by David Halperin

1.

Have a taste for real-life mystery? Forget the Bermuda Triangle; it’s stale, it’s banal. Give your mind instead to the richer, more perplexing enigma I call the Philadelphia triangle.

I don’t mean “triangle” geographically. I’m speaking of three men out of whose triangular interactions emerged one of the stranger and more enduring legends—shall we even call it a myth?—of our time. Namely, that sometime during World War II an experiment was performed in the Philadelphia Navy Yard that resulted in a ship’s being turned invisible, then teleported to Norfolk, Virginia, and back again, with horrific consequences for those unfortunate souls on board.

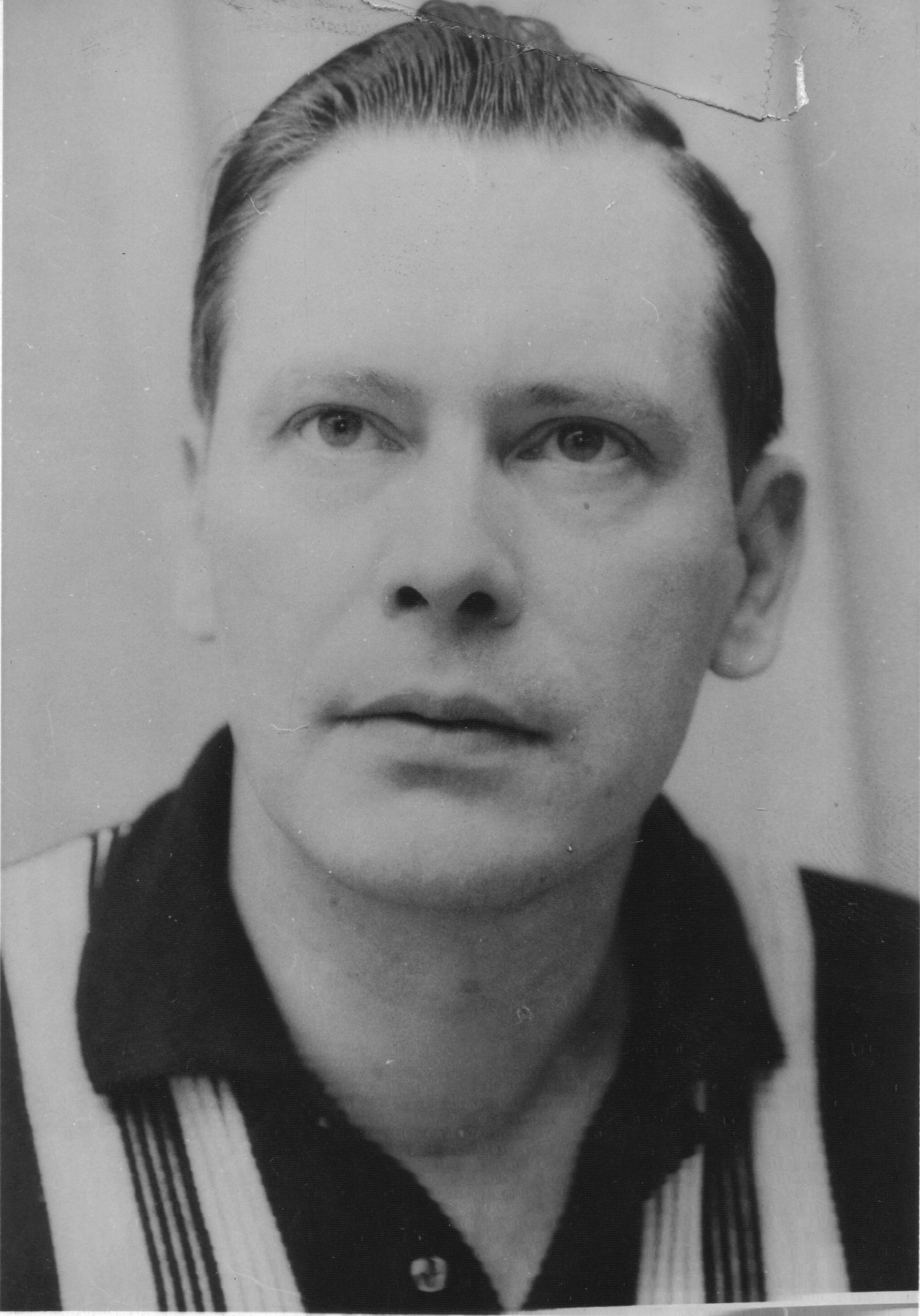

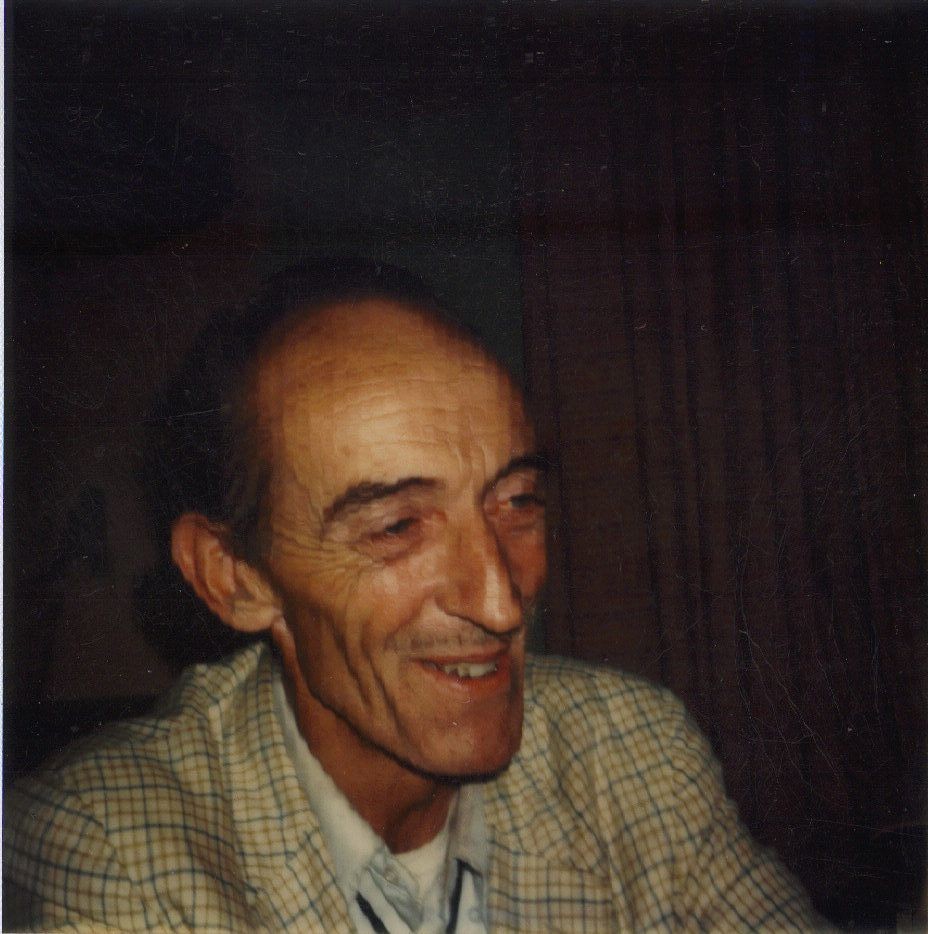

The three corners of this human triangle were Morris Ketchum Jessup (1900-1959), Gray Barker (1925-1984), and Carl M. Allen a.k.a. Carlos Allende (1925-1994). All three were extraordinary, in ways that did hardly a speck of good for any of them. All came to bad ends. Jessup committed suicide. Barker died of AIDS. Allende breathed his last, impoverished and alone, in a Colorado nursing home.

