Part 3: Compromise and Conversion

This post is the third in a series comparing the epic lives of Sundiata, medieval Malian ruler, and Iyad ag-Ghali, a power player and leader in Malian rebel movements for nearly forty years. You can read part 1 here and part 2 here.

by Joe McKnight

“He already had that authoritative way of speaking which belongs to those who are destined to command.” – D.T Niane

Sundiata became even more exacting, and the more exacting he became the more his servants trembled before him. – D.T Niane

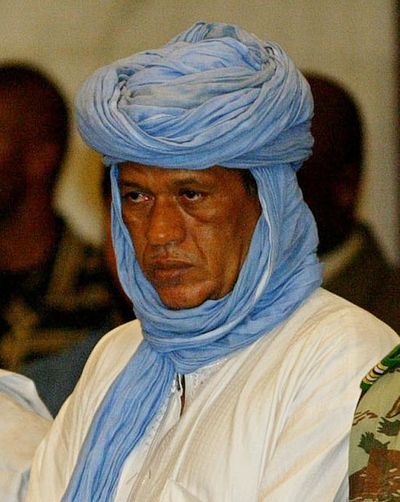

Algeria’s secret services may have had Iyad’s number, as English anthropologist Jeremy Keenan put it, but in 1990 he got a call from home in the form of another armed rebellion against President Traoré’s government in Bamako. Iyad was there from the start as a key leader of the rebellion, and by 1991 he was a lead negotiator in peace talks with the government. As peace settlements will do, this one displeased some of his fellow rebels, nor their civilian constituents: too many compromises, some felt, too much trust in the promises of the Malian government, and too little commitment to the dream of an independent Tuareg-majority state. And all had good reason to wonder if there might have been something extra in the deal for Iyad, who went on to hold appointments and advisory roles to the government in Bamako. His constant central role in the ongoing rounds of negotiations, settlements and failures throughout the 1990s earned him a lingering distrust among northerners, who still see him as a government collaborator or a rogue agent in it for the money and advancement. The most widely cited Wikileaked U.S. Embassy cable regarding Iyad, issued in October 2008, makes the assessment that he “continues to cast a shadow over northern Mali. Like the proverbial bad penny, ag-Ghali turns up wherever a cash transaction between a foreign government and Kidal Tuaregs appears forthcoming.” This cable also speculates on Iyad’s various and ever-shifting alliances with other rebel leaders and power players in northern Mali.

Whatever his motives, Iyad was now firmly established in the role he’d prophesied for himself: a Tuareg leader shaping the future of his people and a force in Malian and Saharan politics. A further plot twist awaited him, though, in the late 1990s, one that continues to be debated and continues to have consequences for Mali and maybe for much of Northern Africa: Iyad either found himself on a path of deep religious conversion, or he gambled on strategic religious-political alliances, or a bit of both.

Though Muslim, Iyad (like many Tuareg and many Malians) was not particularly austere in his religious observance at that point and was known to enjoy his whiskey and cigarettes, which would seem fully in keeping with his well-deserved reputation as a fierce, hardened fighter and shrewd politician. A word about Tuareg and Malian Islam: at the risk of generalizing, Malian Islam has historically been Sufi, introduced in the 9th century by traders and scholars. Northern cities such as Gao and Timbuktu became, over the centuries, major centers of Sufi scholarship and learning. Without digressing into a diagnosis of Malian Sufi Islam as more or less “tolerant” than other forms of Islam, it should be noted that this is the longstanding practice and tradition into which Iyad was born—to a clan and tribe that traced its lineage to the Prophet himself, no less.

But all that may have changed for Iyad just prior to the turn of the millennium, when he reportedly met (or reached out to, as some say) a Pakistan-based evangelist group, the Tablighi Jama’at, in Mali. They encourage missionary work, preach a revivalist, non-violent theology (its leaders repeatedly disavow violent jihad) and advocate a commitment to shari’ah. In American terms, they might be best understood as evangelical, or in Keenan’s pithy turn of phrase, as “an Islamic version of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

Iyad’s apparent conversion to the Tablighi was surprising not only because of his fondness for whiskey but because of his heritage. As Keenan put it, “[The Taureg] don’t take kindly to having religion rammed down their throats.” Iyad’s apparent fervor even became the butt of jokes in the Kidal region among those who’d known him for years, according to Keenan, who refers to his longtime informants’ commentary: “At the time, there were an awful lot of jokes. ‘Where’s Iyad?,’ they’d ask… ‘Oh he’s saying his prayers – he’s not drinking his whiskey.’” Nevertheless, the BBC reported (though the assertion is not fully substantiated) that in 2002, Iyad spent time at a Tablighi Jama’at mosque near Paris, studying the Qur’an, a report that suggests his conversion was not necessarily simply one of material or social expediency.

Given his most recent, and very violent, return to northern Mali, and his newly expressed commitment to a much more violent, hardline version of Islam than either his native or the Tablighi one, the depth of Iyad’s religious commitment remains a critical question. It’s critical not only for those living in or fleeing from an Ansar-dominated northern Mali, but for any actors, locally or globally, who must engage with him. And it remains a puzzle. Thanks to Wikileaks, we know that in May, 2007, Iyad shared the following assessment of al-Qaeda-linked activity (specifically, what was by then being called AQIM, or Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb) in northern Mali with the American ambassador:

Ag-Ghali said one of AQIM’s weak points was that not many people in northern Mali buy into its extremist ideology. He said that… the northern Tuaregs had repeatedly asked AQIM (then known as the GSPC) to leave northern Mali… AQIM refused, arguing that the territory it occupied belonged to neither Mali, nor the ADC, nor the Tuareg people, but to God… Ag-Ghali estimated that AQIM had little to no support amongst the native populations of northern Mali, but that dislodging the group remained difficult… we need, he said, the Malian government to handle… AQIM. Ag-Ghali reported that Tuaregs were prepared to accept an expanded Malian military presence in the north. He also requested U.S. assistance for the new “special” units.

What happened to the Iyad who, in 2007, gave this sanguine assessment of al-Qaeda’s relevance to northern Malians, and sought assistance from both the government of Mali and the U.S. to get rid of them? Has he become more “exacting,” in the words of the epic? What happened—to Iyad and in northern Mali—over the last decade or so?

The short answer is: the U.S.-led Global War on Terror happened, the Americans opened military bases and operations across North Africa, invested in a whole new command structure (AFRICOM), and began spending money—a lot of money.[1] The post-9/11 “GWOT” context gave global implications to what had been local and regional struggles in the Sahara-Sahel region. To put the situation in “market-based” terms: one, probably unintended, consequence of the GWOT money directed at the region is that it has ratcheted up the stakes, and the money to be made, from all manner of trade, including smuggling, arms dealing, and kidnapping for both profit and “political” ends. The latter, especially, has unquestionably increased in the region over the past decade, and it’s well documented that Iyad was making money as a connected negotiator in hostage crises. An entrenched and lucrative “market” for such activities will always complicate conflict resolution and threatens to generate further instability. In turn, further instability calls out for further attention, and provides the opening for military actors like AFRICOM (and the Malian and neighboring armies, and international peacekeepers) to cement their own strategic importance as they compete for prominence and budget share in their own contexts. In other words, the terrorist threat of AQIM, al-Qaeda, MUJAO and Iyad’s Ansar-al-Din are the exactly the kinds of catalysts that now justify and seem to warrant international intervention – as reflected in the catchphrase metaphor of “Mali as the next Afghanistan.”

That short answer raises another question: how intimately connected is Iyad’s religious journey to these geopolitical developments?

Joe McKnight is an MA candidate at Union Theological Seminary, concentrating on psychiatry and religion. A graduate of the Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, he is working to integrate his writing on religion with his interest in foreign affairs in Africa as well as exploration of his Southern heritage.

Editing and additional research by Nora Connor.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.

[1] Sticking strictly to the American money that’s being spent in the region, to say nothing of that from other states, international groups and politically interested actors: AFRICOM reports that its annual “operations and maintenance” budget is around $300 million, but a recent analysis of FY2010 budget requests indicates that total yearly U.S. expenditures on AFRICOM (including funds, supplies, etc outside the defense budget from sources like the State Department or CIA) is more like $1 billion per year ($1.4 billion for 2010, pre-Arab spring. Anyone want to bet that we’re now spending less on military and security issues in Africa?) Source: