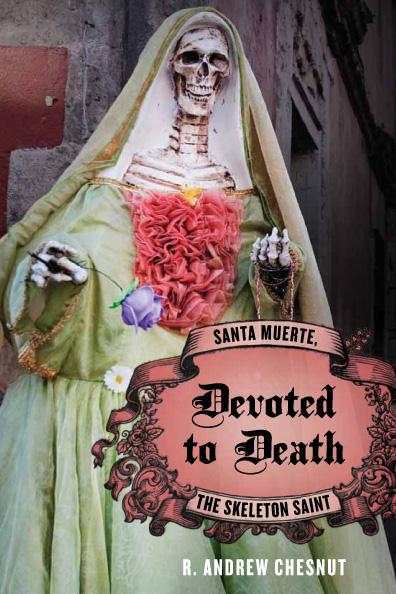

A conversation with R. Andrew Chesnut and an excerpt from his new book, Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, The Skeleton Saint.

By David Metcalfe

One of the most contentious emergent religious phenomena in recent years has been the increased public presence of Santa Muerte, Saint of Holy Death, a Mexican folk saint whose skeletal visage is sweeping across the Americas. With her many devotees among society’s dispossessed she’s drawn the ire of orthodoxies, both religious and legal, and has become a beacon for the media, heightening the lurid glow of stories covering immigration and the drug war. A new book by Dr. R. Andrew Chesnut, Bishop Walter Sullivan Chair in Catholic Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint (Oxford University Press, 2012) is one of the first academic studies in English of this complex and controversial figure. He was kind enough to answer a few questions and provide some insight into this fluid and fast growing devotional tradition.

The media portrayal of Santa Muerte is often tied to drug violence. How did that affect you as an academic researching her devotees?

As a specialist in Latin America history, I had done research before in dangerous areas. A lot of the research was conducted at the main shrine in Mexico City, where I know the owner pretty well, Dona Queta, the famous devotional pioneer. So even though it’s one of Mexico City’s most notorious barrios I felt like she and others, and maybe possibly the Boney Lady herself were watching my back. Although I did take all the precautions that I could.

One of the aspects I really enjoyed about your book — and above you say “possibly the Boney Lady herself” — is that you’re able to capture a similar respect for her devotees. How is that being received by readers?

Devoted to Death came out in January and is the first academic book in English on Santa Muerte. So far the reviews have been positive. Until now most of the accounts of her have been by journalists, and many of them seeking to play up her dark side, the Santa Muerte of the black candle and such. So yeah, I think there’s an appreciation of my underscoring her complexities and her multi-faceted identity.

I’ve noticed that the media covers Santa Muerte differently than they do other devotional phenomena. It seems journalists are pushed to recognize her as a physical being. Often they don’t talk about her phenomenon as though people believe in Santa Muerte; journalists fall into saying, well Santa Muerte does this, or attracts that, as if they are discussing a real being.

I think I did that as well, but I did it intentionally to convey that, for her devotees, she very much is animated, she’s a living saint. I think it’s a rather natural tendency to think so.

She’s often referred to as a female, she has a female identity, so you’ll see that I often refer to her as ‘her.’ I was aware of what I was doing in the book, but I felt like it made sense because I was trying to excavate and highlight how her devotees view her.

In fact, to add to that, an academic journal sent me an article submission on Santa Muerte to review and the authors, while acknowledging her female identity, constantly referred to her as it. That struck me as odd.

The way media tend to treat even the practice of, for instance, burying a St. Joseph statue upside down for good luck selling a house, is very different from how they treat Santa Muerte. Do you think that the media are aware of the role they play in defining how devotees see these rituals? Do you think their coverage is a part of how belief in Santa Muerte developed in people’s awareness, in their practice?

That’s a good question, I don’t think I can answer that because it would require being in their heads. But I guess what strikes me is that so much journalistic coverage is really superficial. It’s people who know nothing about the topic. They’ll talk to me, they’ll do a cursory Google search, and the next thing they’re writing articles about it. That’s how a lot of journalistic coverage of my stuff is anyway.

There’s another reason why it’s mostly only been the black candle side highlighted by the media. As you know most media is profit driven, it’s commercial media, so they want to sell their product and violence sells.

The African Diaspora and Afro-Latin traditions seem like they’re very porous. How far south does Santa Muerte’s influence reach? Does she have influence in South America? Has her devotion been integrated into traditions like Candomblé as well, or is she more of a Mexican phenomenon?

