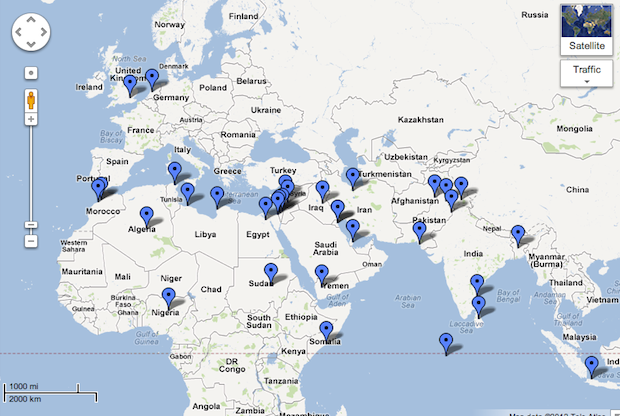

A recent Google Maps image tracking locations where demonstrations against the “Muslim Innocence” video have occurred.

by Alex Thurston

The international media has devoted much attention to Muslim protests against an anti-Islamic film in Egypt and Libya, where American Ambassador Chris Stevens was killed in the line of duty on September 11th. Protests against the film have taken on a global scope, including protests in sub-Saharan Africa. These African protests highlight the broad range of attitudes the global Muslim community is evincing during this episode. African responses have ranged from violent protests to calls for peace.

In Sudan, demonstrations rivaled those of Egypt in intensity. On September 14, Reuters reported, protesters “broke into the U.S. and German embassy compounds in Khartoum and raised Islamic flags.” Reuters added that the protests, even though they injured dozens of policemen, had received some backing from an official council of Islamic scholars. Sudanese politicians have spoken out against the film directly; for example, the official SUNA news agency (Arabic) reports that Governor Uthman Muhammad Yusuf Kabara of North Darfur “stressed that the vicious attack to which Islam and Muslims have been subjected by the Zionist and Jewish lobby and the Western agencies that side with them…will only increase Muslims’ unity and cohesion.” Reuters suggests that Sudanese President Omar al Bashir has tolerated protests against the film as a nod to the country’s Islamists, a significant political force. Yet by Friday the 21st, the Sudanese government was beginning to deny activists permission to stage demonstrations, perhaps fearing an escalation of violence.

In Nigeria, religious and political authorities have moved to calm, rather than stoke, tempers. Nigeria has seen a range of activity, including public protests. In Kaduna, authorities initially banned protests, fearing that they might trigger another of the city’s waves of interreligious violence, but a nonviolent demonstration eventually went forward on September 24. A march in Sokoto also proceeded peacefully. In Jos, a flashpoint for Muslim-Christian conflict, security forces “fired into the air on [September 14] to disperse” a peaceful Muslim protest, fearing that it might spark renewed conflict in the city. The Imam of Jos’s Central Mosque condemned the film but urged restraint and warned of the potential for chaos. The leader of Nigeria’s Society for the Removal of Heresy (known as Izala), a prominent Salafi organization, also discouraged violent responses to the film.

A demonstration in Kano, northern Nigeria, on September 22nd, proceeded peacefully. Photo: AFP/Aminu Abubakar.

Neighboring Niger has seen some violence connected to the film. On September 14, “hundreds of protesters stormed the cathedral in Niger’s second city of Zinder after Friday prayers, and set fire to US and British flags.” Yet religious authorities in Niger have tried to ensure that activism against the film would be peaceful. The country’s Islamic Council “condemned the US-made film…but also appealed for churches to be spared.” On September 16, an official from the Council gave a televised speech where he reiterated the group’s denunciation of the film “but urged Muslims to respond with ‘appeasement and tolerance, the cardinal virtues of Islam.’”

In other African Muslim countries, responses to the film have come in the press, and not necessarily in the streets. In some cases the film has prompted complex debates about how Muslims and non-Muslims should react. A Senegalese writer states (French), “Nothing justifies violence and the death of innocents…Regarding this blasphemy toward Islam, the reaction should not be violent but mystical and spiritual.” The author doesn’t absolve American authorities of blame, however, writing, “The Islamic world reproaches them for not having reacted properly…If one is capable of preventing the posting of child pornography, one should be able to block this stupidity.”

During episodes of Muslim protests against perceived Western blasphemy and ridicule, one often hears non-Muslims asking, “Where are the moderate Muslims?” Sometimes the question is disingenuous, and the questioner’s interest lies not in discovering an answer, but in implying that there are no moderate Muslims. Those asking the question in earnest, however, can look for answers to sub-Saharan Africa, where there have been instances of violence, but also authorities laboring for peace, and thinkers attempting to generate nuanced debate.

Alex Thurston is a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Northwestern University. For 2011-2012, he is conducting dissertation fieldwork in Northern Nigeria. Alex has written for the Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, and The Guardian. He blogs at http://sahelblog.wordpress.com, and is a regular contributor to The Revealer.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.