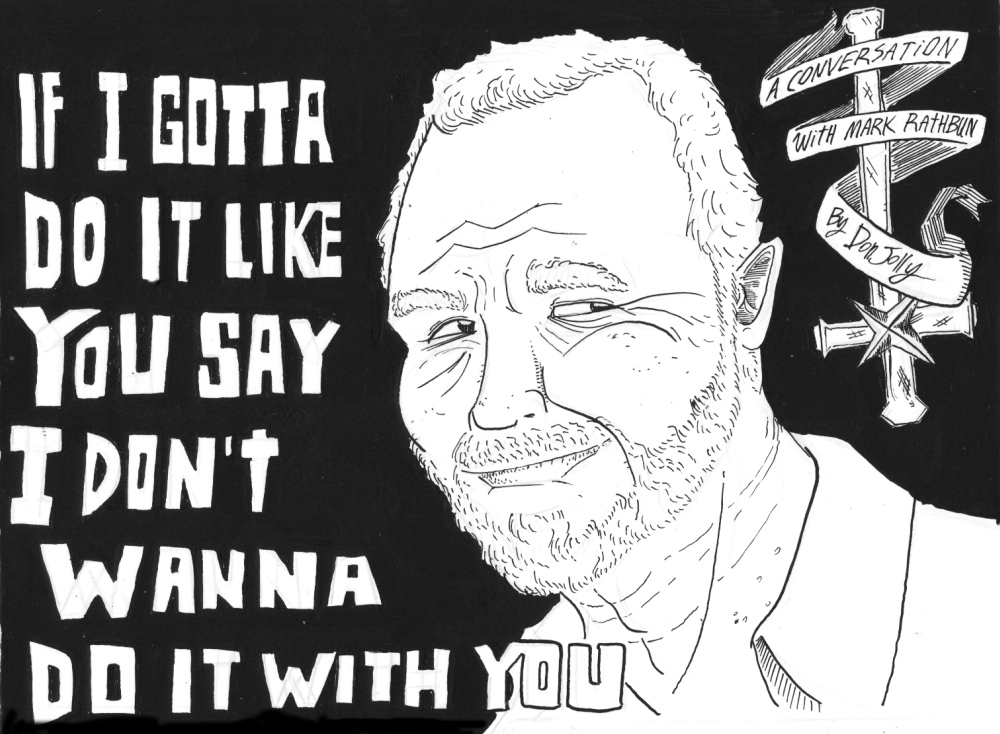

The Bridge Beyond the Bridge: Mark Rathbun’s Search for the Future of Scientology

By Don Jolly

The Phoenix Saloon is about what I expected from New Braunfels, Texas: part hustle, part heritage, an Old West paean in what used to be the frontier’s most civilized town. The Phoenix is a tall place, wood-on-wood decor and unlit except for the dusty shafts of sunlight spilling through the front windows. I arrived there on a hot June day just before noon and took a table beneath taxidermy.

Mark “Marty” Rathbun arrived a few minutes late, moving quickly, never breaking eye contact. “I know you’re a spy,” he said, sitting down. Rathbun is around fifty, bottom heavy, with sun-baked skin and hair as white as tooth enamel. “I know everything I say here is going to go right back to David Miscavige,” he said, referring to the current leader of The Church of Scientology. “So who cares? What can he do to me? What can you do to me?” His chair scraped the wooden floor as he saddled up to the table. I’d come to get a lesson on the state of Scientology from it’s most vocal outlaw.

