By Don Jolly

Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson was an author of conversion — uniquely empowered to capture the emotional and intellectual currents of a shift in religious identity. In his first novel, The Light Invisible, for example, conversion is never confined to the skull of the convert. For Benson, the strength of such a shift explodes into the outside world, manifesting sounds, sights and textures with both convincing physical embodiment and potent allegorical meaning. In The Light Invisible the immaterial takes on material form.

The book is structured as a series of vignettes, ostensibly the supernatural visions of a pious priest, each occurring in a different phase of life. In one episode, Benson’s narrator recalls shooting a bird unnecessarily, only to catch a fleeting glimpse of a bloodless face between dark branches, smiling. In another, Benson records his priest following a shock of brilliant cloth in a wood and finding, inexplicably, the rich garment God has sewn from history. Each vision is striking, poignant and powerfully sensual. Overall, the work gives off the impression of having been composed with great feeling and excitement — as, indeed, it was. The Light Invisible was written in 1903, the same year that Benson himself was accepted into the Catholic Church. This was no small step. Benson’s father, Edward White, had been the Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Anglican Church. Benson himself was ordained, by his father, in 1895. After converting, he continued to write, emerging as a prominent catholic theologian and English popular author.

Over the course of his brief career, Benson wrote ghost stories, plays, devotionals, historical novels and even speculative works which later critics, appraising them from a midcentury perspective, have labeled science fiction. Of particular note is Benson’s 1909 novel The Necromancers, a cautionary tale addressing the dangers of spiritualism. Spiritualism, it is to be recalled, is a ragtag body of practices, very much in vogue in the early twentieth century, which held that the dead were able to communicate with the living by a variety of means, most often through a “medium” — a person of exceptional spiritual sensitivity. In the same year as The Necromancers, Benson expanded the topic for the Dublin Review. According to him, many a Catholic theologian “has stated [… ]that in his opinion the enemy to be faced in the future is no longer the old materialism of twenty years ago, [but] spiritualism itself.”

Spirit phenomena, Benson believed, were a combination of deliberate fraud, demonic possession and, perhaps, the exercise of a psychic faculty as yet unmapped. Under no circumstanced were they legitimate communications from the dead. He was suspicious of trance messages, scandalized by seances and hostile towards the unconscious, or automatic, writing by which mediums claimed to give up control of their hands to visiting specters, allowing for the composition of whole manuscripts from across the veil. This was an opinion Benson later reversed. Returning to The Necromancers in 1954, he declared:

“I now wish that I had never written it. It was a distorted narrative, where the facts, as I had really known them, were given unfair treatment, and where the truth was suppressed […] With the truth before me, I had deliberately set it aside to place in its stead falsehood and misrepresentation.”

The text surrounding this quotation, Life In the World Unseen, is a kind of technical manual for the afterlife: a description of the next world’s geography, social construction, physics and culture. The system is striking in that, time and time again, it mocks the “misconceptions” of the “orthodox Church,” presumably Catholicism, while arguing for an accessible and self-directed spirit world largely in concert with the general spiritualist conception. The honorable Monsignor had, between 1903 and 1954, experienced a second conversion, perhaps even more radical than his first: he had died in 1914.

Life In The World Unseen is, ostensibly, a book written by Benson through the assistance of medium named Anthony Borgia, whose name graces both the spine and cover of the volume. Borgia, according to his preface, was a close friend of Benson’s beginning “five years before his passing into the spirit world.” This would place the time of their meeting in 1909 — the year saw print and the height of Benson’s anti-spiritualist fervor. Borgia’s biographical details are remarkably elusive, and the matter of his living acquaintance with Benson relies wholly on the medium’s report. I find it likely, however, that if Borgia knew Benson at all, the relationship was a rocky one. Borgia admits, in any case, that Benson’s death improved things considerably. “We are old friends,” Brogia wrote, “and his passing hence has not severed an early friendship; on the contrary it has increased it and provided many more opportunities of meeting than would have been possible had he remained on earth.”

