By Saba Imtiaz

The notion of falling in love can seem unimaginable in Jhang. This district of the Punjab province is now most commonly known as the birthplace of the virulently anti-Shi’ite group, the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), and its militant offshoot, the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi. Jhang is surrounded by persecution: on the route to Jhang is the city of Gojra, where a Christian settlement was burnt in 2009 over false blasphemy charges. In Rabwah, another city 90 kilometers away, Ahmadi Muslims have borne the brunt of a state-enforced excommunication for decades.

In the main city of Jhang, mentions of love and servitude are largely restricted to impassioned declarations of loyalty to the Sipah-e-Sahaba’s founders or the Shi’ite landlords of the district. Jhang is also the hometown of Pakistan’s only Nobel Laureate, the late Dr Abdus Salam, but his name is shrouded in obscurity because he was an Ahmadi. Jhang is heavily contested by politicians and wealthy businessmen, all jostling for space on the electoral landscape.

But on the outskirts of Jhang, love and desire burn at the grave of Heer, the original source of Jhang’s infamy.

Two women — Heer and Sahibaan — were born here. Both are stars of epic romances that have shaped folklore on the Indian subcontinent for several hundred years. These romances include the sagas of Sassui Pannu, Sohni Mahiwal and Umar Marvi, featuring headstrong, defiant characters and their doomed romances. On a surface level, these romances – such as that of Heer and Ranjha – tell a very simple story: a girl falls in love with a boy, their families disapprove, the couple pine for each other and eventually elope, only to be defeated by the enemies of their love.

While the origins of the sagas are rooted in fact, hundreds of years of storytelling – including poetry, films and songs – have transformed them into the versions heard today in their hometowns. Despite their iconic status, Heer and, to a lesser extent, Sahibaan are still symbols of shame for their families in Jhang. The notion may seem incredulous given that hundreds of years have passed since Heer died, and that the account of her life is laced with fiction, but Heer represents more than just a heroine of a tragic romance. Heer is the icon in Punjab: a symbol of a woman rising above class and clerics. Heer exemplifies the struggle of a woman’s right to choose. It isn’t just about her fight but also how she does it: by first attempting to work with and then subverting and defying the patriarchal institutions that dominated society then, and now.

In a region where history seeps from the river banks and imposing Mughal architecture, why has the memory of these women survived and what makes them relevant today? Why are they still the target of the patriarchal system that sought to defeat them?

Heer belonged to a sub-clan of the Sial tribe of the prosperous region of Jhang; the only daughter of a rich, landowning family, a legendary beauty and a prized match for any son of Punjab’s upper-class families. Ranjha was a charismatic young man from a landowning family in Takht Hazara, a skilled flutist and a Pied Piper figure who attracted women.

The complexity of their relationship, and its link to Pakistani society today, is best told through the verses of Punjabi poet Waris Shah. Shah’s fictional retelling of this saga subtly highlights the issues at stake in an agrarian and patriarchal society and the conflicts that continue to impact the lives of men and women across Pakistan. Heer and Ranjha’s saga is not just a tale of doomed lovers. It is, at its core, a story of defiance, and of will, of standing up to influential figures at home and in society.

“Heer Ranjha is essentially the most representative story of the agrarian culture in Punjab in the last five thousand years,” writer and poet Mushtaq Soofi told The Revealer. “This story has everything which was in our older society: human and familial relations, the relations between men and women and the class conflict.”

To explain the significance of Heer Ranjha to Pakistani society, Soofi notes that the epic poem starts with a simple enough issue, but one that still resonates through households across Punjab. Ranjha’s father has died, leaving land to his sons. But his brothers connive to cheat Ranjha of his inheritance.

This conflict then sets the stage for Ranjha’s life, one that gives his character more nuance than the black and white of ‘poor boy falls in love with a rich girl’.

“The brothers then bribe a judge to divide up the property in their favor, leaving Ranjha with a small piece of barren land,” Soofi explains, using the context of Waris Shah’s verses. “This is where the state gets involved, because the judge has provided a legal cover to their land grabbing, a problem we still have in Lahore and Karachi. So the family and the state institutions work together against Ranjha.”

Ranjha decides to leave Takht Hazara. Penniless, he has no choice but to seek lodging at a mosque, as was customary at the time. But the cleric of the mosque objects to Ranjha’s long hair and facial hair, saying he is only liable to be lashed. And so those other great institutions of the land – the mosque and the cleric – turn against Ranjha. He goes to the river to reach Jhang, but the boatman won’t take Ranjha across since he cannot afford the fare. “The boatman tells him that since he has no money, he could very well sink Ranjha in the middle of the river,” Soofi says. “This is his encounter with the merchant class, with commercialism and capitalism.”