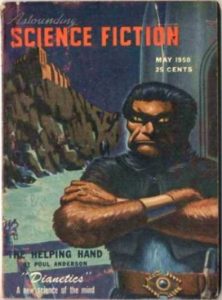

Scientology got its start in the May 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine. In those coarse pages–just behind Poul Anderson’s novelette on the vagaries of interplanetary aid, “The Helping Hand”–fiction writer and ex-naval officer L. Ron Hubbard debuted his system of Dianetics, a “modern science of mental health” that promised to open its readers to the “vast and hitherto unknown realm half an inch back of [their] foreheads.” Primarily, this opening was to be accomplished through a practice of one-on-one therapeutic interview known as “auditing.” For some, at least, it delivered. An expanded version of Dianetics released that year hovered on the New York Times’ bestseller list a straight twenty-eight weeks and early adherents experienced more than just emotional breakthroughs: there were reports of past lives returning, spirits separating from bodies. “We’re treating present time beingness, psychotherapy treats past and the brain,” Hubbard realized, writing to one of his executives, Helen O’Brien, in 1953. “And brother, that’s religion, not mental science.” By 1954, branches of the Church of Scientology had been opened in California and Washington, D.C. It was the beginning of sixty years of suspicion, counterintelligence and crime.

Scientology has never rested comfortably within the available categories of twentieth century social movements. It makes spiritual claims, of course, such as its foundational doctrine that human beings are, in reality, immortal spirits, known as thetans. It makes medical claims, too: boasting the ability to cleanse its participants of neuroses and ailments. Structurally, the Church follows the model of a diversified corporation, with organizations, or orgs, devoted to media production and the maintenance of copyright, in addition to more traditional ecclesiastic functions. The writings of Hubbard, classified as “source” within the Church, are considered both holistically consistent and completely infallible. Secrecy governs their dissemination, and members are expected to take everything in the proper order, as dictated by Hubbard’s “Bridge to Total Freedom,” a syllabus of coursework and ritual designed to move its adherents towards complete mastery of themselves and the universe. Advancing along the Bridge costs money — and that, according to most critics, costs Scientology any chance of religious legitimacy. A 1991 Time magazine cover story declared the group “the cult of greed,” dismissing its administrators as frauds and its members as victims of mind control.

In 2011, an investigation by the Village Voice estimated that, despite the organization’s grander claims, only 40,000 Scientologists were active worldwide and that the number was falling sharply. Today, once-secret Scientology doctrines, the higher levels of the Bridge, are being disseminated online and picked apart by anti-Scientology activists. Books exposing malfeasance within the Church, both by outsiders and ex-members, are more popular than ever: Going Clear, 2013‘s seminal investigation by journalist Lawrence Wright, debuted on the bestseller list where, sixty three years before, Dianetics reigned supreme. Wright’s first printing, totaling 150,000 copies, could have supplied every practicing Scientologist four times over. “Exposing” Hubbard and his followers is, in other words, big business — bigger business, perhaps, than the movement being exposed.

Today, the Church of Scientology is beset on all sides, and its enemies are substantial: news outlets, publishing houses, national governments. The loudest and brashest of Scientology’s naysayers is Mark “Marty” Rathbun. “There’s no bigger threat to the existence of the Church of Scientology than Marty Rathbun’s blog,” wrote Tony Ortega, the Village Voice’s former editor and current Scientology blogger. The Church has its own perspective, most recently articulated in the documentary Marty Rathbun: Violent Psychopath, Cult Militia Leader.

+++

Rathbun impressed me in New Braunfels. His body language embodied a particularly Texan confidence: I’m only this relaxed, it said, because I’m absolutely certain I can take you. I grew up in Texas. The dynamic at that table was a familiar one. Rathbun played benevolent predator and I, his moonstruck prey. The effect was compounded by his eyes: never blinking, clear as quartz crystal. He’d learned the technique in Portland, Oregon, 1976. It was the year he became a Scientologist.

Rathbun joined the Church while he was assisting his brother Bruce through a period of catatonia and institutionalization. “Insanity runs deep in my family,” Rathbun writes in his self-published autobiography, Memoirs of a Scientology Warrior. When he was five, his mother jumped from the Golden Gate Bridge, putting a taint on his family that most of them never got clear of. “Scott, two years my elder, has been institutionalized for ‘schizophrenia’ most of his adult life,” Rathbun writes. “Bruce, four years older than I, was locked up in mental institutions several times, and finally was stabbed to death after a barroom brawl.”