The myth they created fared better. It begot at least one novel (not counting my own), a non-fiction best-seller, and two movies (“The Philadelphia Experiment,” 1984; “Philadelphia Experiment II,” 1993). Cultural references to it are legion. The phrase “Philadelphia experiment” currently gets upwards of 60,000 Google searches each month.

How did this happen? What does it mean?

2.

In September 2004, I spent the better part of a week at the Gray Barker Collection of the Clarksburg-Harrison Public Library (Clarksburg, WV), rummaging through the files left behind by this mythmaker extraordinaire. I’d prepared for my visit with a phone conversation with David Houchin, genial curator of the collection. They had a file of correspondence between Barker and Morris Jessup, David told me; and I was delighted to hear that. There were also files of letters from a man named Carl Allen, and this bit of information nearly floored me. The Carl Allen? Naively, I imagined Allen to be the taciturn, elusive mystery man he was portrayed as in the 1960s UFOlogy I knew so well.

Gray Barker is already familiar to those who’ve read my Revealer essays. Morris K. Jessup was a different sort of person altogether. If Barker’s roots were in hardscrabble West Virginia poverty, Jessup was a Midwesterner, of a family described as “shabby-genteel.” If Barker remained all his life true to his name (with “carnival” prefixed) Jessup was ever the scientist manqué.

He was a “brain,” one of his high school classmates remembered, for whom “a brilliant future” was predicted. He went to college at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he first majored and then did graduate work in astronomy. There his promise soured. The one-time teachers’ pet had turned snarly, rambunctious. A professor recalled his “outbursts of temper that verged on the insane.” He never completed his dissertation, and “left Ann Arbor in the summer of 1931 with extremely bitter feeling toward the university and the department of astronomy.” Academic science had failed him. He would create a science that would transcend it, render it obsolete.

His first book, The Case for the UFO, appeared in 1955. He followed it two years later with The Expanding Case for the UFO. In these books he brought his fascination with the moon, with ethnology and pre-Columbian archaeology, with freaks of weather and bizarre disappearances, into brilliant if uncritical synthesis. He saw the UFOs as coming from a point of gravitation neutral between earth and moon, intertwined with human history since its dawning, the esoteric shadow of that history. Gray Barker learned of his work and was impressed. The two men struck up a correspondence, then a friendship.

Jessup, 25 years Barker’s senior, appears in their exchanges as an elder statesman, mentoring Barker in the ways of the publishing world. He breaks the news to the younger man that “the publishing industry is run for the benifit [sic] of the publishing industry, and not for the writers.” Of course he cares about the money; who doesn’t? But he’s also genuinely devoted to the science he pioneers. “I do feel that we are in a remarkable phase of human experience and that the waters should not be muddied by stupidity.” Personal affairs merit only incidental mention. “Must warn you,” he writes in parentheses, “I’ve been divorced & remarried since I saw you.” Perhaps oddly, perhaps not, he never mentions to Barker the letters he’d begun receiving from a man calling himself variously “Carlos Miguel Allende” and “Carl M. Allen.”

3.

The first letter was sent at the beginning of 1956, from New Kensington, Pennsylvania, and it told a strange story in even stranger syntax, with capitalization and punctuation to match. The tale was of a secret Navy experiment that resulted in “the complete invisibility of a ship, Destroyer type, and all of its crew, While at Sea (Oct. 1943).”

Half of the officiers [sic] & the crew of that Ship are at Present, Mad as Hatters. A few, are even Yet confined to certain areas where they May receive trained Scientific aid when they, either, “Go Blank” or “Go Blank” & Get Stuck.” … The Man thusly stricken can Not Move of his own volition unless two or More of those who are within the field go & touch him, quickly, else he “Freezes”. … If around or Near the Philadelphia Navy Yard you see a group of Sailors in the act of Putting their Hands upon a fellor [sic] or upon “thin air”, observe the Digits & appendages of the Stricken Man. If they seem to Waver, as tho within a Heat-Mirage, go quickly & put YOUR Hands upon Him, For that Man is The Very most Desperate of Men in The World.