In Jhang, Ranjha comes across a resort of sorts that is owned by Heer. When she gets word that a stranger has intruded on her property, she is enraged and confronts Ranjha.

They fall in love, but the romance is doomed. Heer’s family has betrothed her to another, and a local priest tries to coerce Heer into getting married to this man by misinterpreting the shari’a. This is where Heer’s headstrong nature comes into play. The priest pleads and quotes from scripture, but Heer never assents. And so, the religious order of society intervenes once again in their lives.

Heer never accepts her farcical marriage, which she neither believes in nor consummates, and remains loyal to Ranjha. Their case ends up before a judge, where Heer eloquently presents her own defense. But the judge sides with Heer’s family and the couple is bested by the Sials; Heer’s uncle poisons her before she can finally marry Ranjha.

Sahibaan, also from a sub-clan of the Sial tribe, met a similar fate. Her love, Mirza, from the Kharal clan of Danabad, fought off the Sials with the help of arrows and his trusted steed, Bakki. Mirza, an expert archer, eloped with Sahibaan. They managed to reach Danabad, only to be chased after by Sahibaan’s relatives. According to Soofi, Sahibaan’s relatives killed her after killing Mirza. But the caretaker of the shrine, a descendant of Mirza, says that Sahibaan’s clan took her with them to Kheewa, where she committed suicide. In his version, Mirza’s ancestors exhumed Sahibaan’s body and brought it back to Danabad, where she is buried next to Mirza and his father in a rudimentary shrine.

While Heer and Sahibaan have been immortalized by the poets and writers of the subcontinent, the Sials never forgave either woman, according to local legend. To them, Heer and Sahibaan remain the women who sought change and choice, defying their powerful families and abandoning their riches. Caretakers at their shrines say that the Sials have never visited the graves of Heer and Sahibaan.

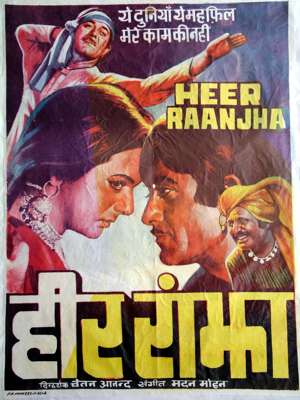

Poster from the 1970 film Heer Ranjha, based on the centuries-old legend of the doomed lovers. Via wikipedia.

In his 2008 paper on sectarianism in the district, academic Tahir Kamran noted that after the murder of SSP founder Haq Nawaz in 1990, “The cry Kafir Kafir Shia Kafir (Infidel, Infidel Shia Infidel) reverberated around Jhang. Thereafter, sectarian militancy became synonymous with Jhang, displacing the long-standing cultural eclecticism, sectarian mutuality and compassion amply symbolized in the romantic tales of Hir [sic] and Ranja:, Mirza Sahiban and the poetry of Sultan Bahu. Love and romance were replaced with hatred, and peace with ‘tit-for-tat killing.’”

Hundreds of years have passed since Heer and Sahibaan fell in love in the fertile land of Jhang. But Heer’s strong will and her defiance still strikes a raw nerve amongst her descendents. In 1970, the film Heer Ranjha was released in Pakistan. Loosely based on Waris Shah’s verses, Heer Ranjha starred popular actors Ejaz Durrani and Firdous, and featured Noor Jehan, one of the subcontinent’s most iconic singers, on the soundtrack. The film – which Soofi calls a “vulgar” adaptation with none of the complexities of the characters – was a hit in Pakistan, but in Jhang, the film clearly rubbed the Sials the wrong way. They were adamant: the screen adaptation of Heer’s life would never premiere in the district.

“There was a massive fight among the Sials and the Jatts (Ranjha’s clan),” Hussain recalls. “Lots of bullets were fired, people were injured… there was a Shia/Sunni clash. They did not allow the film to be shown.” (Pakistani-British author Nadeem Aslam said at the Karachi Literature Festival that he was so moved by this episode that he decided to name a fictional city in his latest novel after Heer.)

To understand how patriarchy and love battle it out in Punjab, one must go to the shrine of Heer Ranjha.

I’m not sure what to expect as I walk up the steps and take off my shoes at the door. I’ve heard the bare essentials of the legend; we all do as kids in Pakistan – there are enough mentions of it in poetry and songs for one to recognize the reference. But I have always thought the story to be more fiction than fact. After all, unconditional, enduring love doesn’t exist; or perhaps it did. After all, the evidence is right in front of me.