It was in hopes of helping his brother that Rathbun enlisted in Scientology’s elite administrative corps, the Sea Org, in 1978. Originally, this group operated from Hubbard’s fleet of globe-trotting yachts. By the time Rathbun joined, however, it was primarily terrestrial. The crisp naval uniforms remained.

Sea Org members are the most dedicated of Scientology’s practitioners: they live in constantly shifting “berths,” often little more than bunks, and move around the world according to the needs of the Church. Their media consumption, free time and family life are subject to strict control. In return, members are given free access to costly training. The center of a Sea Org member’s life is their advancement up Hubbard’s Bridge — not just within this lifetime, but within a succession of lifetimes. Enrollment comes with an unbreakable contract, promising service for a billion years.

The concept of an immortal thetan moving from body to body across geologic time appealed to Rathbun, according to Warrior. He saw Hubbard’s system as a powerful counter to the “genetic theory of mental health,” which held that human beings are “simply organisms, unthinkingly carrying on the […] cellular commands [they] are born with.” Scientology offered him a chance to retain his agency, even in the face of his family history. Through the teachings of Hubbard, Rathbun writes, “each of us is capable of sanity and becoming the captain of his own destiny, irrespective of genetic or biological make-up.”

This doctrine, Rathbun believes, has been denied by what he calls “corporate Scientology.” This is his term for the Church as it has existed since L. Ron Hubbard’s death in 1986. Since that time, Church leadership has passed to David Miscavige, a Sea Org member who once served as one of Hubbard’s personal assistants. Miscavige has been accused of physical and emotional abuse by numerous subordinates. The 2009 Tampa Bay Times expose “The Truth Rundown,” for which Rathbun was a critical source, provides a surreal list of examples.

It was tensions with Miscavige, Rathbun says, that led to his departure from the Church of Scientology in 2004. After escaping from a secure Church facility in California known as “The Hole,” Rathbun went off the radar, relocating to Texas to avoid the pursuit and antagonism regularly visited on ex-Scientologists, especially those departing the Sea Org. Rathbun re-emerged in 2009 as a proponent of “Independent” Scientology: a Scientological heresy, practiced without official sanction. In Independent Scientology, Miscavige’s authority is not recognized — nor is the exclusive provenance of his Church to teach the Bridge or sanction auditors. Most Independents are Scientologists who, like Rathbun, left the Church for personal reasons but still find value in the teachings of Hubbard. They deal mainly with one another: congregating online, offering courses and living the best they can, absent a settled ecclesiastical structure. Rathbun has the highest public profile of any Independent. His blog, “Moving on Up a Little Higher,” is popular with both Scientologists and anti-Scientologists alike and has netted him media coverage from The Independent, the BBC and the New York Times. In addition, he has penned three self-published books over the last two years: What is Wrong with Scientology? and The Scientology Reformation in 2012, Memoirs of a Scientology Warrior in June of 2013.

When I sat down with Mark Rathbun at the Phoenix, it was to discuss The Scientology Reformation, a volume written with those Scientologists still inside the Church in mind. In it, Rathbun carefully makes the case that the state of the Church of Scientology today is eerily similar to the state of the Catholic Church at the time of the Reformation, right down to the alignment of certain personalities. For instance, according to Rathbun, David Miscavige, is analogous to Leo X, the Pope whose material and architectural excesses inspired believers to rise up against the Church. Rathbun acknowledges that, in some ways, the equivalence is strained. “As sick and degraded and as much of a disgrace to all the world’s Christians as Leo X was,” Rathbun writes, “David Miscavige does far greater disservice to Scientologists today.” Leo X was, after all, “a typical example of medieval tyranny. David Miscavige has no such excuse.”