After describing the terrifying, paradoxical experience of simultaneously freezing and going into “The Flame” (“THEY BURNED FOR 18 DAYS”), Allende offers a terse summary: “The expieriment [sic] Was a Complete Success. The Men were Complete Failures.”

The USS Eldridge

Excitedly Jessup wrote back, asking for more information. At the end of May he received another letter. Allende begged that he and other witnesses be put under hypnosis or administered “truth serum,” so they could fully recall what they had seen. It’s usually assumed that Allende claimed to have watched the experiment from the deck of a nearby ship. Yet this point never emerges clearly from his initial letters; for the most part, we’re left to guess how he knows the things he does. His style is the omniscience of myth: not “I saw” but “it was.”

The correspondence died out. Not long afterward Jessup was contacted by the Office of Naval Research in Washington, DC. Seems they’d been sent a paperback copy of his Case for the UFO, annotated in three different handwritings, using three colors of ink. By three men engaged in intense dialogue on the subject of Jessup’s book. Three men who seemed to know an awful lot about things which for Jessup had been objects of speculation.

Jessup instantly identified one of the writers as Carlos Allende.

Only one of the three is actually named in the annotations. The others call him “Jemi,” address him as “my twin”; surely there’s some connection with “Gemini.” (Especially since, as Robert Goerman has pointed out, Gemini was Carl Allen’s birth sign.) Back and forth the three men write, judging how well or poorly Jessup has guessed at the truth, tossing out cryptic hints at a ramified mythology of which the Philadelphia experiment was only the iceberg’s tip. Alien races appear, battling among themselves, asteroids as their weapons. So does a “Great Ark,” a sort of primordial mother-ship. The writers represent themselves as an esoteric fraternity of gypsies. “Fortunately for Mankinds ego only a Gypsy will tell another of that Catastrophe [sc. “the Great War of the ancients”]. and we are a descredited peopole [sic], ages ago.”

The Navy officers were intrigued. Possibly it was the “gypsies’ ” rhetoric—oracular, incantatory, apocalyptic, to borrow Joseph Mitchell’s words—that held them in thrall. At Lord knows how much trouble and expense, they engaged the Varo Manufacturing Company of Garland, Texas, to prepare a mimeographed edition, with Jessup’s text and the annotations in different colored inks. Some two dozen copies were run off. Jessup received one; shortly before his death he handed it on to one of his closest friends. Another was offered to Carl Allen by an executive of the Varo Company. In his letter, the executive addresses Allen in a tone of respect bordering on reverence. “It would indeed be a pleasure,” he writes, “to meet you and to discuss some of the implications of the book. As I travel a great deal all over the U.S.A., it would be convenient to meet you at almost any point.”

Apparently the meeting never took place; Allen still had the wisdom to stay coy and aloof. He was at the zenith of his career, such as it was. Jessup, meanwhile, hurtled toward his nadir. His new wife left him; his manuscripts went begging for a publisher. At about 6:00 p.m. on April 20, 1959, he parked his car in Matheson Hammock Park in Coral Gables, Florida. He ran a piece of rubber tubing from the exhaust pipe into the car, closed the windows, started the engine. Two hours later he was declared dead of carbon monoxide poisoning.

4.

Was Carl Allen really a gypsy?

Ethnically, no. Robert Goerman, a long-time neighbor of the Allens in their home town of New Kensington, knew the family to be half English, half French. But if “gypsy” means “wanderer,” that’s exactly what Carl Allen was.

