety, to hide breaches and imperfections as well as to uphold and carefully monitor their public images as pious exemplary personalities.”

And because the piety of celebrities is so embedded as a phenomenon in the intricacies of Egyptian political and cultural history, van Nieuwkerk must explain that history in long, richly detailed passages. The result is a lucid explanation of the myriad forces that have shaped contemporary Egyptian society.

Van Nieuwkerk is less of a critical theorist than others in her field. There are none of the broad challenges to canonical Western thinking that made Saba Mahmood’s The Politics of Piety a fascinating and ambitious text but wholly unapproachable to non-academics. This book is deliberately not as grand a statement, but its modest effort to provide context for a little understood historical trend make it actually far more readable to non-specialists. She begins each chapter with the story of an individual star before exploring a broader theme. In the 1980’s, that theme is the repentance and veiling of a number of female actresses and dancers. Their public narratives dovetailed with the broader movement towards piety in Egyptian society.

Then, in the 1990’s, the number of stars reached a “critical mass” that “greatly disturbed the secular field of art.” Secular newspapers, seeing in these conversions evidence of growing radicalism in their society, satirized the stars’ self-presentations, bringing even more attention to them. Since political activism was silenced and the Muslim Brotherhood was banned, popular culture and the press became a place to debate secularism and Islamism. “Gender, art, and Islam, condensed in the symbol of the veiled actresses, proved a perfect way to delineate the opposing ideals of secularists and Islamists,” van Nieuwkerk explains, “in which the religious idiom nevertheless became inescapable, strengthening the Islamization of the public sphere.”

Van Nieuwkerk keeps an eye on how her subjects were perceived by ordinary Egyptians, and she finds an ambiguity that illustrates a tense relationship between secularism and Islam. Apparently, a popular joke in 90’s Egypt went like this: “Who are the second best-paid women in Egypt? Belly dancers, of course, because Saudi tourists throw banknotes of a hundred dollars on their feet while they are dancing. Who are the best-paid women in Egypt? The converted belly dancers, of course, because Saudi sheikhs transfer banknotes of a thousand dollars to their accounts if they stop dancing.” Many secular Egyptians were distrustful of the motivations of the repentant stars, and used humor as a way of expressing their anxiety at the rising influence of Islam in their society, just as their fellow Egyptians happily embraced it.

In the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, a period van Nieuwkerk explores in the final part of the book, there was a trend towards “a relatively open view that encouraged artists to return with pious productions.” New debates arose about whether “art with a purpose,” that is, openly Islamic productions in which women always wore headscarves and were never seen in intimate situations with men, was a refreshing alternative to mainstream, secular television and film, or whether it was tasteless evangelism. She doesn’t answer the big, unanswerable questions, but she asks them. “Should we interpret the new ‘lite’ trend in Islamism as an extension of the Islamist political project by, seemingly, nonpolitical means?” she writes. “Or does it indicate a change of direction away from political activism toward consumerism and individual pursuits?”

Van Nieuwkerk’s study ends in the years before the uprisings that brought down Mubarak and the political turmoil that has lasted until now, but her book offers an important addition to our understanding of the unresolved tensions that will continue to define Egyptian society in the coming years. Mubarak, a celebrity but a profoundly alienating one, kept his foot on the Muslim Brotherhood just as he oversaw a society slowly growing more religious. Once he was gone, that society elected the Brotherhood’s candidate, Mohamed Morsi, but they tossed him out as well. One of his major faults was always said to be a lack of celebrity charisma. He was a bumbling, quiet technocrat who failed to capture the audience’s attention.

Nobody knows what kind of leader could bring Egypt together, but he (a ‘she’ is unlikely) will have to understand both how to be a celebrity and how to negotiate subtly between Islam and secularism. The stars profiled by Van Nieuwkerk in this book are unlikely to become politicians — no actor-presidents like Ronald Reagan have emerged — but they are the clearest examples thus far of such a strange balance of forces. It’s a balance anyone who tries to lead Egypt will have to embody.

Maurice Chammah is a writer and musician in Austin, Texas who studied journalism in Egypt as a Fulbright student, 2011-2012. More about him at http://www.mauricechammah.com. He writes regularly for The Revealer.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.