The Church of Scientology, Reformation contends, has become so corrupt and so focused on material gain that the spiritual advances present in Hubbard’s writings have been obscured. Independent Scientology, however, is an avenue for Scientologists to return to Hubbard’s philosophy and reclaim agency in its application and interpretation. “The [Protestant] reformation began with the recognition that no man or institution held a monopoly on the Bible and its teachings,” Rathbun writes. Hubbard’s work is similarly free.

The food arrived on brown plates, clattering as they landed. I was the only one drinking. “That chili burning your head off?” Rathbun asked. “I’m a spice guy — and this is mild. But it’s hot to me!” It was bizarre to hear Rathbun’s thoughts on chili. Reformation, I thought, had the potential to be a truly transformative work, a path by which Scientology might emerge from scandal and gain a degree of public legitimacy for its practitioners. It was focused, serious — important. If Miscavige is Leo X, it follows that Rathbun, by exposing him, is some kind of Martin Luther. I had come expecting historical austerity. What I found, instead, was human. Rathbun was less interested in discussing Reformation than I was. He encouraged me to read Memoirs, which had been published the previous week. You kinda gotta get up to speed,” he said. “When I wrote [Reformation] I was very hopeful, now I’m becoming more cynical. Maybe I’m having an influence and there’s sort of a lag on it.” He shrugged. For the most part, Scientologists within the Church seemed unwilling to hear him out. “I’m not getting immediate results so I’m getting frustrated,” he said. In addition, his picture of the Independents was more complicated than Reformation made them seem:

I’ve sort of gone full circle, to the point were the things that I find difficult about Scientology, I see them repeating [with the independents]. So I spent time looking into ‘what are those elements’ and those elements are not David Miscavige. Those elements are Scientology.

Even within Hubbard, Rathbun had begun to detect serious, fundamental flaws. Our conversation dwelled on this topic, teasing out Rathbun’s complicated engagement with his former faith. Scientology, he thought, was a valuable phase of his spiritual development. It was, however, limited. As the immortal thetan moves from body to body, Rathbun saw himself as “graduating,” carrying Hubbard’s valuable technology into a new and necessary phase. He encouraged constant evolution: a bridge beyond the Bridge.

+++

One of Mark Rathbun’s first assignments, after joining the Sea Org, was playing bodyguard for a high-ranking Scientologist who was afraid of her unhinged ex-husband. When the ex arrived with a gun, Rathbun dove for it. He ended up with the barrel pressed to his temple. In Warrior, he recalls what happened next:

CLICK! My entire body went limp and instantly I was watching the scene from ten feet above our bodies. I was sure I was dead.

He was not dead. The gun had misfired. Still, Rathbun was deeply affected by the moment, and not in the way one might imagine. “My final thought gave me a measure of peace,” he writes.

It was the recognition that, at a moment when I faced death very directly indeed, I had most definitely departed from my body. It was a clear break between the material and the spiritual.

Such moments of transcendence are central to Rathbun’s conception of religion. His autobiography is structured around them, and the various environments which have, over the years, prompted him to “go exterior.” First it was basketball and other team sports. He worked, he excelled, he departed. Then, for 28 years, the Church of Scientology. After demonstrating his willingness to take a bullet for the cause in 1978, Rathbun was taken to the secure California facility where L. Ron Hubbard was sequestered, trying to avoid prosecution. The move signaled Rathbun’s entrance into Scientology’s inner circle.

Until his departure, in 2004, Rathbun was deeply involved in some of the most sensitive operations undertaken by the Church. In the early eighties, he ran the “All Clear” unit, coordinating lawyers across the country to handle the dozens of lawsuits targeting Hubbard. In 1993, alongside David Miscavige, he was instrumental in securing the Church’s religious tax-exemption from the IRS. His one-time prominence in the Church is, in fact, central to the potency of his critiques. “Church members are trained very well to ignore anything critical that shows up in the press,” journalist Tony Ortega told the BBC in their recent documentary on Rathbun, Scientologists At War. “When Marty writes something critical of Miscavige or the Church on his blog, it reaches deep into the membership of Scientology.” For Scientologists within the Church, Rathbun’s predictions are dire.