First in the Coast Guard, where he served from October 1943 to September 1947. Discharged, he kept up his wandering. In the summer of 1954, when the Veterans Claims Division “reconsidered”—and discontinued—his disability pension, they sent him the news c/o the United States Consul, Guadalajara, Mexico. The dozens of letters from him in the Barker Collection, from 1977 onward, are a confusing blur of postmarks and return addresses. Arizona, Mexico … New Mexico, South Dakota, Nebraska … at last Colorado, where in 1994 he reached the end of his road.

His ambition once was to be “a Spanish-Gypsy guitarist.” So he wrote in 1985 to “Peggy,” a psychiatry resident in the Denver Veterans Administration hospital on whom he’d developed a humongous crush. Destiny decreed otherwise. He became instead a scientist, studying physics (he managed to convince himself) with Albert Einstein and George Gamow.

Not a whole lot of it, to be sure. An astronomy professor who met Allen in 1980 (and afterward wished he hadn’t) pegged him accurately as “a sad, frustrated old man who … knows no physics beyond a bit of jargon.” But if Allen wasn’t quite the “world-reknowned [sic] man of science” he wanted pretty Peggy to believe he was, it wasn’t for lack of aptitude. His younger brother remembered how Carl avoided school whenever he could, slept through classes when he couldn’t. “But if the teacher had a difficult algebra or calculus problem that needed solving, he’d wake Carl up and Carl would stare at it for a minute, recite the correct answer and go back to sleep.” A formidable talent, blasted almost from its birth, lay within this man. In this respect, as perhaps in others, he and Jessup were brothers under the skin.

5.

“Did Jessup also ‘know too much’???????????” This question is posed—yes, with eleven question marks—in Gray Barker’s forgettable The Strange Case of Dr. M.K. Jessup, published by Barker’s “Saucerian Press” four years after Jessup’s death. The sound you hear as you turn its pages is the bottom of the barrel being scraped. Alive, Morris Jessup was a friend, a respected colleague. Dead, he and his “Allende letters” were a potential cash cow, his supposedly “mysterious” demise one more theme for ooky-spooky speculation. (“It’s sort of like, after they’re dead you can eat them,” says David Houchin.)

Barker tried to find Allende. He tried to find a copy of the by now far-famed, all but unobtainable “Varo edition,” with an eye to doing a reprint. Eventually he got both his wishes. In 1973, Saucerian Press issued a facsimile edition of the “gypsy”-annotated Case for the UFO. In July 1977, Barker’s friend Jim Moseley managed to track Allende down in Prescott, Arizona. One month later the mystery man was in Clarksburg, on Barker’s dime, to tape an interview soon made available (by Saucerian Press) for purchase under the title “Carlos Allende Speaks.”

Barker and Moseley were in theory co-interviewers. But on the tape Moseley never speaks, while Barker keeps apologizing for something, it’s never clear just what. The explanation is in the subsequent correspondence: Barker and Moseley had prepared for the momentous interview by getting drunk. If Barker ever took Carlos Allende seriously, he’d given that up well in advance of their meeting.

Allende rambles on the tape about how many copies were made of the Varo edition. He credits his annotations in The Case for the UFO with the establishment (in 1957-58) of the International Geophysical Year. He demonstrates, as he had in private for Moseley, the trick by which he simulated three different handwritings in those annotations. (For, as the reader will surely have guessed by this time, the “three gypsies” were all Carl Allen himself.) Never does he explain his motive—what it was that impelled him, like the deity of Genesis 18, to split himself from one into three. Most remarkably, he speaks English with a pronounced Spanish accent. If I hadn’t known Carl M. Allen was a Pennsylvanian born and bred, I never would have imagined him a native English speaker.

This was, as far as I know, the only time Barker and Allen ever met face to face. It was the start of their years-long, mostly one-sided correspondence. The Barker Collection folders are stuffed with “Allende letters”—at times plaintive, at times abusive, always desperate for attention. Barker’s sparse replies are amused, urbane. Under cover of elaborate courtesy he pokes fun at the hapless Allen. Yet in his peculiar Barkeresque way he cares about him. Contacted by Hollywood representatives regarding a proposed movie about the Philadelphia experiment, he tries to put them in touch with Allen. “I was hoping that you might be able to turn some greenbacks by acting as a paid consultant for them.” Barker’s primary concern in his saucerian enterprises was for Number One. Yet if a kindness might be done in the process for Number Two, or Three or Four, he didn’t let the chance slide.

