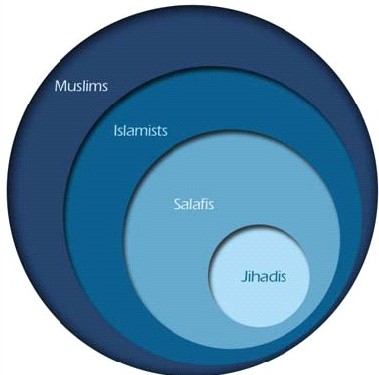

Aha! This diagram, attributed to the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point’s “Militant Ideology Atlas,” tidily summarizes the relationship between Muslims, Islamists, Salafis and Jihadis.

by Alex Thurston

The word “Salafism” is on many reporters’ and analysts’ tongues these days. In post-uprising Egypt and Tunisia, Salafi parties – Egypt’s Nour (Light) and Tunisia’s Islah (Reform) – have garnered significant attention, especially as observers parse relationships between Salafis and “Islamists,” represented by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood (which established the Freedom and Justice Party) and Tunisia’s Nahda (Awakening). In a much different context, violent Muslim movements in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere, such as Nigeria’s Boko Haram or Mali’s Ansar al Din, are labeled “salafi-jihadi” by some analysts. Suddenly, Salafism seems to be everywhere: mainstream Salafism, political Salafism, Wahhabist Salafism, Arab Salafism, Islamist Salafism, radical Salafism, and at least one instance of salafist-fundamentalist cage-fighting-ism.

This post is the first in a series attempting to disrupt several recurring tropes in the media concerning who Salafis are and what they want. This installment looks at definitions of Salafism and questions of political identity, especially as they concern electoral politics. There have been two interrelated problems in media coverage of Salafis’ relationships with politics, especially in the post-Arab spring Middle East. The first is categorizations that too rigidly differentiate Salafis from Islamists. The second is analysis that too rigidly demarcates the boundaries of “politics.”

Salafism: Definitions

Defining Salafism is tricky. The Arabic salaf means “ancestors” or “forefathers,” a reference to the Prophet Muhammad, his Companions, and the succeeding two generations of Muslims. To say that Salafis today look to these generations as models for conduct and worship is true but insufficient, since other Muslims also define themselves in relation to the early Muslim community. In Northern Nigeria, where I did fieldwork in 2011-2012, some Salafis refer to themselves as Ahl al Sunnah wa al Jama’a (Arabic: “The People of the Prophetic Model and the Muslim Community.”) But this phrase can refer to the Muslim community as a whole. One young Sufi leader (Sufis are sometimes condemned as heterodox by Salafis) told me that he felt the Salafis’ appropriation of this phrase was improper.

A tighter definition of Salafism, then, would include reference to how Salafis invoke the model of the early community. Salafism relies on a particular methodology that demands any Muslim practice must be legitimated by a proof-text, i.e. by a text from the Qur’an or from the Sunnah (as represented in individual hadith reports). Other Muslims also rely on proof-texts, but Salafi methodology is distinctive in its skepticism toward esotericism, its strict understanding of monotheism, and its willingness to reject and question the personal authority of later Muslim leaders (including Sufi sheikhs but also, in some cases, legal thinkers within the four major schools of Sunni Islam – some Salafis, unlike the majority of the world’s Muslims, do not adhere to any formal legal school). An even more rigorous definition, however, would note that Salafis do often recognize intellectual authorities beyond the early Muslim community. In historical terms, then, we can speak of a Salafi intellectual and activist tradition that includes Sheikhs Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855), Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al Wahhab (d. 1792), and more contemporary thinkers like Sheikh Nasir al Din al Albani (d. 1999).

These definitions are incomplete, and they address an ideal, not a living reality. When it comes to understanding how Salafis today interact with politics, the situation is even more complex.

Salafism and Politics

Dr. Jonathan Brown’s writing on Egypt (.pdf, p. 5) has demonstrated why it is a mistake to treat “Salafis” and “Islamists” as two completely distinct camps:

It is difficult to draw a clear line between Salafis and other religiously inclined Egyptian Muslims. Many Egyptians who listen to Salafi lectures in their cars or who watch Salafi satellite channels at home do not sport the Salafi long beard or wear distinctive clothing. They are average Egyptians whose religious temperament draws them to Salafi teachings…There is also no clear line of distinction between Salafis and the membership of the Muslim Brotherhood. The two groups share important teachings and an appreciable number of adherents. The Brotherhood emerged from the same reformist wave as modern Salafism, rejecting the byzantine complexities of Islamic law and theology as well as the superstitions of popular Sufism. While the Brotherhood took the path of modernized social and political activism, however, the vast majority of Salafis adhered to a traditional focus on honing belief and ritual practice.

Just because there are parties labeled “Salafi” and “Islamist” in the formal political arena, in other words, does not mean that strict lines between the two groups can be mapped onto entire societies.

As the lines between Salafis and Islamists become blurry outside of the realm of electoral politics, so too does the notion of “politics” itself. We hear frequently in media coverage that Salafis have now decided to “enter politics” after a long period of being politically quietist. That assertion is only sustainable if “politics” is limited to electoral competition. If, in contrast, we understand politics as a struggle for power and influence, a debate over individual and group identity, and a set of relationships between groups attempting to advance different programs for society, then Salafis have long been implicated in politics, sometimes against their will.

Consider Dr. Stéphane Lacroix’s remarks (.pdf, p. 2) on the origins of Egypt’s Nour Party:

The Nour Party was founded by an informal religious organization called the “Salafi Da‘wa” (alDa‘wa al-Salafiyya), whose leadership is based in Alexandria. The origins of the Salafi Da‘wa date back to the late 1970s, when its founders – students at the faculty of medicine at Alexandria University – broke away from the Islamist student groups known as al-Gama‘at al-Islamiyya (“Islamic groups”). Among them was Yasir Burhami, currently the dominant figure in the organization. The Salafi Da‘wa’s stance against violence and refusal to engage in formal politics made it relatively acceptable to the Mubarak regime. To be sure, the group did at times endure repression; its leaders were kept under close surveillance and were forbidden from traveling outside Alexandria. However, the Salafi Da‘wa often benefited from the covert support of the regime apparatus, which tried to use Salafis to undermine the Muslim Brotherhood’s influence.

Here we have several forms of politics: factionalization within Muslim associations, and multiple relationships between Salafis and the regime (surveillance, support, and repression). To push the argument even further, even stances against violence and against “formal politics” represent political choices. Politics is hard to avoid.

Strict separations between formal and informal politics are also not always tenable. One of my dissertation chapters concerns Salafis’ struggles for control of a Friday mosque in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Neighborhood-level disputes over a mosque may constitute “informal” politics, but the dispute soon drew in the city’s traditional leaders and the state’s elected governor, Ibrahim Shekarau. Shekarau faced re-election in 2007 while the controversy over the mosque was still raging. Some Salafi leaders even began to mobilize against him in the electoral arena. This incident demonstrates how futile it is to separate ‘formal’ from ‘informal’ politics.

I do not want to minimize the significance of Egyptian and Tunisian Salafis’ decisions to form political parties and contest elections. But if we base our understanding of Salafism today on bounded political entities and narrow assumptions about what politics is, we miss much of the complexity of Salafism (including as a political force) and much of the complexity of how struggles over Muslim identity are playing out in communities around the world.

Alex Thurston is a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Northwestern University. For 2011-2012, he is conducting dissertation fieldwork in Northern Nigeria. Alex has written for the Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, and The Guardian. He blogs at http://sahelblog.wordpress.com, and is a regular contributor to The Revealer.