As the sunlight shifted around the Phoenix and glasses clattered at the bar, he told me how dire. “Scientology, as a body, it’s not going to survive the age of information,” he said, speaking with certainty. “All that’s gonna survive are the ideas of Hubbard.”

Rathbun believes the Church has reached the limit of its “expansion formula,” leaving nothing but a future of decline. During Hubbard’s tenure the Church survived by releasing periodic discoveries and technology, new steps along the Bridge. “Hubbard was a master marketing guy,” Rathbun said. “He had a knack for coming up with things that people find useful in the mind and the spirit [too, but] he was a master marketer and he kept people on the edge of their seat waiting for the next development.” When Hubbard died in 1986 the engine of production ceased and David Miscavige was left with no method by which to restart it.

Since Hubbard’s death, various officials within the Church have implied–or outright stated-that as-yet unreleased levels for the Bridge exist in Hubbard’s notes and documents. “All this talk about new levels is bullshit,” Rathbun said. “There [are] none. And [Miscavige is] powerless to create them.” The final level Rathbun attributes to Hubbard was released in 1988. “The statistics have been going down ever since,” he said, referring to the number of Scientology members, “twenty-three straight years.” Through sheer attrition, he believes, the Church is finished. The situation has even given him a certain sympathy for Miscavige. “He was put into an unenviable position,” Rathbun said, reflectively. “You could’ve been mother Teresa and you still would have been up shit creek without a paddle.”

The loss of this “expansion formula” might not pose so deep a threat if Hubbard was not read within the Church as internally consistent and unquestionably correct. “With Hubbard it’s almost like stream of consciousness,” Rathbun said. “There’s all these gems within [his work] but to say nobody can change a single thing….” He shrugged, screwing up his face.

Rathbun still offers auditing to interested parties. It’s how he makes his living, partially. He still uses technologies of focus and meditation which he learned while in the Church. But these practices are isolated elements of a system that, as a whole, he finds crippled by twin strands of aggression and paranoia. The uncritical reverence demanded by Scientology towards Hubbard, Rathbun believes, serves to highlight these problematic aspects.

Talk of these aspects left Rathbun visibly agitated. He shook his head, moving quickly from one emotion to another. “One thing that I’ve wanted to do — I’m not going to do it, or maybe I will one day,” he began. “I wanna say look man, I know what the whole bridge is, okay, I’ve delivered it. The end phenomena, if you wanna take Scientology literally, the state you’re going to attain? Here it is: The videotape of Tom Cruise in that interview.”

No, not the video where Cruise is jumping on Oprah’s couch. Rathbun means the other one: a leaked video depicting cat-eyed, raving Cruise regurgitating Scientology jargon over a Mission Impossible bass line. “That is the end product,” Rathbun declared:

And these Independent Scientologists say ‘no, that’s not Scientology.’ I’ve got news for you: it is. If you follow it to the T as prescribed by Hubbard that’s the end product. I’d also like to put an asterisk in there — you’re gonna wind up like this but you’re probably not going to be famous and you’re definitely not gonna have a lot of money.

He slammed his fist on the table, almost toppling the ketchup. “There are a lot of great ideas in Hubbard,” he said. “But this package, the Scientology package… It’s hardwired to create conflict.” The proper response, he believes, is to “graduate.” Take what’s valuable, leave the rest and strike out for transcendence.

“I’m not telling people to eschew it,” he clarified. “I’m saying move on. There are other, higher levels of spiritual awareness and states you can go to.” Scientology, however, “plateaus” within the work of L. Ron Hubbard.

Rathbun has been expanding his horizons, reading voluminously and sussing out Hubbard’s potential influences and interlocutors, a controversial practice even among Independents, many of whom still believe the founder is peerless. Our discussion contained long digressions on Ken Wilbur, the American philosopher who founded Integral Theory (also known as the “theory of everything”), and the psychologist Carl Rogers. Rogerian psychotherapy is especially appealing to Rathbun because of its similarity to the practice of auditing. In some ways, he thinks, it is even superior — where Hubbard requires membership of his subjects, Rogers requires nothing. With Rogers, “it’s unconditional acceptance, it’s unconditional forgiveness, it’s unconditional safety. [Membership] taints that process, which is the most powerful process in Scientology.”

