By Don Jolly

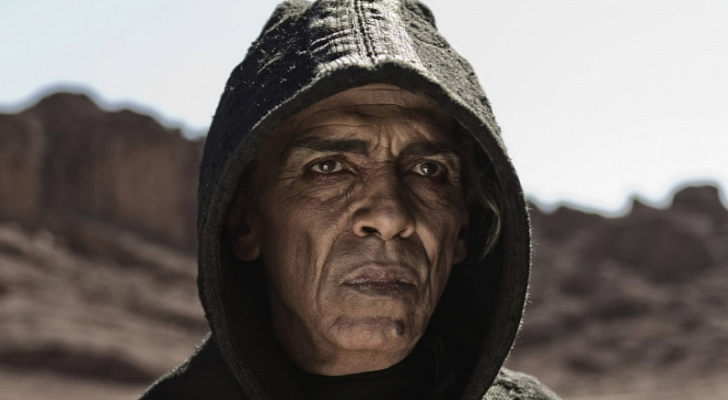

Imagine: the Moroccan desert, twilight, shot from a flat and uninspiring angle. Enter Samuel (a scraggly British character actor in a false beard), shivering somewhere between “lost” and “confused” as he navigates a dune. He sees a young shepherd boy, staring blankly at his rented sheep.

“You! Boy!” says Samuel, with gravity. “What is your name?” Strings begin to build on the soundtrack. The camera begins zoom precipitously toward the boy.

“Name?” he responds, incredulous, in a voice like Tiny Tim. “My name is David, sir!” His face fills the frame. Cut to black. A portentous “thump” is heard, a riff on Hans Zimmer’s Batman scores. “The Bible,” says the screen.

Then: an ad for laundry detergent.

The preceding, or something like it, is the regular beat upon which the History Channel’s miniseries “The Bible” goes to commercial. It’s also the only truly successful beat in the show – although it is doubtful that the producers intended it to be as funny as it is. Part of the humor, of course, is the me-too shoddiness of the thing: the Batman score, the computer-generated logo of cracked bronze. But a bigger portion has to do with the nature of the dramatic moment chosen as the regular “cliffhanger.” Almost without fail, “The Bible” breaks its acts at moments where we are introduced to important characters, or major events are just past the point of being set in motion. Daniel enters the lion’s den – The Bible! Samson, meet Delilah – The Bible! Jesus begins his ministry – The Bible!

These moments – there’s no word for them yet – are such a common occurrence in summer blockbusters that their use here stinks of cliche. These are “Obi-Wan Kenobi, meet Anakin Skywalker” moments, after a line from the Phantom Menace trailer. They serve to both comfort and unsettle the audience, for they remind us that we know where things are going, narratively, and usually, that they will go sour. When we see eight year-old Jake Loyd shaking hands with Obi-Wan, it is in the shadow of our foreknowledge that later – as Darth Vader – he’ll be responsible for the murder of his mentor. Such moments remind us that this story has been told before, and its content is disaster. “The Bible” is suffused with them.

There is always something jarring about seeing the biblical text cut-up and rearranged to fit the strictures of some pop-cultural idiom. John Huston’s 1966 adaptation of the first 22 chapters of Genesis (The Bible: In the Beginning) gave me a similar laugh when its trailer announced, enthusiastically: “The BIBLE! The magnificent book of humanity is now a film!” But Huston’s work at least attempted to present itself as a work of spectacle, emphasizing its performances, special effects and expense. 2013’s “The Bible” is in the position to do no such thing. It’s a cheap show and looks it. It is also unwaveringly self-serious, a tone undercut by the fact that its earnest actors are forced to toil in phony armor and ridiculous make-up. What it offers in place of spectacle is the solemn promise that there will be no “lecturing” the audience, to quote producer Alan Burnett. This “Bible” is meant to be exciting. As Emma Allen says in her recent New Yorker piece on the subject: “the stories the show recounts are heavy on gory battles, semi-nude women and melodrama.” These are all things at which television excels, so what, exactly, is the problem?

Episode 3, “Hope,” which aired on the 17th, demonstrates a few. The first half-hour begins by recounting the start of the Babylonian exile (drawing on 2 Kings) and then following Daniel’s miracles and prophecies until the end of captivity under the Persian king Cyrus in 538 B.C.E. It is sloppy midrash. Many characters are combined, deleted or substituted for one another, either for narrative reasons or strictures of time. The Book of Daniel’s final Jewish monarch Jehoiakim becomes, for example, the faithless Zedekiah depicted in 2 Kings and the Book of Jeremiah. Darius the Mede, the king who oversaw Daniel’s adventure in the Lion’s den, is here explicitly identified with Cyrus, a hint that Burnett may subscribe to the interpretive arguments of Donald Wiseman. Following a blatantly Christian reading of Daniel 7, the narrative shifts to establish a culture of rebellion in Roman Jerusalem, drawing lightly on Maccabes but displacing the role of Antiochous IV directly onto Herod the Great. The stories of the Gospels are given a political bent: Mary’s annunciation occurs during an anti-Roman riot, for example. In another scene Joseph, Mary and a precocious young Jesus pause on a sun-baked road to stare significantly at a crucified man on the hill above. Something must be done, says Mary, as the camera pulls tightly onto her child. The episode ends after Jesus has recruited Peter. “What next?” asks the Apostle. “We change the world,” says Jesus, heavily, and the next episode’s preview makes it clear that he is speaking politically. We are left with the promise, through brief preview clips, of civil unrest.

Burnett has gone on record as viewing this series as a balm on “Biblical illiteracy” (this comes from Emma Allen in the New Yorker, again). From a scholarly perspective, it is hard to agree. By streamlining the Biblical narrative, Burnett and company make it seem as if the biblical text is as “settled” as their rendering of it is. “The Bible” (2013) is a clearly delineated narrative, with a consistent history and a payoff for every foreshadowed set-up: right down to the young Jesus regarding the cross as an empty space in need of occupation. Still, it is perhaps asking too much of prime-time television to embrace the multi-vocality of the original text. What’s more, it’s clear that reading this work as scholarly is missing the point: it’s emphasis is on entertainment, after all. It should succeed when judged on those standards.

It should – but doesn’t. The Bible’s appropriations from other pieces of pop culture are not restricted to the moments before a commercial break. In “Hope,” for instance, Herod the Great is depicted as a blatant riff on David Lynch’s version of Vladimir Harkonen, complete with body-horror (here delivered by leeches) and booming, scenery-chewing monologues. He is, however, not airborne. A scene drawn from Jeremiah 19:9 depicts the cannibalism of Jerusalemites under siege with the dimly-lit, lunging close-ups one expects from the degenerate age of zombie film. “The Bible” is a hodge-podge of effects and devices that have worked before, jrtr thrown together cheaply and haphazardly.

It’s bad television.

There are some decent shots in the third episode. The occasional digital composite is executed with aplomb, and some actors make out well with the meager material they are given. Nebuchadnezzar is appropriately villainous, for example. But so far, “The Bible” is content to say nothing heretofore unsaid, to tailor itself to the exact flavors and formats of the public imagination in 2013. The real story, in both the production and success of this miniseries, is the failure of that imagination – and that public. When Glenn Beck identified “The Bible’s” gray-skinned Satan as a Barack Obama analogue, he was according the series a political complexity it has done nothing, thus far, to earn.

Still, in the tenth of a second before it goes to commercial, “The Bible” is really, really funny.

Don Jolly is a graduate student in New York University’s Religious Studies Program.