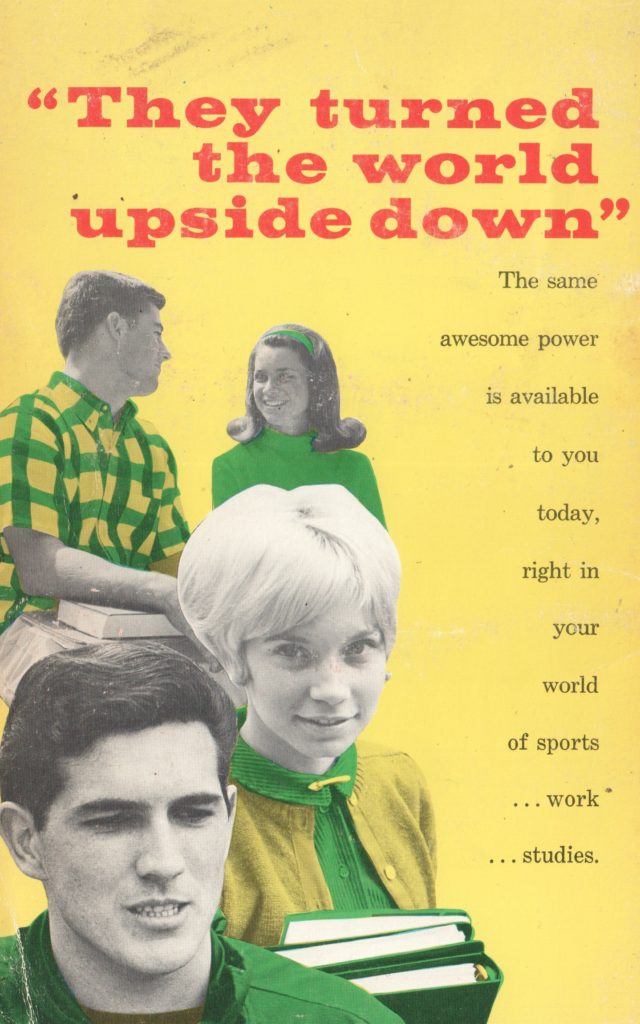

During the fifties Borgia and Benson were frequent and enthusiastic collaborators. Life In the World Unseen contains two discrete and lengthy parts: “Beyond this Life,” which recounts Benson’s death and acclimation to the spirit world and “The World Unseen,” which expands on various questions in even more detail, such as the composition of spiritual soil and the nature of ghostly music and drama. Odhams Press was the initial publisher, releasing an English edition in 1954. This was followed by a companion volume in 1956, More About Life in the World Unseen and a two-book set for the American market in 1957, courtesy of New York’s Citadel Press. This version of the work was sold by mail order, through advertisements such as this, from a 1959 issue of Fate Magazine:

As a religious document, Life in the World Unseen is fascinating. Benson, speaking through Borgia, lays out a spirit world which is, he contends, purely the product of individual spirits’ conceptions of themselves. Those who are significantly “advanced” through good works and right attitudes on Earth find themselves in a sphere of infinite delight, complete with genteel English country houses, thought-directed boats and music which manifests an automatic and preternatural light — like Laser Floyd. The less accomplished, such as “those whose earthly lives have been spiritually hideous though outwardly sublime; whose religious profession [was] designated by a Roman collar,” find themselves trapped in lower spheres, forced to live out their errors in bodies literally deformed by self pity. The bottom line is, according to Benson, “Whatsoever a man soweth […] so shall he reap.” No ghostly condition, however, is permanent — even the most abject monstrosity may be educated and advanced to the highest level of spiritual achievement. One’s earthly life, and death, simply define the place where this work begins.

Thought, we are repeatedly told, is the driving force of the spirit realm, responsible for the torments of the damned and the triumphs of the enlightened. That said, Borgia’s world is a remarkably physical one — spirits are “incarnate” in that they continue to have bodies, and a great deal of time is devoted to the description of the various material advantages and institutions supplied them. Benson’s home after death, the subject of much discussion in “Beyond This Life,” provides a representative example:

“The furniture it contained consisted largely of that which I had provided for the earthly original, not because it was particularly beautiful, but because I had found it useful and comfortable, and adequately suited to my few requirements. Most of the small articles of adornment were to be seen displayed in their customary places, and altogether the whole house presented the unmistakable appearance of occupancy. I had truly ‘come home.’”

The idea of a “home in heaven” is a common one in Christian discourse, but what marks Life in the World Unseen is the utter lack of transcendence in the concept. Benson’s “home” after death is, for the most part, just as it was in life — it’s still a house, still stocked with the same furniture and curios, still possessing of the “unmistakable appearance of occupancy.” There are little improvements, of course: no kitchen, for spirits never feel hunger, no drafts, no chills, no lack of “fresh air.” The garden is considerably improved. In total, though, there is no improvement in Benson’s lodging after death that could not be approximated by an increase in his affluence while living. His reward for a good life is, in slightly garbled form, just a well-appointed mansion with a full service staff: the dead may not eat, but the rich do not cook. Neither one sees the inside of a kitchen.