The doomed lovers were buried in one grave, now encased in the stunningly beautiful Mai Heer Darbar. Heer’s shrine is located down a winding lane on the outskirts of Jhang. Men and women walk down the lane, where a graveyard surrounds the gravesite. An unassuming tiled façade makes way for a shrine that celebrates love. There is none of the darkness here that awaits women who have tried to marry against their parents’ will, who are still hounded, like Heer and Sahibaan. Sunlight streams from the open roof and shines down on the grave of the lovers. The walls are painted in a riotous array of color, completely different from the greens and blues and ornate mirrored inlays that dominate Sufi shrines in Pakistan, or the ivory marble of the world’s most iconic monument to love, the Taj Mahal. The raised grave is covered in an embroidered chador of pink and yellow, emblazoned with the name of Heer and Ranjha.

I am still at the doorway, trying to comprehend the scene, when a woman walks past me, flings herself on the grave and prays. She gets up and walks around, feverishly praying in each corner. She glances at me, an outsider with a camera and a notebook, but remains focused. Her prayers completed, she leaves and another group of men and women enter the shrine. Incense wafts from a corner, and devotees leave money for the shrine’s upkeep on their way out. In the past, people took mud from the shrine, until the outer section was closed up to prevent them from doing so. I leave the shrine imbued with hope; perhaps, in those feverishly whispered prayers, there is still the possibility of pure, unconditional love exists.

Unlike Heer Ranjha’s shrine, Mirza Sahibaan’s grave is not easy to reach. One drives by acres of wheat fields, over a gushing canal, and through winding neighborhoods plastered with election campaign posters before coming across a one-room building with a small dome in an open field.

This is the shrine of Mirza Sahibaan, built right next to the spot where Mirza was slain in his fight with the Sials. It is located in the sub-district of Jaranwala, Faisalabad.

The shrine is a simple concrete structure that has none of the glowing aura that exudes from Mai Heer Darbar, which has stayed with me for days. There are separate graves for Mirza, Sahibaan and Mirza’s father Rai Khan Kharal. Vilayat Ali, the caretaker of the grave, says his grandfather saw Mirza in a dream and he told him to take care of the graves. And so, the family now lays claim to this one-room shrine. Every spring, there is a small carnival in Danabad to celebrate Mirza Sahibaan. Ali points out the graves, the incense burning, and the old tree where Mirza rested, according to local legend, as well as the grave of Bakki, Mirza’s horse. “Mirza and Sahibaan…there was this ‘action’ between them,” says local resident Khadim Hussain Allahyar, who says the tale of Mirza Sahibaan has passed down through generations in Danabad.

Soofi notes that there is something unique about this iconic tale that isn’t found in any of the other epic romances: that Mirza tells Sahibaan that she shouldn’t love him just to reciprocate his feelings. “He is giving her the choice – love me for me, not because I love you. This democratic right isn’t in any of the other epics.”

This right is still relevant. Heer and Sahibaan’s struggle to choose the man they want to spend their life with is a tale that is repeated across Pakistan, where forced marriages and conversions of Hindu and Christian girls to Islam have ended up in court. Courtships are broken off because of religious, financial and caste differences. In the Sindh province, where women can be killed for ‘dishonoring their family’, newspapers carry announcements by girls declaring that they have married someone by choice. Justices of peace conducting civil weddings ask women to testify that they are not under the influence of drugs, and have not taken anything from their house, but are marrying of their own will.

Reworking the legend

Despite – or perhaps, because – Heer and Sahibaan stood for their right to choose who they loved, their stories are still twisted in patriarchy. For example, Mushtaq Soofi notes, Heer has been dubbed as Mai Heer—Mai is an honorific for women—to make her appear like a ‘married’ woman, and therefore acceptable in society. Hundreds of years of retelling have added more patriarchal elements. In Danabad, Vilayat Ali notes that Sahibaan had eventually “sided with her family” and had broken all but four of Mirza’s arrows so that he wouldn’t kill her family, who was chasing the couple.

Syed Abid Hussain, the government-appointed caretaker of Heer and Ranjha’s shrine, has his own version of the saga. “They are the true lovers of God,” he declares. There is a tradition of looking at verse through two lenses: as devotional poetry for God or as poetry for the object of one’s affection. In Hussain’s version, Heer and Ranjha’s love for one other is superseded by their love for the divine.

He sits by the foot of the grave and watches the visitors walk in and out. But there is a kind of visitor he does not like.

Over the years, Heer has seemingly become an inspiration to women who believe they, like her, have found the man they are destined to be with, much to Hussain’s dismay. The shrine and its adjoining graveyard are frequently used as a spot for couples to meet and elope. “I see this all the time,” Hussain says. “Just the other day, there was a girl who kept sitting in the shrine for hours and hours. I eventually asked her if she had a prayer or some such. She said ‘I am waiting for someone’. I told her that this was a graveyard; it was no place to wait for someone. But soon enough, I saw this boy drive up on a motorcycle and the girl went off with him.”

According to Vilayat Ali, there is only one noted account of an elopement at the shrine, which had offended villagers because the woman in question was married.

But aren’t these couples, too, following in the footsteps of those buried together in one grave in this shrine, the enduring sign of their commitment to each other?

“No, they loved God.” Hussain is adamant. “These couples… the situation these days has become very bad, I feel. Girls meet boys over mobile phones. This is someone’s son, someone’s daughter. Their families don’t know what the children are up to. This isn’t right. We don’t want that someone’s daughter is mistreated.”

To deter more couples from hanging around the shrine and the graveyard, Hussain said a police constable was assigned to chase away couples.

‘Not to arrest them?’ I ask.

“No, but of course the police can and have arrested couples. They put the man in the men’s lock-up, the girl in the women’s lock-up. They can also arrange for their marriage by convincing the families – the police here do arrange marriages, you know.”

Despite what Hussain says, the women who are visiting the shrine want what Heer died for: love. The wooden spires surrounding the raised grave are testament to this desire. Each spire is covered with glass bangles tied to it with thread. This is the mannat – the wish – that unmarried women attach to the shrine. The bangles represent the desire to find love, to be wed. Punjabi women generally wear a set of gold bangles to identify themselves as being married, in lieu of a ring as is traditional in the west. “There has to be a set of two bangles,” Hussain explains the logic behind the ritual, “because the girl is asking to be a couple.” Once their wish has been fulfilled, the women untie the thread and the bangles.

Many call on Heer to have their prayers for a child answered. On a brutally hot April day, Sabira Bibi has travelled from the southern district of Bhakkar to pay her respects at the shrine. “We asked God for a son,” she explains. “I now have one; I’ve come to thank her.”

But where these women rely on prayer and offerings, Heer struck her own path. It was not just her defiance and struggle against the state, religious authority, and the powerful familial structures. Heer understood the system and how to subvert it; she employs Ranjha as a caretaker or has him serve as a mystic because she knows it is acceptable for him to be near her in these guises. Ranjha tells Heer that they should elope early on in their courtship, but she refuses; she wants to reform the system, to work within it and beat it, and it is only when she has exhausted all her options that she consents to an elopement.

Heer has inspired several legends of her own. One says that Heer’s shrine is untouched by the elements. “That isn’t true. It rains here just like it rains everywhere else” Hussain remarks wryly. In Rajasthan, Heer Ranjha is reportedly recited to cows during a drought. In Danabad, the caretaker of Mirza Sahibaan’s shrine proclaims that Mirza received an award for his archery prowess in the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar. Another legend says that every year, a girl is born in Jhang who looks just like Heer, but she dies. “These myths are testament to Heer’s iconic status,” Soofi says smilingly. “It inspires this.”

And so – in spite of the opposition from their ancestors and self-styled guardians of morality in Pakistan – love thrives in the shrines of Heer and Sahibaan. It survives in the verses that set the tone for their stories to become legends, in the open fields where men argue over their history as if they were eyewitnesses, and lyricists write songs about the women as if they knew them intimately. More importantly, their memory persists. And that is something that no marauding mob chanting for death to infidels or politicians dispensing largesse for votes can ever hope to destroy.

Saba Imtiaz is a freelance journalist in Pakistan. She reports on politics, culture, human rights and religion for local and foreign publications and is currently working on a book about the conflict in Karachi. Her work is available on her website, http://sabaimtiaz.com and she can be contacted at saba.imtiaz@gmail.com.

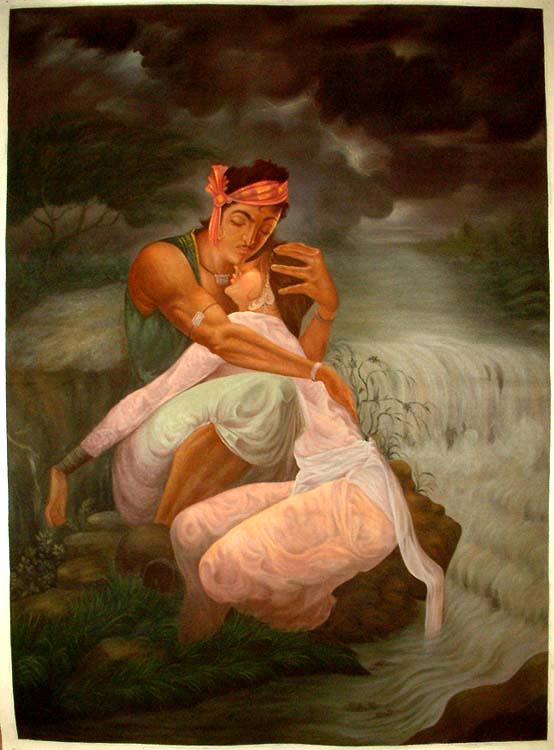

Featured image via http://www.tumblr.com/tagged/ranjha