Too bad nothing came of Barker’s idea. I don’t know how many greenbacks the “Philadelphia Experiment” movie turned when it came out in 1984, but I imagine the number was considerable. The man who’d made the whole thing possible, meanwhile, was surviving on a meager Veterans Administration pension, “usually starving … except in summer when food is easily stolen.” He convinced himself he was suffering from sickle-cell anemia. He raged against the VA hospital administrators who, like the Federal bureaucrats who’d cut off his pension thirty years before, turned a blind eye to his pain.

Barker died in December 1984. Throughout the following year Allen kept on writing to him, no doubt wondering why his correspondent, never very forthcoming, had turned entirely mute. On December 22, 1985, he sent a logbook of the ship where he’d served as a teenager in the last months of 1943. “ ‘Destroyed by executive order’ this logbook … does not ‘officially’ exist.” The 37 witnesses, himself included, of the Philadelphia experiment had also been consigned to official non-existence. At the end he added a postscript: “P.S. Am very slowly dying.”

6.

Aren’t we all? Yet there’s something peculiarly poignant about this man’s fate. A gypsy who wasn’t a gypsy, a genius who could really have been the “world-reknowned” scientist he never was, Allen was one of the invisible men he wrote about with such demented eloquence.

“The Very most Desperate of Men in The World,” he called them; and he was right. The “expieriment” of post-war America was a complete success. Some at least of the men who’d made it possible were “Complete Failures.” Unseen; cast aside in the nation’s march to prosperity. Can it be coincidence (to ask the question beloved of conspiracy theorists) that it was precisely in the months after the refusal of his pension, in July 1954, that Allen created his myth of the experiment gone mad, its triumph built on the human wreckage left warped and crippled and hopeless?

Yet there was more than that to the Philadelphia experiment, and we must reckon with this if we’re to understand its abiding resonance. The myth spoke not only of invisibility but of transcendence, of instant transport over vast distances. It spoke these things to a nation bursting forth to space as its “new frontier.” True, it was first heard by those persuaded that outer space was already here in our skies, that we were the space people’s frontier no less than they were ours. But it didn’t remain with the UFOlogists; it was too protean for that, its echoes too powerful. It entered the cultural bloodstream. Half a century later, it remains.

“I am a star-gazer Mr. Jessup,” wrote Carlos Allende. “I make no bones about this and the fact that I feel that IF HANDLED PROPERLY, I.E.PRESENTED TO PEOPLE & SCIENCE IN THE PROPER PSYCHOLOGICALLY EFFECTIVE MANNER, I feel sure that man will go where He now dreams of being—to the stars.”

Maybe. But the stars are very distant; we’re very small. “Carl Allen, M.K. Jessup and Gray Barker,” I wrote in my diary one evening in Clarksburg, after a long day in the Barker archive. “What are these people but three pathetic losers, all of them thirsting to do great things, but without the capacity, position, or materials to do anything. Except create a mythology!

“And, in truth, are we not all pathetic losers, yearning for a significance that is beyond our grasp and that life itself may not offer? So these three may be, precisely in their failures, figures who have the power to teach us about our own yearnings and delusions, and to help us answer the ancient question: what is a human being?”

David Halperin is Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His novel Journal of a UFO Investigator, in which the Philadelphia Experiment is prominently featured, was published last year by Viking Press. It’s appeared in Spanish and Italian translations; a German edition is scheduled for August 2012. David blogs about UFOs, religion, and related subjects at www.davidhalperin.net. Visit his Fan Page at www.facebook.com/JournalofaUFOInvestigator.

Read additional articles by David Halperin here.