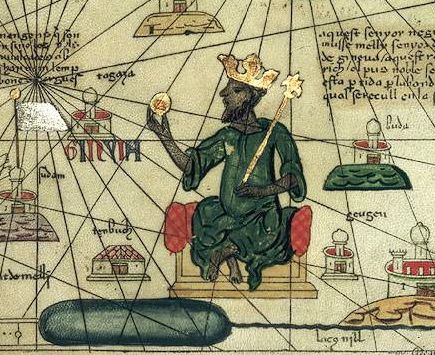

“My word is pure and free from all untruth; it is the word of my father; it is the word of my father’s father’s. When a quarrel breaks out between tribes it is we who settle the difference, for we are the depositaries of oaths which the ancestors swore…by my mouth you will learn the history of Mali. By my mouth you will get to know the story of the ancestor of great Mali, the story of him who, by his exploits, surpassed even Alexander the Great; he who, from the East, shed his rays upon all the countries of the West.”

–(A griot prepares to tell the 13th century tale of Sundiata, who would return from exile to unite and rule the Malian Empire). From Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali, D.T Niane, 1965 (as told to him by Mamadou Kouyate)

This post is the first in a series comparing the epic lives of Sundiata, medieval Malian ruler, and Iyad ag-Ghali, a power player and leader in Malian rebel movements for nearly forty years.

By Joe McKnight

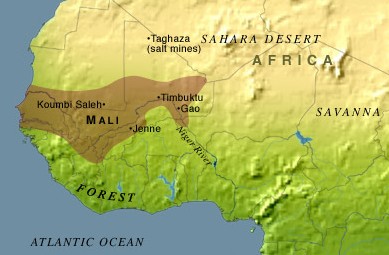

This summer’s destruction of ancient Sufi shrines in the Malian city of Timbuktu made the escalating conflict in northern Mali a top news story. International outrage ensued, with even the International Criminal Court’s Chief Prosecutor openly considering the possibility of war crimes charges. The desecration of the shrines also signaled shifts in the dynamics among all players in the crisis, including the southern-based national government (which, since April, has pretty much consisted of a military junta, an army in disarray and a constitutional crisis), as well as between various factions in northern Mali—a dizzying and fast-changing whirl of alliances and splits among an alphabet-soup of Tuareg rebels, separatists, Islamists and an assortment of actual and rumored foreign supporters. The seeming intractability of the situation has some analysts predicting that northern Mali could become the “Afghanistan of Africa.”

That sounds pretty bad. And things are pretty bad for people all over Mali right now, not just in the north, and nobody seems quite sure what, if any, outside intervention might prevent the situation from getting even worse, though it looks like international troops may soon be in Bamako. But before we panic about Afghanistan or quagmires, let’s take a look at a map and agree (h/t to Andrew Lebovich) that Mali isn’t Afghanistan, and let’s not end up burning down the village in order to save it. Here’s what we know, based on the average news account: extremist Islamist organizations are in control, or are at least heavily armed and forceful enough to cause horrific damage in a large part of northern Mali right now (the BBC reports that 430,000 have fled the north). Ansar Dine, the Islamist organization that perpetrated the destruction of the shrines, and now, apparently, another Islamist faction (MUJAO, or Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa), have moved on to even grimmer acts of violence like amputating peoples’ hands and execution by stoning. Both groups are linked with al-Qaeda, but the depth and nature of the connection (Financial? Ideological? Mutual convenience?) is still a question and may be changing as I write.

But somehow, all that doesn’t seem to clarify much. In my news-reading quest to understand what’s happening in Mali, one name kept repeating itself: Iyad ag-Ghali, leader of Ansar Dine. In the news, he appears as a vague and mysterious, but powerful figure. After looking a little deeper, it seems to me his story, and his political role, may be one that ends up profoundly altering the future of the former French colony. Reminiscent of a folk epic, the story of the present, tenuous ruler of at least parts of northern Mali is defined by transformation and survival. He’s a Tuareg, and therefore a nomad, but an elite one from a prominent tribe; a sometime exile; a fighter trained in Muammar Gaddfi’s Libyan camps; a mercenary for the PLO in 1980s Lebanon; an alleged agent for the Algerian secret police; a leader of the 1990 Tuareg Rebellion against the central government of Mali; advisor to the Malian consulate in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; a hostage negotiator for al-Qaeda, the Malian government and others; a convert (at least in name) to a radicalized Islam; and now, the figure at the center of a crisis that could well destabilize West Africa. This is the story of Iyad ag-Ghali: a story where fact and myth have become tangled and one that reads like a Malian epic of antiquity, but may very soon play out as tragedy.

