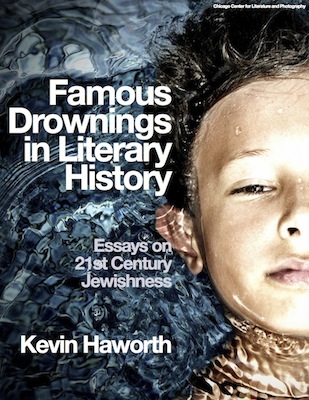

An excerpt from Famous Drownings in Literary History: Essays on 21st Century Jewishness by Kevin Haworth, published by Chicago Center for Literature and Photography. Read a review of Famous Drownings from Chicago Tribune here. You can find out more about Famous Drownings here.

My wife, a young and quite beautiful rabbi, knows a lot about the plagues. She knows, for example, that the ninth plague, hoshech, was not just darkness for the Egyptians, but complete isolation and imprisonment. The darkness was so pregnant and heavy, she tells us on the way home, that it had force, even weight. Once it descended upon the Egyptian houses no one could move. It blocked every sound. Everywhere was thick and absolutely black and so heavy that it held the Egyptians down in their chairs like chains or pressed them against the walls. Each of them alone, terrified in the dark, with only their own thoughts for company.

And the frogs! she says. They were everywhere. In the food. In the cabinets. In your underwear drawer. And all of them croaking, all at once. Fat bullfrogs and tiny tree frogs and squat ugly bellowing toads. Blasting every street and courtyard and bedroom with their terrible sounds.

Have you heard a frog? She asks our son in the backseat. He has. He agrees that they are very loud.

So you can imagine how painful this noise was, she says. My son loves this midrash, the Jewish tradition of re-

telling and adding to stories. He loves their texture and their details, their inherent creativity. He wants to know more about how the Egyptians suffered. The burns from the hail, the itching from lice bites. The terrible rank smell of their dead cattle. How they could have endured all this, nine times, and not let us go.

He is not the only one to want to know more. In March 1936, a young Jewish poet named Muriel Rukeyser traveled from New York to West Virginia to document the effects of a plague.

Six years before her journey, in a place called Gauley Mountain in the West Virginia countryside, work had begun on a tunnel to re-route the fast-running New River, sending it downhill hundreds of feet so that the force of its descent could be captured by turbines and converted into electricity. Such projects were not uncommon in Appalachia at the time. Once the drills started, the rock inside the tunnel was found to be rich in a valuable substance called silica and the project was expanded. The tunnel was widened beyond what was strictly necessary to divert the river; the silica was collected by dry drilling, a quick and cheap method that threw clouds of dust in the faces of the men performing the work. The laborers consisted of uneducated local white workers and unemployed black men brought in from as far away as Kentucky and Ohio. They breathed this dust and they began to cough. Then, over the next months and years, they died by the hundreds.

Rukeyser wrote twenty poems about Gauley Mountain: landscape poems and historical poems and monologues in the voices of wives and caretakers and documentary poems of a kind rarely seen before — angry transcripts of testimony in front of Congressional committees, quotations and accusations of witnesses, cut and stacked together like geologic strata. She titled the sequence The Book of the Dead, remembering the Egyptians, the complicated series of spells and incantations they slipped into coffins to help their dead wander through the afterlife.

Last year there were nine plagues. My son was three years old then, and in his interest in dump trucks and washable paints and birds outside the kitchen window there was no room for the finality of suffering. But this year death has entered his vocabulary anyway.

It is a few weeks before Passover once again in Appalachian Ohio, located just a few miles from the West Virginia border. My wife and I are standing in the kitchen, preparing for the holiday. It is a lengthy job to make a kitchen Passover-ready, involving a complete exchange of every dish and utensil, taping shut the drawers for the dairy dishes and silverware, pushing back the meat dishes to where they can’t be reached, even by accident, then going down to the garage and unearthing from dusty cardboard boxes the separate sets of Passover dairy plates and Passover meat plates, then back to the kitchen again, where we run the dishwasher through, completely empty, to clean it of any bread residue, then wash, in separate loads, the dusty dishes — all of this preparation for eight days of repeated meals of matzo and butter, matzo and cream cheese, and those terrible hard bits of unleavened cereal that the children will eat once and then push away every morning for an entire week.

Children make it difficult to observe Passover. They love the holiday festivities but hate the diet. We are standing in our unprepared kitchen, asking ourselves, Can they possibly eat matzo for a week? Then the phone rings. It carries the news that one of my wife’s congregants, a professor’s wife, has died from the sudden and fierce onset of kidney cancer.

She was fine — we saw her just a few weeks ago. Then she began to experience a crushing pain. Now she’s dead.

We live in a young community — a town filled with college students, mostly — so funerals are rare. But already on the phone I hear my wife’s professional voice kick in. She is brilliant at funerals. Death does not scare her. During her rabbinic schooling she served as a chaplain at an inner-city hospital in Philadelphia. She was assigned to the neonatal intensive care unit, the saddest place in the hospital, where young mothers waited for their tiny premature babies’ lungs to inflate, their hearts to grow enough muscle to push blood out and back through their small bodies. Often they did not.

She would leave in the morning in her prim cardigan and long skirt, uniform of the modest clergy, and come back late at night, tired and worn from long hours of attending the slow death of the youngest people in the world. She would sit at the sides of African immigrant women and Haitian women and Puerto Rican women while they prayed, in their respective ways, for their shriveled premature children, incubated down the hall. I don’t believe in Jesus, she said once, as we sat at the table in our small apartment, after one of these long nights. But I see why somebody would want to.

Now, on the phone, she efficiently navigates the conversation from condolences to logistics. Per tradition, the funeral must be as soon as possible. There is the funeral home to inform (her job) and relatives to summon (theirs), academic departments to notify. A phone tree will bring the rest of the community out on Tuesday, at one o’clock in the afternoon, shiva to follow at the home of the deceased.

For the Egyptians, death marked not the end of struggle but the beginning. Their afterlife was filled with hazards. One could be devoured again by a crocodile or mauled by a hippopotamus. One could be called before the terrible figures of Atum or Ra and asked to testify to the value of one’s existence. One had to know how to leap onto the celestial barge that rode the ‘four steering- oars of the sky’ into the Otherworld or risk being left behind forever. Journeying through this Otherworld required knowledge; to help, one’s coffin was filled with slips of instructions written on parchment and provided by relatives. Scholars refer to those phrases as The Book of the Dead.

The black victims of the Gauley Mountain industrial disaster, excluded from the white cemeteries, were driven out to a cornfield. Doctors paid by the company sent home to the men’s wives false lung diagnoses of pneumonia, tuberculosis, pleurisy; anything but silicosis. In the middle of the night, the funeral director drove the bodies into the open field in his hearse. Rukeyser writes: blind corpses rode/with him in front, knees broken into angles/head clamped ahead…/He buried them in rows of five.

In the Jewish tradition, there is no Egypt, only Mitzrayim, from the Hebrew word for narrow. On Passover we tell of our journey out of Mitzrayim, that narrow place of rules and force. The plagues cracked open that narrow world and we walked to freedom across a wide desert, stopping along the way at Sinai to receive the knowledge of the world.

The rabbis tell a midrash about this moment, the giving of Torah at Mt. Sinai. After so many years in slavery, we could no longer understand Hebrew, only the language of our oppressors. Thus the first words that God spoke to Moses were in Egyptian, switching to Hebrew to signify the change from slavery to liberation.

The words that God spoke, in Egyptian, were I am.

The funeral is well-attended, despite a late spring heat wave that has joined us from over the West Virginia mountains. There are many graveside mourners, but the deceased woman’s brother catches my eye. He sits quietly under a shade erected for the closest family members, right next to the open grave, while the rest of us loosen our ties in the hot sun. His face is tiny, wrinkled — like a little Jewish gnome who has crawled out of the forest to bury his sister. He looks at the casket with sad eyes. By contrast the widowed husband is stoic, impassive. All of this is just washing over him. He is so calm that he is making people nervous. Everyone wants more.

There are many different ways to mourn.

As my wife leads the funeral, the brother loses his composure. Beneath the mask of his heavy brown beard he looks much like his dead sister. He sobs quietly as her friends cite her generosity, her giving to the arts and social services, her steadfast friendship as they themselves lost husbands or wives to divorce or death. He cries, his beard bobbing, as he stands and stumbles through the kaddish. He cries as he turns over the shovel and throws dirt into her grave and cries when he hands the shovel to his brother-in-law, as a single coffin is lowered into a single hole.

After the funeral, we pick up the children from school to attend shiva. This too is part of their education.

Who died? My son asks from the back seat. Someone’s friend.

His good friend?

His very good friend.

Oh, my son says. He looks out the car window at the blue spring sky.

I had three sons who worked with their father in the tunnel, a mother tells us in Rukeyser’s poem “Absalom.” Shirley was my youngest son; the boy. Shirley’s father dies from silicosis, then his two brothers as well, an entire family choked to death in a few months’ time. After eighteen months working in the tunnel, the boy, 17, can no longer breathe well enough to stand up. I would carry him from the bed to the table, his mother says, from his bed to the porch, in my arms.

Rukeyser writes: I open out a way, they have covered my sky with crystal….I force a way through, and I know the gate/I shall

Two days before Passover. In the basement of the synagogue, my wife stumbles upon a little box of Jewish kitsch. She was downstairs, looking for a water leak — this is the rabbi’s job in a small town — when she found a cardboard box of items from the Lost Age of Hebrew School. Inside the box, unopened for many years, lie felt menorahs and make-your-own driedel kits and holiday flash cards, and there, at the very bottom, a bag of children’s masks, ten total, one for each plague. She brings them home and we take them out of their cellophane wrapping.

There is a green mask with rolling froggish eyes, a red mask in the shape of drops of blood. The mask for darkness is a black cloud over a burning orange sun; hail is a line of fire, like a science fiction invasion, charging across the forehead. The masks, despite their undeniable strangeness, are cute. The mask solemnly labeled ‘First Born’ indicates death as Xs over the eyeholes, like a 1930s comic strip.

My wife calls the children and they grab the masks, eager to play. They run around the house wearing the plagues as their faces. They are the hail that burned the Egyptians. The darkness that smothered them. And they have been liberated by these disasters, freed from Egypt thousands of years ago.

The company that sent the men into the Gauley Mountain tunnel was the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation, based in Chicago, and whose operations at that time were limited to the United States and Europe. Later they would open a plant in India.

This is the region of the breastbone, Rukeyser writes. This is the heart (a wide white shadow filled with blood).

According to Rukeyser’s FBI file, 121 pages long and initiated because of her association with writers’ groups of ‘Communistic’ tendencies, The Book of the Dead “deals with the industrial disintegration of the peoples in a West Virginia village riddled with silicosis…she is against everything in any organization which represents the brutal life of enforced regimentation and national slavery.”

You can find out more about Famous Drownings in Literary History by Kevin Haworth here.