Scientology has moved from being the essential frame of Rathbun’s religious inquiries to one of many elements he feels free to explore, accept, modify and combine.

The next day on his blog Rathbun struck out again toward transcendence by publicly denying the label of “Scientologist,” Independent or not. “I do not go by any labels and I am not a member of, nor am I affiliated with, any groups,” he wrote. It was a brave move for man who has become the public face of Independent Scientology. By the time we sat down together at the Phoenix in Texas, Rathbun had already resolved to do it — he just hadn’t yet pulled the trigger. “I don’t know where it’s gonna go,” he said, shaking his head. “I told my wife, I might be out hustling real estate by the end of the year.” If the doing so shook him, he gave no sign.

Rathbun’s violent split with the Church, and now Independents, have allowed him to exercise what Marion Goldman identifies as “religious privilege” in her 2012 study of California’s Esalen community, The American Soul Rush. This kind of radical agency also echoes Catherine Albanese’s analysis of American metaphyisicals, a wide category of practitioners for whom openness to obscurity and democratic acceptance of various traditions are foundational. In this context, Rathbun exists in a storied lineage of American seekers, including Joseph Smith, Ralph Waldo Emerson and, in my opinion, L. Ron Hubbard.

+++

I drained the last of my beer. “The people I’ve audited to clear,” Rathbun said, referring to people outside the Church, “None of them really consider Scientology a religion. I don’t think any of them really considers themselves a Scientologist.” He paused, letting the lack of definition land.

“Does it matter?” I asked.

“To me it doesn’t!” Rathbun said. “But I’m just telling you. We could do an experiment. Let me put it on my blog tomorrow. Watch the response: You’re not an American?! It’ll be like that. You’ve renounced your citizenship? You commie, fundamentalist Muslim pig! It’s an identity, you adopt an identity. And the whole thing [in life] is to discover your true identity.”

There was some push back on his blog after he renounced the Scientology label, but the preponderance of comments were supportive. Since I met with Rathbun in June, his work on the blog has shifted from criticizing Scientology to assisting its readers in their graduation. “The vast majority of people who devoted time to Scientology ultimately go through the graduation process,” Rathbun wrote on August 9. It involves “reconciling what they learned and gained, differentiating it from the entrapment mechanisms involved, and finding ways to evolve and transcend as a person.”

He spoke with defiance, but one tempered by sincerity and commitment to continuing the search. “I can do all these great things with you using what I know of Scientology,” he said. “But y’know when I do it per the book, literally, like you said I gotta do it, I don’t want to do it to you.”

Scientology “is a striking example of the complex, shifting and contested nature of religion in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries,” observed scholar Hugh Urban in his 2011 book, The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion. Rathbun exists in the center of this shifting debate; perhaps he even drives it. While academics and people outside the Church may conceive of the changes within The Church of Scientology in abstract terms, Rathbun has no such luxury. Whether we recognize its legitimacy or not, Scientology is a vital and difficult cornerstone of Rathbun and his follower’s cosmography.

Rathbun left first. I followed, a few minutes later. Over the course of the meal, I had been debating something: an arrangement of shadows on his shirt. It might have been a bulge beneath the right arm — but, then again, the room was dark. I thought he might have had a gun. Maybe I was just paranoid.

It was Texas, either way.

Don Jolly is a Texan visual artist, writer, and academic. He is currently pursuing his master’s degree in religion at NYU, with a focus on esotericism, fringe movements, and the occult. His comic strip, The Weird Observer, runs weekly in the Ampersand Review. He is also a staff writer for Obscure Sound, where he reviews pop records. Don lives alone with the Great Fear, in New York City.