A similar circumstance is visited on the damned. During a visit to an abode in a lower sphere, Benson describes conditions thus:

“We found ourselves in the poorest sort of apology for a house. There was little furniture, and that for the meanest, and at first sight of earthly eyes one would have said that poverty reigned here, and one would have felt natural sympathy and the the urge to offer what help one could. But to our spirit eyes the poverty was of the soul, the meanness of the spirit…”

The model throughout Life in the World Unseen is to take the economic advantages and disadvantages of the living and redistribute them among the dead according to a perfect meritocracy of spirit. Even the “powers” Borgia ascribes to the unearthly body — such as communication at vast distances, instantaneous travel and access to diverse entertainments — are equivalent to the rapid technological advances of the twentieth century, the zeitgeist of rails, radios and airplanes which H.G. Wells termed “the abolition of distance” in 1928.

Life in the World Unseen went through many reprints in the 1950s, and is available in multiple editions today, many of them online. An argument could be made, that the enduring popularity of Borgia’s work can be derived from the accessibly material nature of its system, the assurance that death serves as the confirmation and extension of the economic realities of twentieth century Western life. The essential facts of the thing are still overabundance and privation. All that changes is the method by which such pains and pleasures are bestowed. Every soul has the capacity to improve their lot, according to Borgia. Hard work and study guarantee and increase in ones’ immaterial estate, the trade of damned poverty for exalted wealth. The result is a moral capitalism — a gospel of Horatio Alger. In a way, it even reflects the materialized miracles of Bensons first conversion text, 1903’s The Light Invisible. Where the earlier work was sensual and brief, however, Life in the World Unseen is extensive, shallow and gushing. His second conversion seems to have transformed Benson from a poet to a writer of catalogs.

Or, perhaps, all that changed with Benson’s death was his ability to speak for himself. It is not unusual for spiritualists to receive apologetic messages from one-time opponents of the practice (Harry Houdini has a long career in this regard), but what sets Life in the World Unseen apart is the length and nature of Benson’s protestations. The Catholic Church, to which Benson was so explosively attracted, is never named by the text. The word “catholic” never appears at all. Instead, Borgia’s Benson laments his association with “the orthodox church,” and finds it easy and uncomplicated to view it with flippant disdain. Benson’s work on spiritualism, which also passes unnamed, is a thorn in the author’s paw — his determination to “make up” for the embarrassment of its writing conditions Benson’s return in the first place. There are, we are told, still spirits practicing their earthly religion in the realm of the dead, operating under the same delusions which impacted them in life. Benson, speaking through Borgia, feels a sad compassion for such souls, and expresses no temptation to join them. As Benson was, in life, an accomplished Catholic theologian and a supernumerary private chamberlain to Pope Pius X, such details give Borgia’s work the appearance of cynicism. It’s a complicated cynicism, however, and one bound up in the tensions between materiality and immateriality which always swirled around Benson.

In 1903, Benson used material imagery to depict the Catholic faith as irresistibly real. Life In The World Unseen follows this logic only halfway, using the material as an end in and of itself rather than a rhetorical tool. For proof, just refer to the advertising and the packaging of the book. Its attractive presentation and branding as a “de luxe edition” seem clearly intended to confer a certain authority and reliability to the text. The theme follows into the content of the work, where the extension of Western material reality into the afterlife is presented as a comforting, common-sense solution to mortality’s angst. Finally, and most disturbingly, the material comes between Benson and Borgia, where the views of the dead author can be read as violently hemorrhaged by his still-living collaborator. The work defeats itself, in a way — whereas Benson’s materialization of his Catholic conversion serves to cleverly map and unnamable transcendence, the many-tiered materialism of Life In The World Unseen makes the work appear shallow and self-interested. On Earth, Benson was intrigued by glimpses of a world beyond. In that world beyond, he’s mostly interested in the quality of his furniture.

What’s interesting is that now, with the text presumably out of copyright and the private dramas of Robert Hugh Benson’s attack of spiritualism forgotten, The World Unseen has found a new life — or afterlife — on the internet. Go ahead and google it — there’s plenty of versions and a lot of discussion on various message boards. There’s a chance, I think, for this digital version of Life in the World Unseen to achieve an importance in the lives of readers far beyond its initial printing. In the half-century since Borgia’s initial publication, capitalism has only become more hegemonic, more “natural,” more “common sense.” Spiritual capitalism makes more sense now than ever — and shorn of its two other materialities, Life in the World Unseen stands ready to argue for such a system. Life is a job, death is a shopping spree.

As Benson says, through Borgia: “Religion is not responsible for all mistaken ideas!” Just don’t tell Max Weber.

NEXT TIME: