by Amy Levin:

Ever since Madonna and Tom Cruise carried the banner for Kabbalah and Scientology, respectively, New Religious Movements began frequenting the proverbial red carpet in religion news coverage more than ever before. Easy to digest with their suave techy aesthetics, simple truths and practical wisdoms, and liberal-inspired universality, New Religious Movements (NRMs) seem to evoke a polarity of responses, ranging from conspiracy-backed skepticism from their critics and eager optimism for self-betterment in their followers. These prisms shed a limited degree of light on the ways NRMs operate, and hence, I’ve decided to do my best to dodge these easy interpretations as the newest NRM scandal creeps in. The latest headline? Try this juicy read from the Associated Press published just last week: “Contentious Religion from Japan Succeeds in Uganda.”

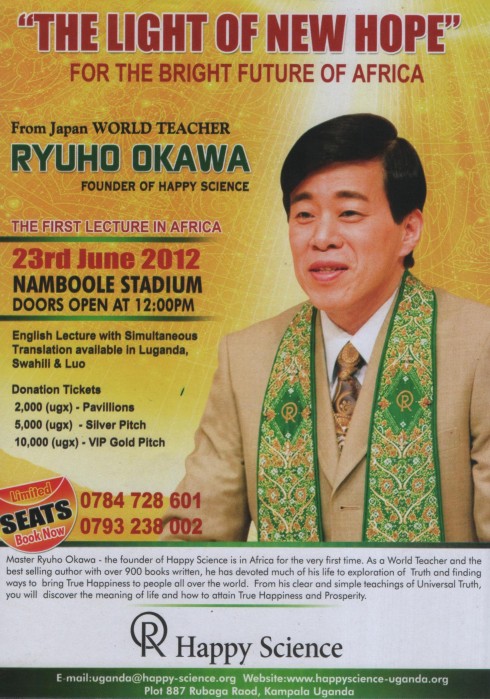

It’s called “Happy Science,” self-described as a “worldwide movement for the happiness of humanity.” My first inclination is to ask why only Uganda is behind a gospel of happiness – I know I am. According to Rodney Muhumaza’s widely circulated AP article – perhaps the only existing in-depth report on the current controversy – Happy Science is a Japanese-born religious movement whose success in Uganda recently “attracted the attention of Christian clerics offended by its beliefs.” This new attention is presumably due to the visit from the movement’s founder and leader, Ryuho Okawa, whose lecture inside the national stadium welcomed over 10,000 attendees, “causing traffic jams and upsetting athletes who had planned to use the space for Olympic trials.” Okawa’s visit was his first to Africa, but Happy Science officials transported their teachings to Uganda in 2008, reflecting their hope to, according to Muhumaza, “use the East African country as a springboard for what they hope will be success across Africa.”

Two Kampala Pentecostal pastors were recently featured on “Urban TV,” one of Kampala’s news channels, branding Happy Science as a cult. The news segment aired just days before Okawa’s visit and featured a number of concerned clergy members skeptical of Okawa’s motives. Pastor Martin Ssempa of Makerere Community Church, notorious for his anti-gay activism, specifically condemned Okawa’s claim to divine status. According to Ssempa, “[Okawa] has said that he’s El Cantare. El Cantare, according to him, is the Lord God of the heavens and the earth; a combination of Buddha, a combination of the God of Jesus, and a combination of the God of Muhammad.” Ssempa denounced what he said was Okawa’s claim to possess the spirits of living individuals, including “Romney and Obama.” However, given Ssempa’s practice of charismatic Christianity, his skepticism may not be against the idea of being spirit-filled, but more a matter of impersonating God: “. . .when Jesus warned us, he warned us to check out people like this man Okawa, who is claiming that he is God, and such is a lie and a blasphemy. It is blasphemous for a man to claim to be God.”

The concerned clergy members claim that Happy Science’s success is due to Happy Science’s involvement with material relief work–almost like an aid NGO–and the promise of happiness so overtly embedded in the name. Indeed, the local branch, headed by Tomohiko Nakagawa, has already provided tuition fees, school materials, and mosquito nets to residents of Kampala and its surrounding villages. As for the promise of happiness, Happy Science’s branch manager of South Africa, Brian Rycroft, captures it best in his TV interview: “[Happy Science] can help people to overcome illness, get over poverty, have better relationships and overcome conflict, and create a peaceful world.” Rycroft of course does not say whether or not these benefits are achieved through the movement’s material or spiritual offerings – but we can only imagine what kind of psychological labor a science of happiness performs (think Prosperity Gospel + Christian Science’s mind over matter beliefs).

The sudden (visible) global interest in Happy Science is at least in part due to its controversial missionary endeavors—and probably the fact that it seems to be having some success. Now that the pastors have spilled the linguistic blood on Happy Science, calling it the “C” word, the questions many of us can’t help but ask is, well, is it a cult? Are their motives genuine/ethical/truthful? Is Okawa a scam? The answers don’t seem encouraging. For one, take Okawa’s career trajectory. Okawa’s followers do their best to wax his change of path as a rebirth narrative – indeed, Okawa’s pre-Happy Science days sound anything-but-devout. After he studied law at the University of Tokyo, Okawa took a job at a major trading company and was soon transferred to the New York Headquarters in their International Finance Division. During his employment, Okawa completed his degree in international finance study at the Graduate School at the City University of New York. Immediately following his promotion, Okawa resigned from the company and began Happy Science in 1986. Want more Happy trivia? Brian Rycroft worked as a tax consultant for Ernst and Young before becoming branch manager of Happy Science’s South Africa division (thanks Linkedin).

Okawa and Rycroft’s trajectory practically screams business strategy. But let’s prolong investigative gratification for the time being. For one, would it make a difference if we heard Okawa speak about the meaninglessness of his overly-worked corporate days as a catalyst to bring this spiritual Truth to people, as Happy Science so platitudinously promises? Why is it that some conversion narratives tug at our hearts and others at our . . .rational neocortex? Furthermore, why is it that the Newer-Agey propagators like Okawa and Rycroft are scammers while the recently converted Happy Science-ers are agentless dupes (collective effervescence)? In other words, what opportunities for knowledge are we overlooking when we read missionizing solely as a neocolonial abuse of power? While I have little to offer here ethnographically (besides this quite obscure video of Happy Science services in Uganda), let’s not forget that Okawa was hardly the first to spread his gospel to locations in need of serious relief, aka, the global south.

As a New Religious Movement, Happy Science shares much in common with its strange bedfellows. NRMs ranging from the LDS Church to the Kabbalah Centre to the Church of Scientology proselytize in countries with particularly high poverty rates – countries that are no stranger to missions. In Uganda, the demographic breakdown of religious affiliation is 41.9 percent Roman Catholic, 42 percent Protestant, 12.1 percent Muslim, 3.1 percent other, and 0.9% no religion. The question is, given Uganda’s missionary history, are NRMs like Happy Science threatening because of their presumed theological abnormalities (“un-Christian,” “cultish”) or because of their postcolonial legacy?

Without losing sight of the still-evolving repercussions of colonial and missionary history, we might do well to unleash some of the liberating or socially alternative potentialities that NRMs offer in postcolonial countries. The politics wrapped up in conversion for those Ugandans who are embracing Happy Science is undoubtedly more complicated than we presume. What does it really mean to join such a religion? What does being Happy Scientist entail? The epistemic danger here is that the gospel of happiness seems to posit freedom vis-a-vis the embrace of a single belief system. But ethnographic scholarship on missionary history proves that converts have an emotionally mixed relationship to missionary efforts. For many individuals who receive material benefits in countries stricken by extreme poverty, that embrace/performance of “conversion” often serves as more of a means to an end (quality of life) than the end (religion) itself. Thus, receiving the gospel, whether it be in the form of the New Testament or Happy Science, is never just about money, and never just about religion.

Regardless of Okawa’s motives, the manner in which his gospel is taken up and lived out is an entirely undetermined process. The ways in which individuals in the past appropriated their indigenous religious beliefs with Christianity, for instance, created new ways of being religious altogether. As we continue to scrutinize and (rightly) question the marketization of Okawa’s one million books sold, I at least hope we offer some credit to his followers. In homage to that religion we call science, if there is indeed a science of happiness, we would do well to check the results before we throw out the method.