“Shrouded in a haze of dust”

Iyad ag-Ghali is not an easy man to pin down. The historical, verifiable record of his life and movements is intriguing, but thin, and more suggestive than conclusive—a patchwork of the expertise of military analysts, anthropologists and historians who’ve spent decades in northern Mali and the Sahel-Sahara region, their informants’ accounts, informants’ accounts that complicate those accounts, a surprising number of Wikileaked U.S. embassy cables mentioning Iyad, and his recent statements to the press, few of which are readily available to the Western reader. As pre-eminent Sahara historian Baz Lecocq observes, “in following events in the Sahara, everything is shrouded in a haze of dust. Nothing is known with certainty, all depends on rumor and a form of hearsay known as the ‘Tuareg Telegraph.’” Lecocq goes on to advise prudence in analyzing news from the region. When I began investigating Iyad, my only real frame of reference to Mali was an African Lit course I took as an undergrad. Our professor was Nigerian and most of the reading was West African or diasporic. Our first book was Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali, the semi-historical folk tale of the great Malian warrior and ruler of the thirteenth century, which remains a foundational story for the Malian nation. Although Sundiata (soon-jah-ta) hailed from what is today southern Mali and Iyad was born in the north, their narratives of suffering, exile, return and re-conquest make for a provocative comparison.

For generations, the legend of Sundiata was kept orally (it was eventually written and published, but not until 1965), and told by the West African storytellers called griots, whose roles are somewhat analagous to those of a bard. As the source and repository of communal history, the griot was raised and trained in a family vocation, tasked with the teaching and preservation of a millennia’s worth of knowledge–tribal lineages, political history, stories. And the primary responsibility of the griot was toward the king or leader. According to historian James Jones in the introduction to the epic, “the griot served a ruler in much the same way that modern rulers are served by written constitutions, legal staff and archival staffs. Griots recalled what earlier leaders had done to advise current leaders on how to handle problems.” As the son of a king, Sundiata himself would have been assigned a personal griot at an early age. In Sundiata, the eponymous royal child was destined by prophecy to be a great ruler. Born a cripple, he teaches himself to walk, is persecuted by rivals, exiled, and returns as a valiant fighter, a conquering hero and unifying leader who brings peace to his land.

Overlay map showing the region of colonial French Sudan over current national boundaries. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the boundaries and politics of Sundiata’s Great Mali had changed dramatically. The story of Iyad is in many ways the story of modern Mali. By 1900, Mali was under the colonial thumb of the French, who had expanded what was called the French Sudan deep into the Sahara desert. The French made Bamako, in Mali’s southeast, the capital of French Sudan, and the vast majority of political activity, education and military power were concentrated in the south. Southern Mali was and continues to be populated by a majority of ethnically black Africans, but both southern Malians and northern Tuareg Malians are mostly Muslim, and all of Mali includes other complex ethnic and religious affiliations, including Arabs. Those in Northern French Sudan, a land historically central to the various nomadic Tuareg tribes, found themselves crushed under the weight of the colonial administration’s economic policies and new political boundaries, peripheral to the action and with no real purchase on the political and economic overhaul of their lives. Barbara Worley, professor of anthropology at the University of Massachusetts, described to me the lasting impacts of the French colonial system on the Tuareg in northern Mali—maybe most importantly, the imposition of state borders on a nomadic pastoralist people:

France totally broke down the Tuareg economic system based on nomadic pastoralism and trade…They made [new] boundaries, which never existed before. The Tuareg had been able to move their herds, especially in times of drought. Suddenly, [they] were trapped and couldn’t get their herds to water…and the trans-Saharan caravan trade was a major source of income for the Tuareg. The French [took over] the caravan trade, effectively destroying pastoral nomadism.

In 1960, shortly before Sundiata’s written publication, the French Sudan achieved independence. The new nation: the Republic of Mali. Yet the colonial-era centralization of power and resources in Bamako had taken root, and the political and economic divide between southern and northern Mali remained. It’s a bit of irony for my comparison between the two mens’ journeys, that in forging a new national identity, the Malian state invoked the glory of the Great Malian Empire, and legends like Sundiata’s. These themes would have been at best meaningless, if not an actual provocation, to the northern Tuaregs like Iyad’s elders, who were fully aware that the new political class viewed them as a potential threat and as “backward nomads” in need of modernization (read: sedentarization). In 1962, the First Tuareg Rebellion broke out—the initial eruption of a lasting movement towards an independent Tuareg state, or, depending on whom and when you asked, towards greater autonomy and a greater share of resources for the north. This rebellion evidenced a deep distrust on the part of northerners towards the new Malian central government. It also set Iyad ag-Ghali’s extraordinary life on its way.

Joe McKnight is an MA candidate at Union Theological Seminary, concentrating on psychiatry and religion. A graduate of the Grady School of Journalism at the University of Georgia, he is working to integrate his writing on religion with his interest in foreign affairs in Africa as well as exploration of his Southern heritage.

Editing and additional research by Nora Connor.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.