Santa Muerte is present in all of Central America. I personally have seen altars to her in Guatemala. When I was In Cusco, Peru a couple of summers ago, I found some of her incense at the big public market there in Peru. I know she is in Venezula.

I spent a month in Brazil this summer, and no, she hasn’t been integrated into Candomblé or any of the other Afro-Brazilian religions yet.

Both here and in Mexico there’s a fair amount of integration with Cuban Santería. I think what you see in terms of the Afro Diaspora religions is a hybridization taking place in Mexico City.

**

An excerpt from Chapter Four of R. Andrew Chesnut’s Devoted to Death, “Red Candle of Love and Passion,” pp. 129-31.):

Beyond the standard love-binding prayer printed on the back of thousands of votive candles of all colors, there are specific rituals that those seeking a miracle of the heart can perform to increase the chances that Saint Death, the most powerful of love doctors, will give heed to their pleas. And I’m still amazed that I don’t have to look any further than my own social network in Richmond to find someone performing such rituals. Lupe, the thirty-four year-old mother of one of my wife’s third grade students, came to Richmond with her husband, Miguel, eleven years ago from the north-central Mexican state of Zacatecas. Married at age thirteen, she complains bitterly about her husband’s domineering ways. For example, he might be gone from their tiny apartment for four or five days and then return to demand a full accounting of Lupe’s whereabouts during his unexplained absence.

In January, 2010, Miguel was detained by ICE agents in Arizona, where he had gone to wait for a relative from Zacatecas who was attempting to cross the border into the U.S. with the help of “coyotes” (smugglers). Having been deported, Miguel is now back in Zacatecas and has no immediate plans to try to return to his wife and children in Richmond. In the meantime, Lupe has wasted no time in asking Santa Muerte to work her powerful love magic, but not to bring back Miguel to her side. Rather, the ritual she performs, right out of the pages of the Biblia de la Santa Muerte, is aimed at finding a new man, preferably a gringo like the boyfriend of her Salvadoran friend who doesn’t mind if she goes out dancing on weekends without him.

Of the four love-related rituals recommended in the Saint Death Bible, Lupe chose the one described as “For Luck in Love” (Para tener suerte en el amor) as the most appropriate. Like most Santa Muertistas, Lupe has adapted the ritual to fit her own needs and resources. In parenthesis I note the changes she has made to the prescribed ritual.

Ingredients:

1 small, bone-colored Santa Muerte statuette (red)

1 white plate

Petals of 3 red roses

1 bottle of rose oil (patchouli)

1 bottle of cinnamon oil

1 bag of red fabric (red tee shirt)

1 10 cm x 10 cm piece of personal clothing (red tee shirt)

1 piece of a binding stick (a twig found on the ground)

Matchsticks

Water

1 strainer

1 bucket

Procedure:

Put your article of clothing in the middle of the plate and immediately place the Santa Muerte on top of the clothing and then cover her with rose petals (lay her down if it’s easier). Drizzle the rose and cinnamon oil over the petals and then put the binding stick on top.

Cleanse yourself from head to toe with a red votive candle lit with the matchsticks. Pray the Santa Muerte prayer (you can use the Santa Muerte prayer that best suits you). When the candle burns out, remove Santa Muerte and wrap her up together with your article of clothing in the red fabric.

Put the wrapped plate and binding stick into the red bag. Then put the rose petals to boil. Once it has boiled, let the water cool down and then use it to rinse yourself after bathing. You should always carry this amulet (the bag) with you and shouldn’t let strangers or acquaintances touch it. Remember that the baths are from the neck down.

Lupe has performed the ritual twice, and is still waiting for the Bony Lady to come through with a bolillo (literally, white-bread roll but Mexican slang for gringo).

R. Andrew Chesnut is Bishop Walter Sullivan Chair in Catholic Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is also the author of Competitive Spirits: Latin America’s New Religious Economy (Oxford University Press, 2003) and Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty (Rutgers University Press, 1997). He also blogs for the Huffington Post.

David Metcalfe is an independent researcher, writer and multimedia artist focusing on the interstices of art, culture, and consciousness. He contributes to Evolutionary Landscapes, Alarm Magazine, Reality Sandwich, Modern Mythology, The Eyeless Owl, and is currently co-hosting The Art of Transformations study group with support from the International Alchemy Guild. Metcalfe is Books Editor at The Revealer.