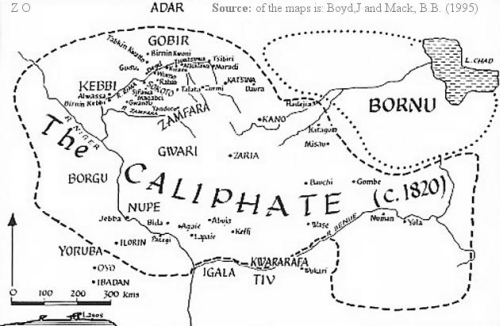

Rendering of the borders of the Sokoto Caliphate, present-day northern Nigeria, established by Uthman dan Fodio, still a revered scholar.

By Alex Thurston

This is the fifth post in a series on Islamic education in Northern Nigeria. The first post gave an overview of the series, the second discussed Qur’anic schools, the third talked about “traditional” advanced Islamic education, noting that traditions change over time, and the fourth post examined “Islamiyya” schools.

Nigeria has around 100 universities, most of them public, and many public and private colleges. Various tertiary institutions in Northern Nigeria offer Islamic Studies, sometimes conjoined with Arabic. Some academic centers specialize in one aspect of Islam. For example, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria hosts the Centre for Islamic Legal Studies, a think tank. That Centre helped codify shari’a law (.pdf) when it was re-implemented in Northern states after 1999.

During the period of my fieldwork earlier this academic year, my academic affiliation in Nigeria was to the Department of Islamic Studies at Bayero University Kano (BUK). The Department grants bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. At BUK, the Departments of Islamic Studies and Arabic are separate, although Arabic students often wrote their theses on Islamic themes, and some undergraduate students major in both subjects. Students in Islamic Studies, moreover, often write their theses in Arabic; if they prefer, they may write in English, though not in Hausa.

Neither BUK nor other major Northern universities are “Islamic Universities.” The Islamic Studies Departments there exist within secular universities, although as in many American universities religious language and themes frequently appear in events, student life (Nigeria has an influential, and nationwide, Muslim Students’ Society), and in the classroom.

The following excerpt from the Departmental website at BUK describes the Department’s mission:

All our courses are designed to expose students to Islam as a culture, religion and civilization. It aims at describing Islam as a complete way of life, using Islamic original sources. Serious efforts are made to maintain rigorous scholarly approach to the problems that confront the Muslim community in general and the Nigerian Muslims in particular.

At BUK, students are exposed to a range of Islamic viewpoints: the faculty contains Sufis, Salafis, and independent Muslims. Faculty members are highly visible outside the university. In Nigeria, university intellectuals frequently hold civic and government positions. Many scholars from BUK’s Islamic Studies Department advise the federal government or the government of Kano State (for example, one scholar is an adviser on Islamic Finance to Central Bank Governor Sanusi Lamido Sanusi). Others teach in mosques or lecture on the radio.

BUK has over 20,000 students, but I do not have a reliable total for students in the Department of Islamic Studies. I am not aware of any cases where the Department refused a Shi’ite or non-Muslim student entry, but as far as I could tell all of the students were Sunni Muslims. The Department attracts some students from outside Nigeria. I met one man from Timbuktu pursuing his M.A. at BUK.

Undergraduates study foundational Islamic subjects (Qur’an, hadith, jurisprudence, etc.). Many students help translate hadith from Arabic to Hausa, one of the Department’s major projects. B.A. and M.A. theses and doctoral dissertations focus on various subjects, but several themes predominate: scholarship on the actions and writings of Sheikh Uthman dan Fodio (1754-1817), a Muslim scholar who established the empire of Sokoto in present-day Northern Nigeria in the early nineteenth century (many students also write about dan Fodio’s contemporaries and successors); studies of contemporary problems in Nigerian Muslim society, such as divorce; and analyses of Islamic scriptures and classical Islamic scholarship.

Graduates of Islamic Studies Departments typically pursue careers as teachers (for example in an Islamiyya school), in the judicial system (as shari’a judges, clerks, etc.), or as religious leaders (as imams, preachers, etc.). If one follows the academic path it can lead to a position with the faculty, although competition to reach the doctoral level is intense. The growth of Islamic Finance or non-interest banking in Nigeria may expand career opportunities for Islamic Studies graduates. BUK plans to establish a center for the study of Islamic Finance.

Less than 10% of Nigerians hold university degrees (my estimate), and many Muslim leaders in Northern Nigeria have not attended university. But in government, education, and even business sectors that affect Muslim life, I frequently encountered officeholders who had at least a B.A. A university degree can enhance a religious leader’s prestige, representing perseverance, certified knowledge, and elite status. In the coming years, one indicator of the importance of university credentials will be judicial appointments: one professor told me that most judges now do not have university degrees, but that may change as the number of degree-holders with specializations in Islamic Studies grows.

Coda: Boko Haram and the University

In the early 2000s, the Northern Nigerian rebel movement Boko Haram, whose name is often translated “Western education is (Islamically) forbidden,” began rejecting Western-style education for Muslims and forbidding Muslims from working for secular governments. The movement’s founder, Muhammad Yusuf, fell out with his former teacher, Sheikh Ja’far Mahmud Adam when the latter, a university-educated man, tried to dissuade Yusuf from his hardline positions.

Now both Yusuf (killed in police custody in 2009) and Sheikh Ja’far (assassinated by unknown gunmen, possibly from Boko Haram, in 2007) are dead, and Boko Haram is attacking schools in Northern Nigeria. Boko Haram has not specifically targeted Islamic Studies Departments or faculty, but neither has it exempted universities that offer Islamic Studies from its campaign of violence. Violence in Maiduguri, the epicenter of Boko Haram’s activities, forced the longtime closure of the University there, which has a Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies. Boko Haram attacked a Christian worship service at BUK in April. The debate between Yusuf and Sheikh Ja’far, it seems, is not only not over, it is also playing out with bullets and bombs.

Alex Thurston is a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Northwestern University. For 2011-2012, he is conducting dissertation fieldwork in Northern Nigeria. Alex has written for the Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, and The Guardian. He blogs at http://sahelblog.wordpress.com. Read Alex’s previous posts on religion in Nigeria and the Sahel region here.

With support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion and International Affairs.